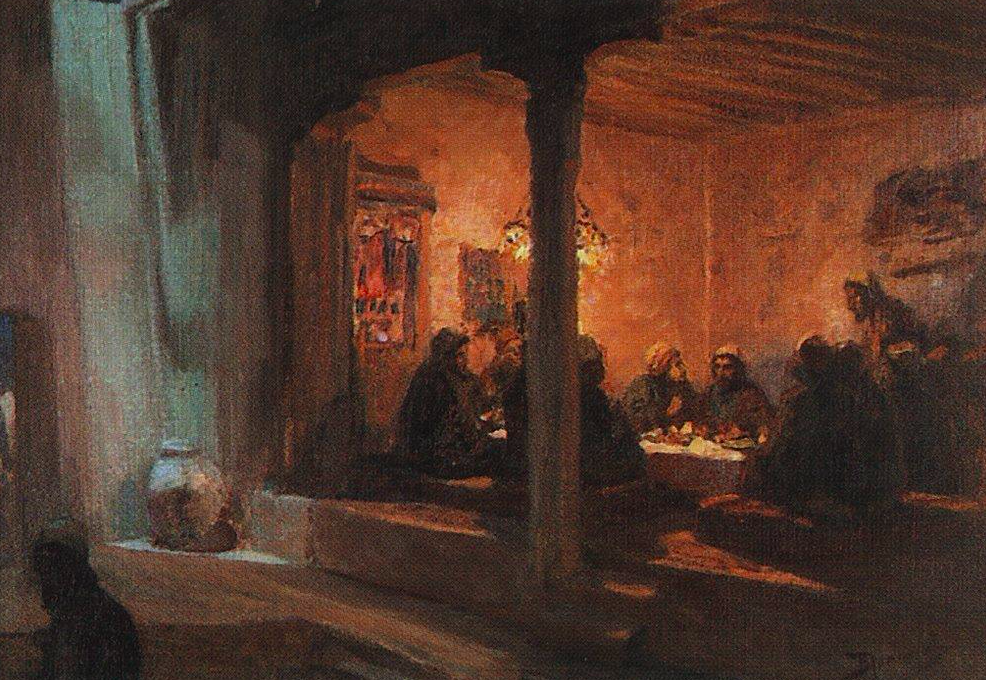

There are so many grand and wonderful paintings of early church times of table fellowship. And some I really, truly like. Yet, there is a male-centerness to them that would not have reflected the actual tables of Christian fellowship of the early church that these scenes are to depict. I do not see women and wives and slaves and children; typically just men, and when women are depicted, they are serving food. Most of these grand paintings were created and come at the time after Constantine, the Roman Empire Caesar (272 AD - 337 AD), herded the churches away from the homes of Christians and into buildings sanctioned by the State, along with laws to build up and protect an appointed church authority and priesthood consisting solely of men. Church began to reflect the culture of the empire more so than the one painted by the Apostolic church and the early church through 300 AD. This move recreated church away from the Table fellowship of strangers and unequals that had increased and spread since the days after the Pentecost of Acts 2. Most of these wonderful paintings, as far as I can tell, come from the post-constantine Christian era, reading their “church experience” back into the apostolic and early church (form and experience). We do that, too, now. We start with how we do church now and read it back into the New Testament accounts and teaching--this anachronistic. Our vision of the church not only reflects the flaws and the unredeemed aspects of our social and cultural times (and trends), but we read this experience of church back into the life of the early church and, worse, back into the vision of the church depicted by our New Testament writers. We need to do better.

0 Comments

The goal of redemptive history is the cosmic restoration of creation. This is the story of the Bible. This is the church’s story. This should be your church's story. God has determined to use a redeemed people to herald this message. The ekklesia of Jesus, the gathered-church, composed of redeemed and restored people, living out the gospel, illustrating this cosmic restoration through its treasonous worship of the risen Jesus, the Lord over all other claims to the throne, its missional behavior to its neighbors, and , particularly, through the fellowship of restored human relationships among strangers and unequals. The gathered-church of the Lamb of God is unlike any and all other rebellions and resistance movements: church is not (ever) aligned with a government or party or state or king in order to violently overthrow or by means of State-authority and any form of violence to maintain; church is never (ever) aligned with the spilling of blood through strength or cunning to change or maintain the status quo of an unredeemed social structure or cultural state of affairs; and, where privileged to participate, church does not count on the ballot-box to overthrow power or maintain a particular person or party in power. The church uses a table of fellowship over food, broken bread, and a raised cup of allegiance to the risen King of kings and Lord of lords, now seated at the right hand of God in the heavenly places. This has been and is God’s way of, not saving the State or some preferred demographic or cultural value, but demonstrating that all of history is moving toward His ultimate conclusion of a restored creation. How does God reveal and accomplish this purpose of history? Little and grand tables, scattered throughout time and place, some well noticed and many hidden in the back alleys and among the margins–this has been where God does his rewriting of corrupted history and the deconstructing of the powers of humankind. This is church-story. Not just the best story. But the true story of history. This is the story you and I are invited into; and, the gathered-church is the place God restores all things. Not the battlefield. Not the ballot box. But at tables of strangers and unequals.

In 12 days many of us will be voting. I certainly encourage voting for a host of reasons (despite the feeling that nothing really changes anymore after we vote), but this annual trek to the polls teaches something to Christians (i.e., the habit, the liturgy of voting teaches something) and forces Christians and churches to focus on electoral politics as our (i.e., the right, left, conservative, progressive, libertarian, independent)–as our weapon of choice to bring change or to simply protect what we have so it isn't taken away. I don't like this about our politics, that is, for what it does to the church (rather, to churches) and how it makes us as Christians think this is the means we (or God) accomplishes change. Yet, think of the early church. I find, streaming from the pages of the New Testament (I believe), God's means to affect change was to personally (face-to-face, person-to-person) strengthen the weak ties among people at the table, who had never sat for a meal together before . . . strangers and unequals celebrating the Lord’s Supper, the breaking of the bread, a meal, and the lifting of a cup to remember Jesus’ death and resurrection. This table intimacy among differing, adverse, conflicting, socially unacceptable levels and classes of society met as family–where neither slave nor free, neither male nor female, neither clean nor unclean actually meant something huge and not a cliché. This is where change happened. And, it most certainly did. Unheard of change at the deepest societal levels and in the nooks and crannies of both the back alleys and in the palaces. A place where “one in Christ” carried significant social and cultural changing power. Of course I will vote on November 6th. But frankly not much will change. But what I do know that would (that will) bring about change, especially change in my community and for my neighbors, is my church, as we seek to make that table (and what it does to our actual, interactive, on the ground fellowship) a table of unequals and strangers “one in Christ.” Where in the wider community, now a gathered-church, weak ties between people need to exist to changes lives, to prosper communities, and to strengthen neighborhoods. That is how it was done post-pentecost and for the amazing first 150 to 300 years before Caesar put us in a box. Time to get out of that box. Remember we commit treason (or we should be) every time we lift that cup to remember Jesus, to proclaim his death, until he comes again.

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (B) Baptisms. Samaritan “men and women,” an Ethiopian eunuch, the oppressing-Christian-killing Saul, a military Gentile, a Gentile (single?) woman (and “her household”), a Gentile jailor (and “his household”), and an outlier, Corinthian Jew with a Gentile name, Crispus (and “all of his household”) are Luke’s narrative choices of “baptism” stories. Of course, there are multitudes more, but when Luke has a chance to write about baptisms, these are the ones he chose for us to know. In fact, the first time he mentions anyone being baptized after the initial Pentecost events, it is Samaritan “men and women” (8:9; 12).[1] And, the first time Luke tells of an individual that is baptized, it is a foreign eunuch, serving a pagan king (8:36–8). What are Luke’s narrative choices embedded in the “church” story telling us about “church”? The baptism habitus of the gathered-church amid the deipnon (Lord’s Supper) moved people of unequal social status into being “one in Christ” as individuals and as households (which included women, children, and slaves) amid intimacy, reclining among unequals, the risk of being seen as a treasonous gathering (for at a deipnon there were on-lookers), celebrating the death of a traitor acknowledged as Lord and Head of the new social group. Household baptism (along with Luke’s other narrative choices) displayed the counter-cultural and, thus, seditious nature of a gathered-church. This is further seen in NT cross-related texts, that is, trajectory application regarding the unequal “mix” of who made up the gathered-church. Paul links the reconciliation of Jews and Gentiles as a trajectory application of the cross: But now in Christ Jesus you who formerly were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For He Himself is our peace, who made both groups into one and broke down the barrier of the dividing wall, by abolishing in His flesh the enmity, which is the Law of commandments contained in ordinances, so that in Himself He might make the two into one new man, thus establishing peace, and might reconcile them both in one body to God through the cross, by it having put to death the enmity (Eph 2:13–16). This reconciliation, wherein “the both” are created “one new humanity” (v. 15c),[2] is directly related to the nature of the church: “the both” are fellow citizens of God’s household that is growing into a holy temple in the Lord, being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit (vv. 19–22). The unequal-oneness is the trajectory application of the death of Jesus. Later, Paul calls the church to unity through the imagery of its “one baptism” (4:5). Paul associates baptism with Christ’s death: Or do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus have been baptized into His death? (Rom 6:3).[3] This is important, for Paul, then, links baptism to the nature of the gathered-church. The Colossian believers, Paul writes, have been buried with Christ “in baptism” (2:12a) and as a result, they are to set their minds on things above where Christ is seated at the right hand of God (3:1). This is directly related to the Colossian gathered-church’s identity: Do not lie to one another since the old man is laid aside with its practices and the new [man] is put on that is being renewed into the image according to the one who created it, where no Greek and Jew is, that is (kai) [where there is no] circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, freeman, but all things and in all is Messiah [my translation] (3:9-11). The setting is most certainly the deipnon (cf. 3:12–16) and the letter itself most assuredly was read at the after-meal symposium. Furthermore, in other passages Paul links baptism habitus to the associations within the gathered-church: For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:13). The gathered-church exists where unequals are present (and welcome) and there is no ethno-centric center of power. Furthermore, this cross/baptism-nature of church is applied to the gathered-church in Corinth regarding the Lord’s Supper and offers more support for a better reading of the Corinthian “table” issue (1 Cor 11). Paul links their baptism as a sign of their oneness (i.e., one body, 1 Cor 12:13a) and, then made trajectory application of whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (v. 13b) to the issues experienced at the meal/table (i.e., the deipnon). Participation in the Lord’s Supper (the habitus) is itself to be proclamation of Messiah’s death (v. 26, For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until He comes), but was not so in the divisions made at the deipnon food habitus: . . . when gathering together as church, I hear that divisions exist among you . . . Therefore when gathering together, it is not to eat the Lord’s Supper [deipnon] (vv. 18, 20; my translation). [1] My italics to emphasize the inclusion of Samaritan (which is itself impacting) women being baptized. [2] NIV (2011). [3] See Rom 6:4: We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (A) Doing “church” (and all its accompanying habitus) is a hermeneutic for reading the NT and for making church related application. Herein is our hermeneutical problem: NT documents tend to be read (heard) divorced from the most likely venue wherein they were originally read, heard, and repeated as instruction, that is, at a symposium after a gathered-church had reclined at a household deipnon (supper). NT documents should be read within such an authentic venue-hermeneutic, that is as a gathered-church set at a common meal (this is My body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of Me), the lifting of a cup to celebrate the Lord Jesus (this cup is the new covenant in My blood), and the ensuing symposium where instruction would have occurred. There is significant hermeneutical and interpretive value to the household-venue and, as such, is important for faithful and relevant trajectory application. A Meal and Table of Unequals. As most experience the Lord’s Supper, we find no NT equivalent nor within the first 150 years of church history. Despite the NT calling it a supper, most contemporary forms are foreign to the NT, that is, small crackers and a thimble-sized plastic cup (i.e., tokens of bread and wine), with congregants sitting in theater-like rows (i.e., pews or chairs), and all the action and authority “up-front.” The NT Lord’s Supper habitus centered on who reclined at table; whereas, most modern Lord’s Supper habitus is about the appropriate distribution of the tokens. Something happened at those NT/early church gatherings that was culturally subversive and sociologically seditious. The gathered-church formed its identity within the context of “household” amid habitus that was instructive to them and hermeneutical to us. In the Greco-Roman world, food occasions were a means for creating community and bonding that community together—meals were encoded, social habits were established, and status defined.[1] The habitus of each meal-gathering was a message “about different degrees of hierarchy, inclusion, exclusion, boundaries, and transactions across boundaries.”[2] Men were at the center of such meals and where one reclined at table indicated one’s ranking in society and among his associates. Invitation only. Women and slaves served and did not recline at table. Children were not permitted. However, it was acceptable at these meals for entertainment to include sexual encounters “between adult men and pubescent or adolescent boys.”[3] Depending on social class and wealth, there would have been plentiful entertainment, namely “flute girls, party games, gambling, dramas, mimes, strippers, jesters, moral poems, talks, debate, political, religious, moral, abusive, to erotic discussions”[4] and “sexual liaisons and promiscuities were very common.”[5] Classes did not ordinarily mix. The household banquet-meal was a built-in means for social formation, “a miniature reproduction of Roman society,” serving as a virtual classroom where one’s social status was taught, practiced, and formally enculturated. Social mapping was practiced, a habitus marking identity and social boundaries. The banquet-meal was the imperial instrument for maintaining “social control of the polis”[6] and was utilized “to dominate people and keep them in their place.”[7] This was interrupted by the household gathered-church where women, children, slaves, and men from differing classes and economic status were welcome to recline at table as equals—literally an open table of unequals. The gathered-church adapted, from its NT origin and as the early church took root in the ensuing century, the customary “pattern found throughout their world,”[8] the Greco-Roman household banquet-meal (deipnon) and symposium. Greco-Roman banquet-meal hosts and guests all acknowledged “the gift of food to the gods,” who were understood as the real hosts of the meal.[9] Such meal-gatherings always honored Caesar and some patron deity, which made such meals a blend of social and religious habitus. However, while Romans lifted a cup to Caesar and national deities, local gods, or a household emulate at the bridge between deipnon and symposium, Christians raised “the cup of blessing” in honor of Christ (1 Cor 10:16; cf. 11:23–28). This made each gathered-church at table seditious, for it was not only affirming a traitorous allegiance to another Lord and God, the occasion created a habitus that taught and maintained new identities, removed boundaries, and promoted counter- and cross-cultural relationships. However, the nature of the gospel and trajectory application of the cross brought about a challenging social-mapping: an ecclesial-demographical mapping of unequal people outside the banquet hall, yet who reclined as equals at table. Adapting the Greco-Roman evening deipnon/symposium set a household gathered-church on the eve (i.e., Saturday evening) of the Lord’s Day (i.e., Sunday), which accommodated the poor and slaves and working children that could not have attended an early morning “service,” for history had yet not giving us a 6-day work week with Sunday off.[10] The wealthy and upper-class church attenders had more power to adjust their daily schedule; the poor and destitute could not. Furthermore, this history and a household-venue hermeneutic allows a fair reading of the deipnon-table and Lord’s Supper issue in 1 Corinthians 10-11 to be about “haves” that were separating (or distinguishing) themselves through food habitus from the “have nots” at the Lord’s table. In this way, the gathered-church-temple (1 Cor 3:16–17; cf. Eph 2:18-22) was being destroyed (1 Cor 11:18–22). These meal-occasions failed, literally at table, to display love toward one another (the reason for chapter 13), thus they had ceased to eat the “Lord’s’ Supper,” abandoning the gospel-ecclesial social-mapping and habitus purpose of the meal.[11] [1] Lanuwabang Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement in Fellowship Meals: The Socio-historical Background of 1 Corinthians 11:17–34 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2016), 3; quoting Robertson Smith from his Religion of the Semites (page 217); —eating was understood as a sacred, mystical act when done together [2] Mary Douglas, “Deciphering a Meal,” in Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology (London: Routledge, 1975), 249–75, 249. [3] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 17; less so among Jewish households, but still drinking and other forms of merriment were very central to the latter, symposia, part of the banquet. [4] Ibid, 16. [5] Ibid, 17. [6] Street, Subversive Meals, 9. Italics original. [7] Ibid, 15. [8] Street, Subversive Meals, 11. [9] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 15. [10] Ferment, 191; note: Justin, 1 Apol. 67.3; Origen, Hom. Luc. 38.6 [11] Street, Subversive Meals, 37; a similar venue-hermeneutic reading can be made of the James 2 “church” text. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

This is a fair contextual, occasional, and exegetical (perhaps even original and certainly possible) reading of the Philippians 4:6-7. First, I have taken mēden (“no one,” μηδὲν) as nominative (vocative, actually), that is, as the subject of the command, which is totally possible and perhaps even preferable, and not accusative (i.e., what to be anxious about, that is no-thing). Granted, virtually no Bible translation or commentator takes the word as nominative. But understand, this word is spelt the same in both the nominative and the accusative declension. Of course, I am still comfortable (exegetically) taking it as the content of what to be anxious about, that is be anxious about “no-thing” ( i.e., mēden, μηδὲν, as accusative meaning, “nothing”)—this is the way Paul is normally translated (lit, be anxious about nothing, or as the ESV has it, “Do not be anxious about anything”). Yet my rendering (which is completely possible) is fair and fits the gathered church occasion and context, that is a church gathered at an evening banquet-meal, time of worship, and instruction) in some believer's living room in Philippi. I read our letters from Paul a little differently now that I have better understanding what the worship setting and venue looked like at that time. Each of Paul's letters, most likely, would have been read at a local church’s worship-time, most likely on a Saturday evening (it would be almost 150 years before churches started meeting early Sunday mornings on a regular bases) in someone’s home (i.e., a house-church). We know the patterns, that is the setting—what it looked like. The early church would gather together for a full meal (i.e., a supper), worship, and instruction patterned after the banquet-meal-symposium that were common to groups, societies, cults, guilds, and paterfamilias (male head of households) throwing a banquet at his home throughout the Greco-Roman world. At these banquet-meal-symposia, where the host would celebrate and drink (lift and pour out) a cup of wine to Caesar and some god (small “g”), or at the honoring of some benefactor, the new church would gather locally to celebrate and drink (lift) a cup of wine to celebrate and remember the Lord Jesus Christ. Most certainly this explains the first command in the text: “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, rejoice” (v. 4). The banquet-meal-symposium of a local gathered church would break bread at the beginning (marking the start of the worship and fellowship time) as Jesus did with his first disciples at the Last Supper. Then, they would share a meal together. At the end of this time, the host would raise a cup of wine to celebrate and remember the Lord Jesus Christ (which normally in a non church setting would have been toasted to caesar and/or a god or at least their house-hold god). Then, the host would he would welcome communal prayers of the guests and, then, there would be a lively time for apostolic instruction and teaching of the gospel (which was the symposium). If there was a letter from, say the Apostle Paul, it would have been most likely read (and discussed) at this time. So re-imagine Philippians 4:4-7 being read out loud (obviously with the rest of the letter) at the just celebrated Table of the Lord (i.e., the lifting of the cup). Now hear the nuances of this setting, fellowship, and instruction. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, rejoice. Let your spacious generosity and humbleness [my rendering of the word, "gentleness," or "reasonableness" in the text] be known by all (who are at the Table of the Lord in the midst of your gathering together for worship [which fits the reason of the Letter in the first place, to heal conceited division and bring about joyous unity]. The Lord is near [a perfect phrase to mark the lifting of the cup and remembering the Lord and His kingdom have come]. No one (at the table, celebrating the Lord’s Supper at worship) be anxious. But! In all things by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving, your requests, make them known to God; and, the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.” The power of this reading can be felt. May it be so in your own gathering of the saints.

“For this reason many among you are weak and sick, and a number sleep” (1 Corinthians 11:30). Many, if not most, come to this verse (v. 30) in the 1 Corinthian 11 version of the Lord’s Supper written by Paul to the church at Corinth (11:23-32), and with little or no exegetical or contextual consideration, nor historical examination, take the “weak and sick” and “a number sleep” to mean the “unworthy” (v. 27) who had partaken of the Eucharist. In other words, they, then, had received some form of judgment (i.e., becoming weak, sick, and worse, die). More specifically, many also take these as non-Christians that have eaten the Lord’s Supper in an unworthy manner. This reading is also used as a rationale to discourage nonbelievers from partaking in the Lord’s Supper during a worship service each week. There is, however, a better, and more likely, reading of this important text. 1) The reference to “sleep” is a biblical euphuism for Christians that have died, not unbelievers—so, this verse is not a proof-text for non-believers who have “wrongly” partaken of the Eucharist. It is believers who have fallen asleep (died). And as far as I can tell, there is no exegetical reason the "weak," "sick," and the sleeping must be "the unworthy" of verse twenty-seven. Additionally, the term “weak” in Paul’s 1 Corinthian context also, usage-wise, points to believers. (See #3 for whom those who are the "weak," "sick," and asleep are within the Letter context and social location.) 2) The “meal” was a central element in the apostolic church gatherings and was so in the early church period for about 150 years after Pentecost (and continued in some form for another 150 years through about 300 AD). 3) There is a likely famine (or period of severe food scarcity; e.g., Suetonius, Claud. 18.2; Josephus, Ant. 3.320-21) that researchers have discovered or recognized had occurred at the time in the surrounding area, which would have made the meal issue a central concern (especially, if the poor in the congregation was not even finding food for themselves “at church,” let alone on the marketplace). 4) The occasion of the Letter itself is instructive, namely there is an elite-ism (which affirms the Roman social structure and association or social etiquette) that found its way to the meal or banquet component of the church gathering, which would have occurred just prior to the sharing of the cup of remembrance (of the Lord Jesus’ death) and the symposia or instruction time. 5) Verse 33 ought not be ignored in that it directly suggests that some were not allowed or welcomed or accepted or or re-classified to a different "spot" at the meal or simply shoved out of the meal (demonstrating the etiquette of the Empire and not the etiquette of the Kingdom of God). The primary instruction is, not to end the meal component of the gathering, but to wait for all to eat (v. 33) and thus reflect the social etiquette of the gospel. Plus, it is to those who eat before or at the expense of the poorer, less socially acceptable Christians that are told to eat at home (v. 34); still no instruction to end the meal/banquet as a form of the church's gathering for worship, instruction, and fellowship. Non-Christians are not in the purview for the correction and admonition here, but the Christian elites and status seekers. A more likely reading of verse 30 (For this reason many among you are weak and sick, and a number sleep) is that the “weak,” “sick,” and the sleeping (i.e., the dead) are, not non-Christians, but the poor and less acceptable Christians of the church at Corinth. There were those in the congregation who were sick and some had passed away (possibly) as a result of the famine, which was only made worse by the pushy elite Christians who stormed the meal ahead of or in spite of the poorer, less socially acceptable members of the body of Christ. If not as a result, then most certainly the reference to the weak, sick, and sleeping are a kingdom-reminder of why table fellowship was of such importance (the poor and marginal received a form a assistance, i.e., in this case food). The fellowship meal in the Corinthian form was not affirming the gospel. This is what Paul is addressing.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed