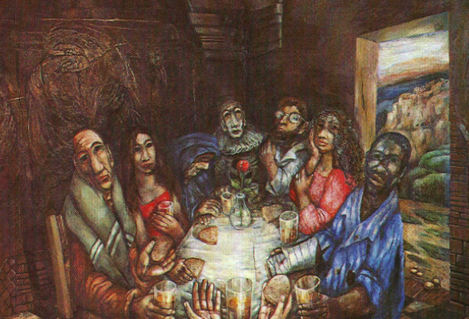

If you caught this yesterday, my sermon text for Sunday is Galatians 4:8-20. A text that reveals Paul’s heart for the Galatian house churches and his perplexity (v. 20) over why the Gentile Galatians would even consider adopting—even more so, getting circumcised and identifying with--the Law and, thus, old age, living in exile, under the covenant curse Israel current position before God? Breaks his heart (as this text reveals). In this section, Paul also tells the Galatian house churches what his goal is. This is found in verse: “my little children, for whom I am again in the anguish of childbirth until Christ is formed in you!” (V. 19). Most English readers take the “you” as “you individuality,” assuming Paul means “I desire to see each Christian looking like, acting like Jesus.” While this is a good thing of course—and would be if that’s what Paul meant here. But it begs the question: What does looking like and acting like Jesus look like? And, is Paul referring to the individual Christian? Here in this text, not only is the “you” plural, it is a part of a prepositional phrase: ἐν ὑμῖν (“among you,” i.e., among you, the house churches in Galatia). So, Paul is saying, “My little children [those whom I led to Christian among the house churches in Galatia], for whom I am again in the anguish of childbirth until Messiah is formed among you.” It is so much more preferable to take the “in” (of most English translations] as “among,” a perfectly reasonable rendering of what Paul wrote. Now we should ask what does Paul mean by formed “among” the house churches in Galatia? The apostle has already told us in chapter 3. “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (vv. 27-28). Since the Law has fulfilled its purpose (which is why it was temporary and why it is so perplexing you--Galatian, Gentile Christians--would even consider circumcising yourselves to this Law), additionally, you all have been baptized into Christ, listen, and now there is neither Jew nor Gentile; there is neither slave nor free; there is neither male nor female—you all are in Christ and you all are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise [given to Abraham].” This is what is means to have Christ formed among them, namely churches that present “neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female” (3:28); house churches where “you are all one in Christ Jesus” (v. 28d). This observation makes me think that when our churches are majority peer-like congregations, I wonder if we are then returning to the elementary principles that govern the world—or, as Paul says in our text, we have returned to idol-worship.

0 Comments

Some sermon prep thoughts . . . the fuller text is Galatians 3:23-4:7 . . . and yes, this is a Christmas Season Sermon text . . . See Galatians 4:4. The part I am reflecting on is the well known Galatians 3:27-39: “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ's, then you are Abraham's offspring, heirs according to promise” (Galatians 3:27-29). I am not sure that we fathom how radically deconstructing these words would have been for the Greek, Roman, and Jewish man, especially male head of households, who were also masters of household slaves . . . nor can we (but we should) grasp the radical reconstruction and liberation these same exact words would have been to the Greek, Roman, and Jewish women and slaves and free (emancipated) slaves, who had no home or legal status whatsoever . . . interestingly we forget that Paul just mentioned sonship (“you are all sons of God, through faith,” v. 26) and will soon talk again about sonship and heirs (Gal 4:1-7), that is, being sons of God. I know we like to be modern and relevant and say “sons and daughters of God,” attempting to get past the so-called ancient gender-bias; but this is both unwarranted and does injustice to the text in its culture—depriving the Christian, especially the female Christian, of its impact. “Sons” were everything in the Greek, Roman, and Jewish world. They got everything. They had far more respect. They got citizenship. And if you were the first born male, an heir to family wealth, possessions, land, and legacy. The goal of marriage to the Greek and Roman was to produce a legitimate male heir citizen for the Empire. So, to deprive the female Christian direct title “son” with all of its rights and privileges (as it would have meant to the ancient world reader) would simply be not right, unfair, unjust, unbiblical . . . it would not be Christian. The impact of such sonship on the Jew, the Greek, slave or emancipated slave is left with no contemporary translative spin—as it should be. Yet, our cultural sensitivity (although sincere and well-meaning at times) toward the gender-bias we have robed the sister in Christ of the applicable impact on her status as a “son of God.” And, for sure, this simple slight of hand turning “sons” into “sons and daughters” makes us (you know I mean, us brothers) feel as if we’ve (they’ve) solved all the gender-bias (male-dominating, male-centrism) within Christianity and its religious systems, habits, and attitudes with one easy “translation” fix. In some since, this translative adaption helps to lessen the power of this text to deconstruct our male-centeredness and robs the church from allowing the place of the female to be reconstructed into the place of a “son of God.” It is no wonder the early church grew as it did . . . and it is no wonder why women were especially attracted to the fulness of time when God sent his son, “born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Gal 4:4).

“And on that day a great persecution began against the church in Jerusalem, and they were all scattered throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria, except the apostles” (Acts 8:1b, NASB). “Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To those who reside as aliens, scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, who are chosen according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, by the sanctifying work of the Spirit, to obey Jesus Christ and be sprinkled with His blood: May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure” (1 Peter 1:1-2, NASB). ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ Imagine. If you can. You are a small gathering of Christians in the first century. The new born church that we meet in Acts, now scattered throughout the Gentile world. A very minority church in the Roman Empire up to about 150 C.E. By now, most of Christian fellowship, instruction, and worship was done in homes, catacombs (underground cemeteries), workshops (that were also apartments) or hidden away, or above the streets, in tenement-styled, stacked row building apartments. Imagine. The “gathering together,” what we could have called “a church,” is still illegal, at least not recognized as religio licita, a permitted cult or religion in the Empire. Imagine. That fourth and final cup after the meal was over (Luke 22:20; 1 Corinthians 11:25), still treasonous, lifted, now not to Caesar, but to honor Jesus, risen and Lord. Gathering together was still very dangerous. A non-domestic building, set aside for Christians to gather for worship, was still many decades off, probably 200+ years in the future. The earliest separate building devoted to Christian use was in eastern Roman Syria at Dura Europos on the Euphrates River. Originally a house that had come into a Christian's possession and was remodeled for church gatherings in the 240s CE. But still, it wasn’t like church buildings were popping up all over the place after Dura Europos. It would still be another century before non-domestic buildings would more readily (and permitted to) be built or designated specifically for gatherings of believers to function as a “church building.” And, still, even around 350 CE, there won’t be a boom of church buildings going up everywhere.

We, too often, work backward from our building-experienced-church to the New Testament, imagining the church we read of in Acts (and Romans, 1 Corinthians, Philippians, et al.) or read of the first century church as being all made up of these small groups of somewhat organized believers that gather (albeit) in homes as if they are free to do so often, let alone, weekly. Yes, of course this happened. Just not as neatly as we imagine. The church of Acts and the early (first century) church is far more scattered, less free to meet, than we imagine. A clandestine church is more likely a better way of thinking “church” for the first 150 years or so. We simply do not have an imagination of the church as revealed in the New Testament. Why is this important? First, it, that is, the house-church, is how God choose to reveal what He meant by church, a gathered-church. Yes, the difference between “form” and “element” is important; but form develops habits that sneak in to determine element. The form of the New Testament house-church developed habits that taught something about the nature of church as do separated buildings teaches something about church. And, secondly—and to the point in this piece—churches in the New Testament and in the early church didn’t have the privilege of a legal means of or a culturally acceptable means to gather once a week on a day that is (like our Sunday) a “day off” in what would be, more than a millennia off—something come to be called a “weekend.” Today, with this COVID-19 crisis, what we have is a very non-ordinary time. For us, here in America, at least. For quite some time, we have been pretty much guaranteed the freedom to gather together as churches. And boy do we. All types of church. Big. Medium. Small. In all types of buildings. While there are some home-church movements, most church congregations meet in separately addressed, non-domestic buildings of some kind. Yet, still, even now, there are many churches throughout the world that do not have the freedom to gather together—some because they are oppressed; some because they must hide; some because there is no such thing as a weekend; and, some are simply too poor and exist in under-developed or third world nations (or, even, neighborhoods).[§] These churches are much closer to the young church than we can imagine. But, we are beginning to imagine. Still, it is hard to imagine a church as a “scattered church.” However, I believe we need to have this imagination now.

We also need to understand that these “scattered” would not have had “churches” to move into, or established fellowships to embrace, and no places into which they’d be welcomed as “churches.” They were indeed “scattered” without (at least immediate) access to the Apostles (who stayed in Jerusalem, Acts 8:1)—which would have meant no communion (as we know it), no qualified preaching or instruction from the Word and/or Words of Jesus, et al. Indeed, they were scattered. In the 1 Peter passage, we have a church that is described as geographically “scattered” throughout Asia Minor. And, of course, this “scattered” are small household-churches, gathered together, but still, we need to embrace the term “scattered.” This text, also, tells us that nothing is lacking in this “scattered” church. Though “scattered,” these household-churches were chosen (aka, the elect); all are completely caught up in the sanctifying work of the Spirit; all are charged to obey Messiah Jesus; all fully sprinkled by His blood (i.e., made pure). This spiritual equity is also pointed to in the blessing that Peter immediately brings in his address: “May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure” (1:2d). The whole of Peter’s first letter describes a church in crisis, amidst culturally formed suffering: “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you” (4:12). This affirms that a “scattered” church is a church responding to crisis, under some form of suffering, threat, and/or pressure beyond its control that disrupts everything for them. Of course the word “scattered” is a pun on the Jewish Diaspora (i.e., the scattered ten tribes of Israel). Yet, this pun works because the young church (or better, young churches, plural) existed in a hostile environment, one of (at least local) persecutions, where their neighbors, families, and whom they commerced with, all hold to a polytheistic worldview, and in a surrounding culture that is all about legality (i.e., being considered a legal citizen with standing before the law), blood legitimacy, and social standing (i.e., honor). What is interesting, this pun, being called “scattered” is indeed like the Jewish Diaspora, which had no temple and living as aliens in strange lands (i.e., the idea behind “resident aliens” of 1 Peter 1:1b). This is “scattered” church. This last description is important, for scattered Israel in and throughout the Greek-Roman world had to learn to be God’s people in a time and in a land not formed by their religious values and habits. In a foreign, strange, alien world. In a land where they had little to no control or power over their religious habits. Prayer and the Word became very central to scattered Israel. Even non-Diaspora Jews (what we mostly meet in the Gospels) were, as well, not in control of their religious habits. Sure, they had the temple, but it was tolerated and governed and watched over by pagans (aka, outsiders, polytheists, Caesars, haters), who only tolerated the people of Israel (not who accepted them as equals).

I don’t think we could have imaged, even three months ago—or even for that matter, ever—that we’d be “ordered” (or pressured) to not gather as churches. To be cut off from our buildings that offer take-for-granted habits we interpret as biblical and essential to understanding “church.” To be separated from other members of our own congregations that plays tricks on our assumed biblical concept of “church.” This is a time for our imagination of church to include being “scattered.” This imagination will prepare us for the (real) trials to come. And you need to understand, this is not the trial, but only a preview of what is to come. Someday. Three months ago, we would not have thought it possible to be at this place, being his “scattered” people, a church not in control, regulated by outside pressures and forces, unable to freely meet together. It is of note, especially with regard to the “scattered” nature of the church in 1 Peter, that, as a “scattered” church, the test or trial is not solely one of individualized faith. As a “scattered” church, what is being tested at this time is loyalty (the actual meaning of the word “faith,” πίστις, pistis). Are we loyal to Jesus and are we loyal to his body? And, by “his body” (aka “the body of Christ”), I do not, as I believe the New Testament writers do not, mean some notion of a universal, invisible church, but loyal to a local body of Christ, consisting of actually flesh and blood fellow believers. An imagination of “scattered church” will help us to learn new habits that build the body, that strengthen our fellowship of believers, and, very importantly, habits that proclaim in Word and deed that we are followers of Jesus, so that, publicly, others will know that we are Jesus’ disciples (John 13:35). We are, local and in all locales, a church in crisis. Right now. And, this makes us “scattered” churches. We endure, although scattered, yet together in Christ, so that perhaps, through our suffering, God’s elect [wherever our “scattered church” exists--for us, the Hill] may obtain the salvation that is in Messiah Jesus (2 Timothy 2:10). Let us remember, as “scattered church,” we are no less church. We are the full-body of Christ, though scattered. We do not lack anything from God as a scattered church. Even now as scattered church, the blessings of Peter is completely ours in Christ: “May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure.” [§] A Third World country is a developing nation characterized by poverty and a low standard of living for much of its population.

We will take a look at the “Triumphal Entry” story in Matthew 21 on Sunday morning. The population of Jerusalem, normally, was about 30,000, yet with the passover and all its events and activities, the city's population had grown far beyond its capacity to about 180,000. Inns were full. Family homes packed to overflowing with relatives. Camps of make-shift tents filled almost every space around the city and its outer hills and valleys. And, then, Jesus arrives. The crowd cheering him on as he rode that colt of a donkey was not (necessarily) only visiting guests and residents of Jerusalem that day, but the throngs, that is, the crowds that had been following him from Galilee--many were Galileans for sure (very much outsiders), but certainly many of those whom Matthew has already described to us elsewhere:

We know this crowd was following him down to Jerusalem: “And as they went out of Jericho, a great crowd followed him” (19:29). The sheep-without-a-shepherd crowd that Jesus had compassion for (cf. Matthew 9:36), these had followed him to the city and are, most likely included in those cheering the arrival of Messiah, of the King, who had come to save them all. In fact, we know this by Matthew's own accounting, for after the table-turning event that cleared the temple court of illegal and irreverent merchandizers preying off the weary travelers coming to Jerusalem for the Passover, he writes: This happened in the cleared court of the temple. Matthew tells us, as the events that day in the temple unfolded, that the Jerusalem crowd had asked "Who is this?" for the "whole city was stirred up” (v. 10). Of course it was, this Preacher from Galilee had arrived, acting all king-like on that colt of a donkey, and the throngs of outsiders, many considered unclean, that had been following him were now occupying the temple courts and disturbing the social and religious festivities. The unclean (blind and lame) and those outsiders in the temple! Outsiders. Lame. Disabled. Demon-posessed (many whom Matthew's story thus far has told us were freed). The sick. Infirmmed. Those with seizures. And, their families. Did I mention outsiders? Galileans. And, even those perhaps from as far as Syria (Matthew 4:24). Throwing down palm branches. Shouting, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!” (21:9b). All proclaiming Jesus as king of Israel. And, then, Jesus makes space in the temple for them. All this was not received well by Jerusalemites (i.e., the probably crowd shouting condemnation before Herod later in the story) nor, especially, the temple-leadership (v. 15). When Jesus tells the two parables of the one son who rejected the Father's work and how the first disrespectful son repents and does the will of the Father, and the fake, greedy servants killed the Father's son . . . it is no wonder the temple-leadership felt this all was about them. Now, to do away with this king, this messiah . . . How can we, today, as church, run away from the inspired narrative that clearly shows that Jesus accepted the blind and the lame (surely a summary of all those sick, oppressed, and poor) into the temple, upsetting the status quo, deconstructing the religious institutional bias toward the powers and powerful, the wealthy and affluent? What do we make of this? Church, we need to do better. O, Christian, we need to rethink church.

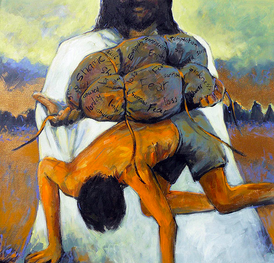

One of my heroes of the faith is A.B. Simpson, founder of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (1843-1919). Called to a rather prestigious NYCity church (a Presbyterian church!), he began to have a burden for ministry among the poor and street people. He'd preach on the street; street people converted; and, he brought them to church . . . was summarily disciplined and removed from the pulpit (on record, it was over his changed position regarding baptism, but there is no doubt as to the real reason was bringing those people into the paid-pews of our church). Having those street people (i.e., the bottom demographics of NYCity) enter Simpson's church was like the time Jesus took to turning-tables and whipping merchants who filled the temple court (probably Court of the Gentiles) and, then, the crowds of the poor, marginalized, sick, disabled came into the temple (assuming there was a place for them now that the merchants were chased out) . . . Jesus overturned the status quo and mis-use of the temple sacred space and the very crowd that was disallowed, then, came in . . . We often read past quick verses that give some context to the narrative. Matthew's account tells us immediately what happened after the table-turning: “And the blind and the lame came to him in the temple, and he healed them” (21:14). Matthew then tells us the temple leaders “were indignant” (v. 15). The Matthew 21 OT quote used to prophetically justify Jesus’ table-turning action was to remind Israel’s temple-leadership that God's temple was to be a house for ALL people (Matthew 21:13; cf. Isaiah 56:7). When we turn to that Isaiah 56 quote, we read in the very next verse: “The Lord God, who gathers the outcasts of Israel, declares, ‘I will gather yet others to him besides those already gathered’” (v. 8). And, this is exactly what happened in the over-turning-tables story in Matthew–in the very next verse: “And the blind and the lame came to him in the temple, and he healed them” (Matthew 21:14). If one pulls out the other likely OT reference to a “house of prayer for all people,” namely Jeremiah 7:11, there, too, we find in the context the marginal and bottom-demographics that have been left out, for we read in Jeremiah 7:5: “For if you truly amend your ways and your deeds, if you truly execute justice one with another, if you do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow . . .” (v. 5). Let's get this right: the over-turning-tables scene is about God’s people (more so, the visible ones that makes up both the truly elected and those who claim Christ but are not necessarily truly God’s people), the very temple (i.e., the place of God's dwelling and manifest presence--which was the temple in the OT and now the visible church, i.e., churches scattered throughout the earth) has barred the marginalized and placed barriers to the bottom-demographics from the temple/church sacred space. Like Jesus as he makes room for them in the temple, the significance of this Matthew 21 text is to apply to church (not in a general, universal church way--whatever that is--but, to the local church, my church, your church) by the intentional creating of room, restoring sacred space (i.e., literally NT table fellowship, however it looks today) for the bottom-demographics to be among us (or us among them, better, still). Or, we, too, may face Jesus’ over-turning-tables judgment.

patterns of church) and execute justice one with another (i.e., our neighbors) and not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow . . . among church. This is not a State funded plan or program. This does not need to come from the Supreme Court or any federal law. This is church. Is it no wonder we hear a few lines later, in Matthew 21, Jesus would tell the temple-leadership who had a problem with the incoming bottom-demographics: “Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and the prostitutes go into the kingdom of God before you.” This is an ecclesiological (aka a church) issue, the neglect of our poor and marginalized neighbors, and the giving of access to our fellowship so that they may have full access to the Father. We need to rethink church.

Many Christian advocates for social justice cry out for deconstructing privilege and the privileged from a platform of privilege themselves, a place of power, celebrity, notoriety, and/or money (not to exclude address, i.e., where they live and the resources at their disposal). Over and over, their advocacy seems to contradict their status and lifestyle. These same advocates for social justice use the Bible (and for the most part I align and, even, agree with much of their message; not so much their means, which are, for the most part, not biblical, but mostly cultural, political, and status resourced). Here’s what strikes me: The original advocacy (i.e., the gospel of Jesus, the Messiah) and how it changed things, how it deconstructed, and, then, reconstructed habits and lives and attitudes did not occur from the place of power, but from the place of powerlessness. We learn this, first, from the humanizing (i.e., incarnation) of the One who was in the form of God from all eternity taking on the form of a slave (Phil 2); and, second, from the small gatherings of believers in homes (living rooms), we now call churches, made up mostly of the poor and powerless in the early decades of the church. Of course, there were some wealthy among them and some who provided homes for churches to gather; yet, here, too, as Christians and people that used their homes for believers to gather would have lost their status and social standing (at least in part), leaving them to be classed among the powerless and the bottom-demographics of the Roman Empire and Greek world. It would be nearly three centuries before the wealthy, educated, and powerful had control over the affairs of the church. No longer in homes. State (i.e., Empire) sanctioned and often constructed buildings became the addressed-venues of churches. Highly trained and Empire sanctioned clergy had authority over the church. No longer food for a supper, but tokens of bread and wine were used and guarded and distributed by this now elite, often cosmopolitan, clergy. Now, the State (or Empire) controlled the advocacy, that is the results of the gospel. The poor and the powerless among the Christians were separated from their more wealthy, educated, and affluent Christian brothers and sisters, by design and by default. Yet, it was not so in the beginning and for about 300 years of church history. Obviously the shift crept in, but was not fully established until the Emperor “converted” (but was not baptized) and the Empire started creating a space of power for the leaders of the church. My concern here is not to dwell on how the church came to know power and has been able to produce power and the powerful, but to highlight that our present social justice advocates do so from a platform of power that the very gods of empire (call it as you will, colonialism, Christendom, American upward mobility—no matter, it is the powers that) has given (such power) to them. Few seem to divest themselves of power and privilege (as did Jesus, whom they say they follow) and take on the form of a slave and being obedient to the point of death, even death (i.e., dying to self) on a cross (again, cf. Phil 2) on which they are called to carry; but, yet, offer, still, their justice rhetoric and (really what is often simply) political vision from a place of culturally designed privilege and power. Until this is recognized (and deconstructed I might add), such advocacy will rely on the power of the State to enforce their vision (no matter how clothed in biblical language it might be). It is my humble opinion that we need to rethink church, especially as the place where systemic change happens, even though it is a place (and the space) of the poor and powerless. (Well, it should be.) Of course, plenty of “churches” need repentance, an attitude of lament, and a call back to the gospel (liberal, progressive, and conservative churches), but, nonetheless, it is, still, the church (local churches) where the alternative of God’s kingdom is to be lived (by believers) and observed (by outsiders). (Not “look how we vote” or “look how we protest”; but “look how we live and fellowship as strangers and unequals, as brothers and sisters in Christ, a wholly new family in Christ.”) The church, a church, local churches scatter from street to street, neighborhood to neighborhood, places where strangers and unequals meet over a meal (break bread) and celebrate (raise a cup) that they have no other Lord than the risen Messiah, who sits at the Father’s right hand (their only source of power, which is lived by denying themselves and taking up a cross). Such advocacy should not rest in individuals who have forms of cultural power at their disposal, but an advocacy that stems from a gathered-household of faith. Social justice advocacy should be a lived-church thing (and for that matter, the place of no power, no culturally derived and given power). Social justice is a lived-church advocacy. Our advocacy for social justice, like any of our boasting (our culturally, socially, and economically derived desires, vision, or means of power), needs solely to be first and foremost “in the Lord” and made from a willing place of foolishness. Our social justice advocacy platform, the place where we are “like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things,” this is the place, Jesus’ church, local churches, find themselves and where authentic social justice advocacy has its gospel platform.

Some preparation for this coming Sunday’s teaching/sermon and some exegetical fun with Ephesians 4:11 (for those that like this sort of thing)

Elsewhere in the New Testament (and in Greek literature in general), when a writer strings words together, that is creates a run-on list of related words (cf. Ro 12:2; Phil 4:6), the sense is to describe the same thing, that is one thing. So what we have, here with Paul in Eph 4:11, probably should be taken in the manner of other similar Greek stringing to emphasize “teachers” of the church—“the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds” (noting and leaving in the repeated use of the definite article, “the” (τοὺς) that is left out of many English translations). The καὶ (and) that precedes the word διδασκάλους (teachers) should, most likely, be read epexegetically, that is with the meaning “namely” or “that is” (in this case because of the string of words, “namely that are”). The “teachers,” then, explain the nature and give summary (the point) of the previous string of words, “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds.” Most older English translations mask the obvious string by inserting the word “some” before each office. The NIV and ESV give the sense of the original (Greek) by showing the definite article that is used (τοὺς, the) before each in the string. The exception is with διδασκάλους (teachers); there is no preceding definite article. Some (I used to) just take the lack of an article to be linked solely to “the shepherds” (τοὺς δὲ ποιμένας καὶ διδασκάλους)–i.e., shepherds that teach; yet there is good sense to see the whole string (which is very reasonable and most likely) to be in the frame of the epexegetical phrase καὶ διδασκάλους (namely, that are teachers). Thus, my reading: “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds, namely [καὶ], that are teachers.” This makes grammatical and syntactical sense of the string and the repeated definite articles, and the lack of article with “teachers.” (See below* regarding my comment on the μὲν . . . δὲ construction, on the one hand . . . and on the other). We should read Ephesians 4:11: “God gave, on the one hand (μὲν)* apostles [who set the foundation of apostolic teaching and traditions (cf. Acts 2:42)], yet (δὲ) on the other hand, [He gave] teachers that speak-forth the Word (i.e., prophets), that proclaim and spread the good news (i.e., evangelists), and that guard, protect, feed (instruct/disciple), and care for the flock (i.e., shepherds).” I believe, given the wording and syntax of this verse, what I propose here is a fair and faithful reading of Paul’s intention for writing this to the church in Ephesus. The “apostles” are foundational in that they, historically, passed on (i.e., Peter, John, James, et al.) or delivered (e.g., Paul, Barnabas, et al.) the apostolic traditions (i.e., the teachings of Jesus and their intentions) at the first as churches where planted and spread throughout the known world. On the other hand, “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds” are the “teachers” that continue to pass-on apostolic tradition/teaching to the gathered-believers (or local churches) as the word spread and took root geo-demographically. I take the first office (“apostles”) as temporary once for all time and the second set of offices (and if you don't like the word office, “roles,” then, works just fine) as teachers for the gathered-churches to cause unity, maturity, and growth throughout time until . . . the word Paul uses (4:13) . . . until the fulness of Christ is accomplished in time and space on planet earth (cf. 1:10; 22-23; 3:19; 4:13c). In the rest of the paragraph (Ephesians 4:12-16), we will learn that these people—note: I take these more so as offices (or, again if you prefer, roles) filled by people (who are able and/or appointed to pass on apostolic teaching) because, rather than using a relative pronoun, i.e., those who prophecy/forth-tell, who evangelize, and who shepherd, Paul is intentional in using the definite article (τοὺς, the) before each word—they are given (i.e., gifts) to God’s people to move them toward the unity of the faith and the knowledge of God’s Son, toward perfection (i.e., maturity), and toward the fulness of Christ (that is being church, which is His body in locales, scattered throughout the earth, i.e., churches). At CPC in The Hill, we have, for a number of weeks, heard in the Gospel of Matthew about Shepherds and God expecting that teachers were to carry on the work of the ministry in the church. We noted that sheep die without shepherds (cf. Matt 9:35-38). We have heard about bad/poor/false leaven (i.e., teaching) and that we must take serious the instruction of a cross-centered teaching (Matthew 16 for example). So, our little detour in Ephesians this coming Sunday isn’t all that much a detour. Note Paul's link to shepherds in Ephesians 4:11.We will be discussing the need, significance and importance of developing teachers at CPC in The Hill. *μὲν is usually not translated, however, the μὲν . . . δὲ construction should be understood as “on the one hand . . . and on the other,” thus my translation. Furthermore, each δὲ in the string strengthens the reading that each office/role is included with the epexegetical καὶ (namely, that are).

The systems (by design, default, and/or from unintended consequences) that are in place that create and sustain the conditions of poverty and our current social structures are near impossible to change. All the political and progressive rhetoric is ill-equipped to actually offer alternatives to the current conditions of poverty. Social boundaries, the ability for mobility (cultural, social, educational, economic, et al.) are mostly set in concrete, near unchangeable. Furthermore, those who have a vested interest in their own place and status (wealth, social, location, power) have no, sincere, vested interest (beyond appearance, mere rhetoric, or progressive voting) in changing the systems now in place. On the other hand, those in the bottom demographics do not have the power, do not live in geographic spaces, nor have the educational skills to make any significant change to the very complex, hierarchical-engendering, boundary rich, mobility disabling systems in place that keep most everybody in their social, economic, and cultural corners (socially, geographically, demographically, educationally, et al.) The spheres of government and of social-service (private and public) do not have the truly vested, self-less interests in making change. The appearance of change, perhaps. The rhetoric of change, perhaps. The political allegiance, perhaps. But not real, systemic changes that would actually release mobility beyond the current “corners.” When will we learn this, O Christian? Yet, as strange, foreign, and impossibly crazy as this sounds, the only space where the good life, flourishing, and even systemic social and cultural change to offer real mobility beyond our current “corners” or even truly be imagined is the gospel-rich church–literally amid local churches scattered throughout communities. Amid local churches where there is no earthly power being sought (even by its leadership), but the love of neighbor (and neighborhoods). Amid local churches where an individual’s humanity is honored, prized, and even died for is a result of believing in the gospel of Jesus Christ. This is the space, amid the early church, in which such change was nurtured and, albeit slowly, happened at the heights of the Roman empire. Where it actually outlived an empire. This is the space in which such changes have happened on small and large scales ever since. Where all lives literally matter; and, when there are lives deemed lesser, treated lesser, those lives matter more, intentionally more. The space where the hierarchies of tiered humanity are deconstructed and the alternative is constructed–that alternative is the kingdom of God, realized in Christ Jesus, and revealed through the church (literally through churches scattered in countless neighborhoods and communities). In the social and governing spheres where it takes power to make systemic changes, it will also take power to maintain such changes. And, this maintaining power is always violent. Furthermore, human nature (in the church we call it our sinful nature) will not, however, relinquish its desire for maintaining one’s advantage over others and freely disinvest its self-interests on behalf of others. So once systemic changes are make (where there is power to make such change), there will always be the powerful and powers that will seek to mark their place and status (i.e., those who make the laws have the power to enforce, by means of violence, their laws); also, there will always be those who obtained newly created social elite status, those who become affluent because of the changes and, then, will seek systems to exercise power (political and social) to maintain the new status quo (their new power). Thus, the boundaries remain and the violence to maintain them continue. This is not the way of the gospel; and, thus, not the nature of the church (read local churches scattered among communities, neighborhoods, regions). This is why the local, gospel-centered, gospel-rich, gospel-dependent, gospel-lived church is the only real space where such social change can truly be experienced. Church matters (#churchmatters). #churchmatters: Gathered believers are sacred space (not the room or building they meet in)5/27/2019  “The church (read a gathered-church) does not need a ‘sacred place’ to worship, have fellowship, and to offer (apostolic) instruction–three things the apostolic and early church would not have separated–for those gathered are the sacred space. In fact, the local gathered-church is the liminal space between the heavenly places and earth; the human beings, who have gathered together, are the most sacred space, the holy of holies as it were (literally), in all of creation at that moment; they are, not the space or place, the address, they occupy, the temple of the Most High, the Creator God of all creation; they are the mystical, yet visible body of Christ, that is, the presence of God in Christ on earth, right there, because their ascended Head, Messiah Jesus, is now seated at the right hand of God in the heavenly places and they, these gathered believers are His body” (CMA). Church matters (#churchmatters)

IV. Our Church Life should be an Invitation to Come to Jesus, take His Yoke, and You will Find Rest: We are to embody the invitation to Come Our little Hill church puts itself into the heart of the community: at the Hill North Community Management Team, the Free Sidewalk Breakfast each Saturday, our Summer Park BBQ ministry; showing up to almost every community event, and my pastoral street counseling right out my front door. When John the Baptist was facing the end of his ministry (in Matthew 11), he told his own disciples to go ask Jesus if he was the One or should they look for another (was this for John or his disciples, I have my opinion on that, but it is surely for the church). How do they know Jesus is the One and there is none other to look for? Jesus asks them what they see (which implies action, demonstration, something happening): How do they know? ➥ the blind receive sight ➥ the lame walk ➥ lepers are cleansed ➥ the deaf hear ➥ the dead are raised up ➥ the poor have the gospel preached to them (Matthew 11:4-6) This is exactly what Jesus has been doing as his disciples followed him around. No doubt this is Matthew’s version of Luke’s draw on Isaiah 61, which promises that God’s Spirit would be on the Messiah to preach the gospel to the poor, to heal, to free and bring justice (Isaiah 61:1). This is the context in Matthew. This is exactly what Jesus is doing. This is what the temple and synagogue leadership miss, ignore, or are fighting against.They are still bothered for in Matthew 11:19 there is more accusation: . . . they say, ‘Look at him! A glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners!’ We end our thread in Matthew 11 where Jesus invites all who labor and are heavy laden to come. First, Jesus praises the Father that “all things have been handed over” to Him “and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.” As Presbyterians, we identify with this divine election. Yet we forget that the means of grace to call the elect is given at the same time: 28Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. 29Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. 30 For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” Recently during a Hill Sunday sermon on Matthew 11, I asked my own congregation: “How do you think the young church, with nothing much to offer, no social or political power, possessing little resources—and life didn’t really get easier and better for early believers. They risked everything, and for most, life got harder. In the first 150 years after Pentecost, how did Christianity became the largest religious sect in and around the Roman Empire? How? They accepted all into their fellowship, this changed their households . . . street by street, village by village, table by table. It all changed where gathered-churches lived out “Come all who labor and are heavy laden.” The body of Christ, the local church, with Jesus our Head, ruling and reigning at the Father’s right hand, is His presence in the community, in the Hill community, in your community right here in Concord. We show them Jesus by who we are and what we do so that all who struggle and toil and are carrying burdens no one should carry alone (because they see) hear the invitation to Come to Jesus and take on His yoke and find rest. We are to embody the invitation to Come. We need to be refreshed in the gospel every time we gather because we need the power of the gospel in order to be the gospel in action. I might get everything else wrong about church planting . . . I might not even be very good at it, at least not good at what is expected . . . but one thing I will get right, by God’s grace, to help the CPC in The Hill flock understand and know what it means to follow Jesus around . . . Our church does this . . . even though we are a church in an under-resourced community, we spend ourselves on our community, attempting to associate with the lowly, the hurt, those who's lives are messing, unclean, spoiled, and forgotten. A church needs to be where crowds are (out in the ebb and flow of community life): this is why our small under-resourced church spends its time in the community, places where crowds show up. This is what it means to follow Jesus around and it is how others know that the kingdom of heaven has appeared. *This sermon was preached at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Concord, MA on Sunday, May 19, 2019. The full sermon maybe downloaded as a PDF (here). An audio version is also be available >> Audio version Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed