The mission summary frames the Mark 3 commission My syntactical conclusion developed above—the authority to cast out the demons (3:15) is the content of to preach (v. 14c)—is made more evident by the Mark 3 commission’s link to the Mark 1:14–15 mission summary: “Now after John had been taken into custody, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God, and saying, ‘The time has been fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe in the gospel.’”[1] The geographic identifier--Jesus came into Galilee (1:14b)—indicates that these two verses form a summary for the Galilean ministry that runs from the fisher-promise--And He was going along the Sea of Galilee . . . Jesus said to them, “Come follow (after) Me and I will create you to become fishers . . . ” (1:16–17, author’s translation)—through 9:33–49, a teaching episode set in the Galilean town of Capernaum (9:33).[2] These geographic bookends focus the mission summary at a literary level on Jesus’ Galilean ministry, forming an underlying relationship between “preaching the gospel of God” (1:14c) and Jesus’ teaching and actions emplotted throughout the narrative. Furthermore, the central role of Jesus’ casting-ministry is also clearly established by a casting-event bracket, first at the opening of the Galilean ministry (1:21–27) and, then, at the close (9:38–41) as Jesus begins turning his attention toward Jerusalem and the soon approaching passion. This bracketing affirms the importance of “casting” activities in the Galilean section of the Gospel narrative: the first time Jesus “came preaching the gospel of God” (1:14c) in Galilee involved an exorcism (1:21–28) and at the close of the Galilean ministry even those outside the inner-circle, who acted out the mission of Jesus, are associated with “casting” (9:38–41). Mark 1:14–15 is clearly a summary and it functions as a programmatic and interpretative lens for his Gospel narrative and for the ministry of Jesus that was carried out through both teaching and miracle that reveal the nature and significance of the kingdom that has come near (1:15). The content of the gospel of God (v.14c) is epexegetically explained in 1:15.[3] The gospel that has come from God (1:14c)[4] is defined by each element in verse 15, clarifying God’s decisive action in the appearance of his Son.[5] The mission summary is composed of two parts: first, an indication that Jesus had preached “the gospel of God” (v. 14); then, the content of that preaching (v. 15). The Mark 3 commission follows the same pattern set by Mark 1:14–15.

The gospel of God (1:14–15) and the Mark 3 commission both are announcement in which the content is the arrival of the kingdom of God and, as well, its implications. The content of the gospel of God (1:14) that Jesus preached is summarized in declarations (v. 15) that Mark has carefully balanced, forming two pairs of statements “each constructed in synthetic parallelism.”[7]

The first pair are declarative statements, each containing a perfect indicative verb that implies a completed action that continues in effect; the second are present imperatives—commands—that flow from the declarations. The first indicative is the time has been fulfilled, which corresponds to the first imperative “repent.” The second indicative is the kingdom of God has come near, which corresponds to the second imperative “believe.” The meaning is rather straightforward: the time of the old age has been completed (cf. this present evil age, Gal 1:4), that is, the time under Satan’s dominion has come to its eschatological end; and, the time of God’s kingdom has now been inaugurated, reorienting the realms of humankind to reflect his right to reign and rule.[9] The pattern established in 1:14–15 is exactly what happens throughout the Galilean ministry and is reflected in the Mark 3 commission. Timing and the evangelistic task of fisher-followers The question of timing is relevant, for the summary (Mark 1:14–15) informs us that both the time has been fulfilled and the kingdom of God has come near (author’s translation). Discussions regarding the “time” fulfilled and the “nearness” of the kingdom typically focus on chronology: do these references indicate present or future events? Mark, however, uses the word kairos (time) to indicate a decisive moment (12:2; 13:33) or a span of current time (i.e., a season; 10:30; 11:13). Mark’s use of near (eggizo centers on proximity (11:1; 14:42). These are significant observations, for at the literary level, Mark’s narrative portrait of Jesus’ “preaching of the Gospel of God” (1:14c) and its content (v. 15) parallel his immediate and proximate actions during the Galilean ministry: the end of Satan’s dominion and the inaugural reign of God are demonstrated in Jesus’ authority to cast out demons and through his other miracles as well. A number of interrelated events follow the mission summary that stress arrival (i.e., the kingdom has come near). This is a function of the following miracle stories, particularly the casting, that demonstrate “God’s rule had entered into history.”[10] The weight of the narrative parts (i.e., the episodes, stories, and events throughout the narrative) indicates the timing is immediate in Jesus’ ministry and, then, will continue through the authority to cast granted to the fisher-followers (3:15; 6:7), who are commissioned to imitate Jesus’ mission. This fits the use of the perfect indicative verbal expressions in the mission summary (peplerotai, has been fulfilled; eggiken, has come near), the subsequent narrative (i.e., the Galilean ministry), and the Mark 3 commission. The kingdom of God is the substance of the created fisher-followers’ evangelistic activities, not solely as proclamation, but primarily their actions (i.e., their deeds), which continuously reveal the kingdom’s nearness. Like the word sowed by the Master Sower in the Mark 4 parables and Jesus’ kingdom-deeds (i.e., deed-parables), this, too, is the evangelistic task of fisher-followers. The significance of the Mark 3 commission It is not coincidental that the fisher-promise (1:17) follows the mission summary (1:14–15), for the Mark 3 commission is the inaugural fulfillment of the fisher-promise and echoes the pattern set forth in the mission summary. The “casting” episodes act as indicators that the time has been fulfilled and the kingdom has come near (1:15), for Jesus is already invading Satan’s territory. The role of fisher-followers is to imitate Jesus’ activities: as Jesus was the premier inaugurator of the kingdom of God, thus ending Satan’s dominion, which is demonstrated through casting, so, also, the fisher-followers (3:15). This is the significance of the Mark 3 commission: to be obedient to the commission, then, is to develop authoritative application through analogous deeds that demonstrate the defeat of Satan’s kingdom and that reorient both people and the world toward God’s dominion. The final interpretive summary (III) below gives a sense of this fuller understanding of the Mark 3 commission and its significance for the reader/listener today:

[1] The Mark 1:14–15 text here reflects my translation of the Greek, which will be used throughout the remainder of this section, unless otherwise noted. [2] Although most limit the Galilean ministry to Mark 1–6 (note for example Guelich, Mark 1–8:26, 41; Witherington, Gospel of Mark, 77), it appears that it continues through to Mark 9, which is indicated by the geographic bookends. [3] Guelich, Mark 1–8:26, 43. [4] Regarding the phrase to euaggelion tou theou (the gospel of God, Mark 1:14c), the genitive tou theou (of God, Mark 1:14c) is most likely used ambiguously by Mark to mean both the Gospel about God (objective genitive) and the gospel from God (subjective genitive). Nonetheless, here I indicate that the phrase to mean “the gospel from God” emphasizing God’s action in Christ Jesus, his appearance and ministry (e.g. see France, Gospel of Mark, 91). [5] Lane, Gospel According to Mark, 63–64; Witherington, Gospel of Mark, 77. [6] Along with Mark 1:14–15, the Mark 3:14–15 reference here reflects the author’s translation. [7] Guelich, Mark 1–8:26, 41; also Marcus, Mark 1–8, 175. [8] See Marcus, Mark 1–8, 175; this gird reflects the author’s translation of Mark 1:15. [9] On this I follow Marcus, who has a good discussion on the meaning of the mission summary (Mark 1–8, 173–76). [10] Ibid., 46.

0 Comments

Almost all works on the relationship between evangelism and social action, most books on the church and the poor, and every book out there on the subject of Christians and social justice are argued from experience, a theological bent, a political aisle, or a church experience. Although such platforms have value and have their place, there are few, if any, volumes that seek an exegetical foundation for the author’s conclusion: a what does the text imply? My Wasted Evangelism is an exegetical argument for understanding that social action can be a component of biblical evangelism and ought to be an element in a church’s task of evangelism.

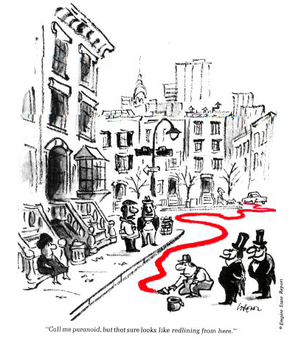

Please consider purchasing a copy of my Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, a deep, exegetical read into the Gospel of Mark. All royalties go to support our church planting in the Hill community of New Haven, CT. The book and its e-formats can be found on Amazon, Barns'n Noble (and most other online book distributors) or directly through the publisher, Wipf & Stock directly. Here are some excepts from each of the chapters: Samples Conclusion: Social Action as Christian Apologetic  Simply, affluent suburbanites, despite a claim to a higher work ethic or a more developed sense of responsibility, didn’t do it on their own; they had help along the way. (I know, many do not like to hear this, but no less truthful.) On the one hand, the non-poor’s social construction of reality, which they now experience as everyday life, allows them to benefit, not just from the market, but also from past actions of government that laid much of the groundwork for continued prosperity. On the other hand, the concentration of poverty in central-cities is not simply about laziness, slothfulness, or even personal sin. (I assume the non-poor who benefit from the current structure and mediating institutions are just as much “sinners” as those living in geographic areas of concentrated poverty.) Indeed, much of what is in place and experienced now as normal arose from various forms of racism and redlining practices, as well as “the concentration of subsidized housing projects” that, as Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck observed in their Suburban Nation, “destabilized and isolated the poor, while federal home-loan programs, targeting new construction exclusively, encouraged the deterioration and abandonment of urban housing.” The fact of poverty and the reality of those affected by it in the central-cities could not have happened any more effectively if it were actually planned and implemented with malice. Without the aid of government policies and subsidies, as well as municipally empowered zoning laws and discriminatory business policies, the foundation for exurban wealth in America might not have happened. Rather than lamenting this inequitable state of affairs, participants, including many non-poor Christians, have been encouraged to rejoice in the “prudence” of such strategies and the institutions, capitalism and the “mythical” market, that sustain them. The modern, non-poor suburban dweller is the heir of such socially constructed forces.

Emil Brunner once remarked, “For every civilization, for every period of history, it is true to say, ‘show me what kind of gods you have, and I will tell you what kind of humanity you possess.’” For the Christian and Christian community it is: Show me what kind of association you have with those living with the effects of poverty, and I will tell you what kind of god you worship. The reality of everyday life is that Suburban life and its enablers—the free market and human acts of power—are often at odds with the gospel, especially a gospel that has been formed by the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition. For the non-poor Christian, this is an idolatrous mode of living and does not offer a biblically defensible apologetic for the God revealed in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 *adapted from chapter 5 of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism

to the confrontation and the seeming ultimate curse of total unforgiveness is all about Jesus vs. Jerusalem temple leadership.  It is interesting that contemporary church leadership typically uses the threat of blasphemy of the Holy Spirit against lay-people who do not surrender to how that leadership understands their own authority and how they perceive God’s will over those very lay-people’s lives. However, church leaders cannot escape the narrative fact that the Mark 3 Beelzebul episode itself, the preceding conflict thread (2:1–3:6), and, as well, the Sower parable (4:1–12) seem specifically directed at them. Jesus uses the convention of shame in the Beelzebul story, pointing to a needed correction within church leadership. For church leaders a posture of shame is needed, which once adopted reminds them of the illusive nature of status, the dangerous allure of power, and the recurring failure of faulty structures to guard the gospel and the church from the destructive influences and seductive cultural patterns that oppose God’s reign over all spheres of humankind. It should not surprise us that the shaming inherent within the Beelzebul episode, intertexted through Mark’s Old Testament links, connects church leaders to the church’s responsibility (and neglect) for the economically vulnerable. Caring, protecting, and advocating for the poor gives away power and public association with those living with the effects of poverty risks lowering one’s church community status. However, maintaining power and its enabling structures so that one’s social standing and status remain in place (even among, and more particularly, the Christian community) at the expense of the weakest and most vulnerable among us is synonymous with blasphemy against the Holy Spirit—breaking covenant, risking outside status and, thus, the condition of being eternally never forgiven. The biography of Jesus vs. Jewish leaders in Mark 1-3 is linked to the biography of the disciples, who like the ones beside Jesus (i.e., his associates and extended family, 3:21; cf. 6:1-6) and like Jesus’ earthly family (3:31–32), are at risk of being outside (6:51–53; 8:16–21; 8:34–38; cf. 9:33–34; 11:31; 16:14), if they, too, are not doers of God’s will (3:33–35). This is particularly relevant to church leaders, as they stand before the Mark 3 text (i.e., the Outsider-Insider sandwich), for the Beelzebul episode ought to shame them in those areas that are too closely identified with that which opposes God’s rule and kingdom (cf. Mark 1:15; 3:25). Mark’s Beelzebul episode functions similar to OT penitential prayers, allowing the reader/listener to enter a life narrative that reflects an appropriate shame for allowing those destructive forces and influences to distract from obedience to God’s word and work in the world. And like OT penitential prayers, a disposition of shame humbles the reader/listener before their “disobedience to the Mosaic ideals” that often reflects “mistreatment of the poor and the weak,” and gives them a way home that maps a spiritual disposition for restoring a fractured obedience to God. Interestingly after confessing that Jesus is the Messiah, Peter is soon rebuked as a surrogate of Satan’s interests: “Get behind Me, Satan; for you are not setting your mind on God’s interests, but man’s” (Mark 8:33). Significant to the reader/listener is the immediate juxtaposition of the Peter-Satan rebuke and Jesus’ admonishment that true followers must deny themselves (the opposite of power, an emptying of power) and take up their cross (v. 34). Church leaders who intentionally incorporate social action in a church’s evangelistic activities fulfill the obedience implications of the Beelzebul episode and, thus, raise Jesus’ honor rating in the public sphere. Without such a public disposition, church leaders are further warned that “whoever is ashamed of me and of my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, of him will the Son of Man also be ashamed when he comes in the glory of his Father with the holy angels” (Mark 8:38).

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed