Many Christian advocates for social justice cry out for deconstructing privilege and the privileged from a platform of privilege themselves, a place of power, celebrity, notoriety, and/or money (not to exclude address, i.e., where they live and the resources at their disposal). Over and over, their advocacy seems to contradict their status and lifestyle. These same advocates for social justice use the Bible (and for the most part I align and, even, agree with much of their message; not so much their means, which are, for the most part, not biblical, but mostly cultural, political, and status resourced). Here’s what strikes me: The original advocacy (i.e., the gospel of Jesus, the Messiah) and how it changed things, how it deconstructed, and, then, reconstructed habits and lives and attitudes did not occur from the place of power, but from the place of powerlessness. We learn this, first, from the humanizing (i.e., incarnation) of the One who was in the form of God from all eternity taking on the form of a slave (Phil 2); and, second, from the small gatherings of believers in homes (living rooms), we now call churches, made up mostly of the poor and powerless in the early decades of the church. Of course, there were some wealthy among them and some who provided homes for churches to gather; yet, here, too, as Christians and people that used their homes for believers to gather would have lost their status and social standing (at least in part), leaving them to be classed among the powerless and the bottom-demographics of the Roman Empire and Greek world. It would be nearly three centuries before the wealthy, educated, and powerful had control over the affairs of the church. No longer in homes. State (i.e., Empire) sanctioned and often constructed buildings became the addressed-venues of churches. Highly trained and Empire sanctioned clergy had authority over the church. No longer food for a supper, but tokens of bread and wine were used and guarded and distributed by this now elite, often cosmopolitan, clergy. Now, the State (or Empire) controlled the advocacy, that is the results of the gospel. The poor and the powerless among the Christians were separated from their more wealthy, educated, and affluent Christian brothers and sisters, by design and by default. Yet, it was not so in the beginning and for about 300 years of church history. Obviously the shift crept in, but was not fully established until the Emperor “converted” (but was not baptized) and the Empire started creating a space of power for the leaders of the church. My concern here is not to dwell on how the church came to know power and has been able to produce power and the powerful, but to highlight that our present social justice advocates do so from a platform of power that the very gods of empire (call it as you will, colonialism, Christendom, American upward mobility—no matter, it is the powers that) has given (such power) to them. Few seem to divest themselves of power and privilege (as did Jesus, whom they say they follow) and take on the form of a slave and being obedient to the point of death, even death (i.e., dying to self) on a cross (again, cf. Phil 2) on which they are called to carry; but, yet, offer, still, their justice rhetoric and (really what is often simply) political vision from a place of culturally designed privilege and power. Until this is recognized (and deconstructed I might add), such advocacy will rely on the power of the State to enforce their vision (no matter how clothed in biblical language it might be). It is my humble opinion that we need to rethink church, especially as the place where systemic change happens, even though it is a place (and the space) of the poor and powerless. (Well, it should be.) Of course, plenty of “churches” need repentance, an attitude of lament, and a call back to the gospel (liberal, progressive, and conservative churches), but, nonetheless, it is, still, the church (local churches) where the alternative of God’s kingdom is to be lived (by believers) and observed (by outsiders). (Not “look how we vote” or “look how we protest”; but “look how we live and fellowship as strangers and unequals, as brothers and sisters in Christ, a wholly new family in Christ.”) The church, a church, local churches scatter from street to street, neighborhood to neighborhood, places where strangers and unequals meet over a meal (break bread) and celebrate (raise a cup) that they have no other Lord than the risen Messiah, who sits at the Father’s right hand (their only source of power, which is lived by denying themselves and taking up a cross). Such advocacy should not rest in individuals who have forms of cultural power at their disposal, but an advocacy that stems from a gathered-household of faith. Social justice advocacy should be a lived-church thing (and for that matter, the place of no power, no culturally derived and given power). Social justice is a lived-church advocacy. Our advocacy for social justice, like any of our boasting (our culturally, socially, and economically derived desires, vision, or means of power), needs solely to be first and foremost “in the Lord” and made from a willing place of foolishness. Our social justice advocacy platform, the place where we are “like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things,” this is the place, Jesus’ church, local churches, find themselves and where authentic social justice advocacy has its gospel platform.

0 Comments

Almost all works on the relationship between evangelism and social action, most books on the church and the poor, and every book out there on the subject of Christians and social justice are argued from experience, a theological bent, a political aisle, or a church experience. Although such platforms have value and have their place, there are few, if any, volumes that seek an exegetical foundation for the author’s conclusion: a what does the text imply? My Wasted Evangelism is an exegetical argument for understanding that social action can be a component of biblical evangelism and ought to be an element in a church’s task of evangelism.

Please consider purchasing a copy of my Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, a deep, exegetical read into the Gospel of Mark. All royalties go to support our church planting in the Hill community of New Haven, CT. The book and its e-formats can be found on Amazon, Barns'n Noble (and most other online book distributors) or directly through the publisher, Wipf & Stock directly. Here are some excepts from each of the chapters: Samples  The basic dictionary definition of social action is “individual or group behavior that involves interaction with other individuals or groups, especially organized action toward social reform.”[1] Within the discipline of sociology the concept is associated with the work of Max Weber, who understood social action in terms of the relationships people have between social structures and the individuals whose actions create them.[2] Acadia University professor Peter Horvath defines social action as “participation in social issues to influence their outcome for the benefit of people and the community” and concludes that “[s]ocial action can, under favorable circumstances, produce actual empowerment, impact, or social change.”[3] Horvath underscores the importance of seeking and implementing necessary change on behalf of others who do not have access to power for needed change. This can be seen within the social service and welfare arena in which the term “social action” is often used simply to mean efforts to improve social conditions or to address the needs of a particular group within a social setting or societal structure. Social action can be understood as attempts to improve human welfare and to develop commitment to each other, advocating for and/or making changes in social structures (whether at the individual, community, or legislative levels) for the betterment of all. Social action, therefore, is principally the means by which one group offers alterative means to an end for another group, taking action or advocating for action to address social issues and community life. Within the context of poverty, social action is not merely charity, alms-giving, or the transfer of wealth. It is actions taken to address relationships between the poor and the non-poor and, as well, the relationship between the poor, the social structures that can cause or promote poverty, and individuals or groups whose actions create those social structures. Social action is, therefore, associated with actions taken by individuals or groups on behalf of others, in particular advocating on behalf of marginalized or powerless individuals or groups whose access to the systems of power are limited or nonexistent.[4] What, then, is evangelistic social action? Throughout the studies in Wasted Evangelism, I frequently reference Mark’s programmatic[5] use of OT contexts regarding the economically vulnerable and the land, particularly contexts that reference Exodus land-laws (e.g., Exod 21–23; Mal 3:1–5; Jer 5:2; 7:9; Amos 4:1–2; etc.), which, for Mark, informs his understanding of the gospel (Mark 1:1–3; note Exod 23:20; Mal 3:1). The Exodus land-laws are operating behind his programmatic theme, informing the reader/listener of the gospel’s content (i.e., what the gospel is and what it means). Land-laws were given to ensure that the economically vulnerable (i.e., the land-less) were full participants in the benefits of living in the land.[6] This supports the importance of considering the poor in relationship to the Christian community’s social context. In light of Mark’s association of the kingdom with the gospel (1:14–15) and the gospel’s programmatic association with the Exodus land-laws, I propose that biblical social action is a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor.[7] Stephen Mott, former Professor of Christian Social Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, points out that the Bible speaks of what is called “social action” in terms of carrying out justice and caring for the needs of the weak. In her book, Social Justice Handbook, Mae Cannon affirms a similar understanding of the biblical concept of social justice: The resources that God provides were made available to his people from the very beginning. Justice is expressed when God’s resources are made available to all humans, which is what God intended. Biblical justice is the scriptural mandate to manifest the kingdom of God on earth by making God’s blessings available to all.[8] As my Wasted Evangelism, that is, the six deep, exegetical studies (i.e., the chapters), affirm, social action is a relevant and legitimate evangelistic activity when it promotes actions and outcomes that demonstrate the inaugural presence of God’s rule and reign over creation. Thus, social action, the advocacy and activities on behalf of the economically vulnerable, should be an intentional component of a church’s task of evangelism. A slightly adapted set of paragraphs from my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism. All royalties received from sales of Wasted Evangelism go to support our church plant in The Hill community of New Haven, CT. Further Wasted Blog on Barriers to discussing biblical, evangelistic social action >> Barriers [1] Social action. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/social action (accessed: May 27, 2013).

[2] Weber, Economy and Society, 1:78; also see Weber’s Theory of Social and Economic Organization for an in-depth understanding of his social theory, which includes his view of social action. [3] Horvath, “ Organization of Social Action,” 221–31; also see Townley et al.,“Performance Measures,” 1045–72. [4] What is being advocated for throughout [my] six studies is biblical social action that addresses the needs of economically vulnerable individuals and families and activities that seek to reduce the causes of poverty. Although [Wasted Evangelism] does not intend to endorse any particular method or specific type of activity for evangelistic social action, I feel compelled to stress the importance of community development models over paternalistic methods of charity or wealth distribution. I am grateful to Doran Wright, pastor of Grace City Church Bridgeport (CT), for recommending to me A Heart for the Community: New Models for Urban and Suburban Ministry (John Fuder and Noel Castellanos, eds.) as a text that underscores the importance of Christian community development for addressing the needs of poor neighborhoods and communities. Also, see Lupton’s Toxic Charity. For a catalog of various social action and anti-poverty related ministries see Mae Elise Cannon’s Social Justice Handbook. [5] By “programmatic” I mean that a concept, phrase, or an event described in the text contains a main theme of Mark’s Gospel, which offers a referent for meaning, definition, and/or content (an internal hermeneutical orientation) that Mark sets forth, assisting his audience to understand more clearly the parts or plotline of the story in view of the whole story. [6] See Brueggemann’s The Land regarding the biblical responsibilities of God’s people to the land and to the land-less (i.e., the economically vulnerable and the poor). [7] See chapter 2, “Wasted Evangelism.” [8] Cannon, Social Justice Handbook, 22.  An article, “To the Poor, Poverty is More Than Material,” posted on the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics's website lifted an excerpt from a multiauthor volume called For the Least of These: A Biblical Answer to Poverty. The lengthy quote comes from Peter Greer's essay, “A Call to Compassionately Move Beyond Charity.” I was impressed by the reflection on how the poor view themselves and it reminded me of Matthew's “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (5:3). So many take Matthew's reference more broadly to mean those who have a good attitutde and recognize their “poverty” before God. You know, individuals who are humble and not arrogant. These interpretors make a difference between Luke's simple “Blessed are you who are poor" (6:20) and Matthew's “poor in spirit.” However, this is a rationalized, poor rich reading of Scripture that basically strips the poor out of “poor in spirit.” The excerpt from Peter Greer's essay gives us a basis for understanding that living in poverty is more than just a material matter and reminds us that the poor are indeed poor in spirit. In the 1990s, World Bank surveyed over sixty thousand of the financially poor throughout the developing world and how they described poverty. The poor did not focus on their material need; rather, they alluded to social and psychological aspects of poverty. Analyzing the study, Brian Fikkert and Steve Corbett of the Chalmers Center for Economic Development said, “Poor people typically talk in terms of shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, and voicelessness.” The study highlights that, by nature, poverty is innately social and psychological . . . In my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, my definition of “social action” takes into consideration that those living with the effects of poverty are subject to systems and structures, that is the powers, that make poverty more than just material. Social action, therefore, is principally the means by which one group offers alterative means to an end for another group, taking action or advocating for action to address social issues and community life. Within the context of poverty, social action is not merely charity, alms-giving, or the transfer of wealth. It is actions taken to address relationships between the poor and the non-poor and, as well, the relationship between the poor, the social structures that can cause or promote poverty, and individuals or groups whose actions create those social structures. Social action is, therefore, associated with actions taken by individuals or groups on behalf of others, in particular advocating on behalf of marginalized or powerless individuals or groups whose access to the systems of power are limited or nonexistent. We must understanding that being poor is more than the lack of something material, but is living with the effects of poverty upon the whole person. This will help temper our judgments about the poor and why they are poor—and perhaps move us as Christians to relocate ourselves into the lives of the poor. This way we will experience and recognize what it is to be “poor in spirit.” Then, we might very will gain insight and appreciate why Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3).

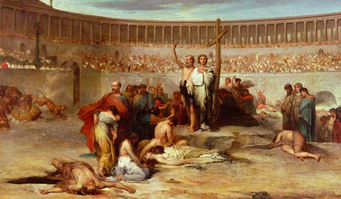

I must make two confessions up front as I began reading through the much treasured, but very often misunderstood John 13 footwashing scene of Jesus and his disciples: First, the eighteen plus years as a planner-grant writer, program developer, and instructor in the social action field, working for agencies that help the poor and low-come, has made me more aware of the Bible’s overwhelming connection to the poor. I most definitely read the Bible differently now. I can see more clearly what I have passed over, spiritualized, and, too often, ignored. I now pick up on nuances in biblical texts and stories that were blurred by my suburban, more privileged up-bringing and how my early Christian years were shaped. I confess am no longer a poor rich reader of the Bible. Second, and with a deep breath, I confess I am burdened and terrified by the call to minister in the Hill community in New Haven, Connecticut. I awake with burdens beyond what I could have imagined as I seek to minister in this broken, yet beautiful community called The Hill. Frankly (and some tell me, don’t let them know how you really feel, don’t show weakness), I am scared to death, sometimes awakening and wondering, “What in the world have I gotten myself and my wife into here?” Scared I’ll mess it up. Frightened that my vulnerabilities will be seen. Afraid my shortcomings, my age, may exhaustion, my weaknesses, and inabilities will be too soon noticed. Yet as Paul heard from God, I too rest in the words, “‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me . . . For when I am weak, then I am strong.” So, with humility I approach the text, weak and a common sinner in the hands of an all-too-gracious heavenly Father . . . and you, with so many reasons to listen to others, but with hopes you will hear the text. Let us pray . . . Let’s time travel back to the first few hundred years of church history. Most of us are familiar with the Greco-Roman colosseums and the brutality of the gladiatorial entertainment in the days of the Roman empire. In those colosseums there was a theater of real, unashamed, and intentional death that was designed to displayed the vertical nature of society, of social order, who had status and who did not—and who was and wasn’t a person. Why do I start here? The arena of death and violence is, you must understand, still the experience of so many around the globe today and in most urban centers in the US and in The Hill community—designed by default and intention, in our very built environment—continues to affirm social vertical status and, dare I say, what we affirm as human. Yet, Jesus and the gospel itself point to a leveling . . . displayed in and through and by the church . . . John 13 will paint this picture for us. Religion in the Roman empire was widespread, huge, and multiple. And yet, no one would have imagined that by the early 4th century Christianity would become a major world religion with adherents numbering among the most significance slice of the empire’s population. But the church didn’t start out that way: the first small congregations had no power, no leverage of status, no influence, and certainly no money. So how? As we read through the early church literature and church fathers, one would look in vain for references specifically to “evangelism” as a verbal witness as a matter of the Christian and church life . . . in fact “speaking” would have probably done nothing and no one would have listened (anyway). Literally in the first few hundred years, Christian literature makes no reference to “evangelists” and or even “missionaries.” So, how? Back to the arena games, say around AD 203: The colosseum-amphitheater was a wonder of Roman engineering. Everything about the architecture and the events were to show off the vertical nature of life and social standing in the Empire . . . vertical . . . higher sections . . . seated by wealth and influence . . . how the stands were filled . . . the upper sections were the visual center . . . magistrates, landowners, benefactors, the elite . . . the entertainment of the populace to bolster status and prestige—all affirming the vertical values of society and civil life. All the while, who were in the death-pits, the forced entertainment of death at the bottom of the arena? Of course the gladiators and lions, but it was the bottom of society that faced death—criminals, the unwanted, slaves, the abandoned—all for sport and entertainment. There we also find small bands of Christians . . . but they faced death (face the beasts and gladiators) differently; their presence in the arena subtly subverted the carefully choreographed vertical event. The masses saw husbands (the paterfamilias, head of households), wives, slaves, doctors, former prostitutes, unwanted children standing together . . . expressing publically right there in the arena Christian horizontality. (Yes, that is a word.) When one would fall, the others would help them up to face death standing. They did not defend themselves in any way. Although the whole of the gospel and NT teaching is behind their behavior, but it is the fact that Jesus left a footwashing community and not a militia or even an academy to invade this world IS THE HOW Christianity grew to overtake an empire. Here in John 13 we have a portrait, along with Jesus’s words, a powerful image and reminder of what the Christian community is to look like in the private habits of our worship and out in the public, in Caesar’s arena of death. The cliché is an easy one: Jesus had to leave, but he left a community. The harder thing: John leaves a community of footwashers to show his love to a watching public world: Jesus’ presence in the world is displayed by a mutually loving church that demonstrates the leveling of humanity, the horizontality of God’s love. Our focus is John 13:33–35—and how these verses stand in the midst of the footwashing scene, surrounded by a traitor among them (Judas) and Peter’s brash, impatient display of allegiance. Little children, yet a little while I am with you. You will seek me, and just as I said to the Jews, so now I also say to you, ‘Where I am going you cannot come.’ A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another: just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another. By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:33–35). Everything seems driven by these words from our Lord, here in chapter 13 and all through John 13-17. So we will center on these verses through the footwashing and the outer bookends texts about Judas and Peter in John’s narrative. I. Setting the stage with the footwashing example–Jesus prepares his new community for his departure II. The juxtaposition: The Traitor (Judas) and Brash, Impatient Denier (Peter) III. The power and habits of our text: The Presence of Jesus is the loving-one-another church–the visible, tangible leveling power of the gospel For the full sermon text, please click the download file below . . .

An etymologically based proclamation-centered evangelism is insufficient to reflect the reality of the presence of the kingdom of God, and, as well, disconnects evangelism, not only from the full life of the church, but also from the public and social implications of the kingdom. True, it might be anachronistically incorrect to jump completely from Jesus’ deeds straight to social action, but it is equally wrong to turn Jesus’ parables into mythic stories that affirm “traditional” American values, limited government, and a political and legal agenda that seeks to promote “our way of life” [note A]. Although leaping from the text to “Christian humanitarianism” is an over-simplification, we cannot ignore that Jesus engaged social institutions, nor overlook that Jesus had immense theological conflicts with temple leadership that reached back to Exodus stipulations and their social implications regarding the vulnerable. The kingdom context places evangelism directly in the midst of the public realm where the Christian community is obligated to deal with structural sin and be an advocate for the vulnerable and the poor. Also, to not include social action outcomes in evangelistic activities, limits the possible outcomes where God’s rule and reign can be expressed, realized, and experienced. Such limiting is the result of a privatized and dualistic understanding of the gospel. Rather, a kingdom-centered evangelism allows for the fullness of the gospel to be realized in individuals, groups, structures, systems, and even culture. Evangelistic strategies and actions ought to enact, demonstrate, fulfill, and advocate for outcomes consistent with God’s reign over all the realms of humanity. Evangelistic outcomes ought to include both personal decisions for Christ and actions that promote God’s righteousness and, in particular, social action that engages the needs and welfare of the vulnerable and the poor. Almost four decades ago, David Moberg, in his The Great Reversal: Evangelism and Social Concern, asked how Christians were to deal with the issues of poverty. This continues to be a pertinent question for the Christian community today—let the debate be lively! However, the topic should not be shrunk to public vs. private, government vs. church, or red vs. blue politics. The gospel of the kingdom is “multidimensional and all-encompassing” and is concerned with both the individual and society. Of course, the gospel calls individuals to a right relationship with God, but it goes beyond private piety, calling Christians, especially Christian leadership, to engage, not only with direct action (i.e., social action) on behalf of the economically vulnerable, but also social and institutional structures that work against fulfilling the church’s obligations toward the poor. The Exodus land-laws, operating behind Mark’s programmatic theme, were given to ensure that the vulnerable (i.e., the land-less) were full participants in the benefits of living in the land.[2] Social Action is a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor. The parable of the Sower who sows encourages the Christian community to waste its seed, sowing it into every realm and every corner of society “in hopes that good soil might somewhere be found,” because it is “our area.” Note A: Actually, it is not altogether inappropriate to make a logical leap from Jesus’ deeds—miracles, exorcisms, healing, over-turning temple-trading tables, cursing a fig-tree, and the ultimate temple-destruction announcement—for it has been noted that some of the miracle stories contain references to actual political referents, and the miracles themselves carry a contrast to a social-political dynamic of crowd control. Note B: For insight on “the land” and the land-less poor, see Walter Brueggemann, Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith (Fortress). *Excerpt from the 2nd chapter of Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism (Resource Publications, an imprint of Wipf & Stock).

Biblical social action that reflects advocacy on behalf of the poor--gets your hands dirty and messy9/24/2015  For the church to have a public voice that affects the public square with kingdom values, it needs to have public actions that demonstrate the interests of the community and, in particular, actions that reflect advocacy and social action on behalf of the poor. There will be expected tensions in advocating for the poor in the public square, including opposition from within and from outside the church community. The political process is rarely comfortable for those with deep, conservative biblical convictions and is often beset with estranged alliances and awkward compromises. Additionally, the very poor we seek to serve will not always appreciate or rise up to the advocacy afforded to them. Nonetheless, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer said, we need to “smudge” ourselves with “the hard complexities of the world” [Elshtain’s “Afterward” in Evangelicals in the Public Square by Budziszewski, 197]. *Adapted from chapter 1 of Wasted Evangelism, "Widows in Our Courts."  In light of Mark’s association of the kingdom with the gospel (1:14–15) and the gospel’s programmatic association with the Exodus land-laws [in particular see the connection in the opening (Mark 1:1-3) references to Exod 23:20 and Mal 3:1-5 and the texts surrounding context], I propose that biblical social action is a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor. Stephen Mott, former Professor of Christian Social Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, points out that the Bible speaks of what is called “social action” in terms of carrying out justice and caring for the needs of the weak. In her book, Social Justice Handbook, Mae Cannon affirms a similar understanding of the biblical concept of social justice: The resources that God provides were made available to his people from the very beginning. Justice is expressed when God’s resources are made available to all humans, which is what God intended. Biblical justice is the scriptural mandate to manifest the kingdom of God on earth by making God’s blessings available to all (Mae Elise Cannon, Social Justice Handbook, 22). *Adapted from the introduction ("Evangelism and Social Action: An Exegetical Argument") and the 2nd chapter of Wasted Evangelism, "Wasted Evangelism (Mark 4): Social Action Outcomes and the Church’s Task of Evangelism."

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed