IV. Our Church Life should be an Invitation to Come to Jesus, take His Yoke, and You will Find Rest: We are to embody the invitation to Come Our little Hill church puts itself into the heart of the community: at the Hill North Community Management Team, the Free Sidewalk Breakfast each Saturday, our Summer Park BBQ ministry; showing up to almost every community event, and my pastoral street counseling right out my front door. When John the Baptist was facing the end of his ministry (in Matthew 11), he told his own disciples to go ask Jesus if he was the One or should they look for another (was this for John or his disciples, I have my opinion on that, but it is surely for the church). How do they know Jesus is the One and there is none other to look for? Jesus asks them what they see (which implies action, demonstration, something happening): How do they know? ➥ the blind receive sight ➥ the lame walk ➥ lepers are cleansed ➥ the deaf hear ➥ the dead are raised up ➥ the poor have the gospel preached to them (Matthew 11:4-6) This is exactly what Jesus has been doing as his disciples followed him around. No doubt this is Matthew’s version of Luke’s draw on Isaiah 61, which promises that God’s Spirit would be on the Messiah to preach the gospel to the poor, to heal, to free and bring justice (Isaiah 61:1). This is the context in Matthew. This is exactly what Jesus is doing. This is what the temple and synagogue leadership miss, ignore, or are fighting against.They are still bothered for in Matthew 11:19 there is more accusation: . . . they say, ‘Look at him! A glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners!’ We end our thread in Matthew 11 where Jesus invites all who labor and are heavy laden to come. First, Jesus praises the Father that “all things have been handed over” to Him “and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.” As Presbyterians, we identify with this divine election. Yet we forget that the means of grace to call the elect is given at the same time: 28Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. 29Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. 30 For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” Recently during a Hill Sunday sermon on Matthew 11, I asked my own congregation: “How do you think the young church, with nothing much to offer, no social or political power, possessing little resources—and life didn’t really get easier and better for early believers. They risked everything, and for most, life got harder. In the first 150 years after Pentecost, how did Christianity became the largest religious sect in and around the Roman Empire? How? They accepted all into their fellowship, this changed their households . . . street by street, village by village, table by table. It all changed where gathered-churches lived out “Come all who labor and are heavy laden.” The body of Christ, the local church, with Jesus our Head, ruling and reigning at the Father’s right hand, is His presence in the community, in the Hill community, in your community right here in Concord. We show them Jesus by who we are and what we do so that all who struggle and toil and are carrying burdens no one should carry alone (because they see) hear the invitation to Come to Jesus and take on His yoke and find rest. We are to embody the invitation to Come. We need to be refreshed in the gospel every time we gather because we need the power of the gospel in order to be the gospel in action. I might get everything else wrong about church planting . . . I might not even be very good at it, at least not good at what is expected . . . but one thing I will get right, by God’s grace, to help the CPC in The Hill flock understand and know what it means to follow Jesus around . . . Our church does this . . . even though we are a church in an under-resourced community, we spend ourselves on our community, attempting to associate with the lowly, the hurt, those who's lives are messing, unclean, spoiled, and forgotten. A church needs to be where crowds are (out in the ebb and flow of community life): this is why our small under-resourced church spends its time in the community, places where crowds show up. This is what it means to follow Jesus around and it is how others know that the kingdom of heaven has appeared. *This sermon was preached at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Concord, MA on Sunday, May 19, 2019. The full sermon maybe downloaded as a PDF (here). An audio version is also be available >> Audio version Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

0 Comments

III. We demonstrate the presence of the Kingdom by sending Laborers into God’s Field to do what Jesus did We have moved into the Hill. We relocated. (You all made this possible—thank you.) This is important: most pastors of churches in places like the Hill don’t live in the church’s neighborhood. Our moving into the Hill is a big deal—that’s what our neighbors tell, too. This is huge because there is a connection between the gospel and the community . . . between Shepherds and the community . . . between churches and the community. No wonder Jesus calls for laborers for the harvest. Another summary at the end of Matthew 9.

The reason for Jesus’ compassion is that they were sheep without a shepherd, harassed and dispirited. Jesus mixes his metaphors and says that there is a need for Shepherds for the Harvest is rip. “Harvest” is a great eschatological, end time word used throughout the Old Testament. “Harvest” means we are in the age of the appearance of the Kingdom of Heaven, but it also suggests that the end is near (of course eschatologically near, but also timely, the time to harvest is now; this gives us an urgent frame for the task). We should not be surprised that there is a relationship between this crowd of outsiders, unclean, lame, diseased, their condition (harassed and dispirited), and the absence of a Shepherd. People die without a shepherd. This is why we pray to the Lord of the Harvest to send forth laborers, send Shepherds into the field. I am humbled by how I am greeted on our apartment’s street: “Pastor.” “Rev.” “Park Pastor.” My favorite is “Hey, Preach.” But the one that honors me the most is when my neighbors call me, “Pastor of the Hill.” That’s crazy, right? I had just walked out of our apartment front door, heading to my car for a meeting, when I heard, “Pastor, come here.” This happens often. I do not carry cash on me. This is an important rule ministering where I pastor. Usually it is, “Do you have a dollar?” or “I need $8.50 for a bus ticket.” It’s hard, but I need to say, “No, I don’t.” Yet, I am a neighbor. And, a pastor (which most of our neighbors know) . . . so, sometimes I try to find other ways to help. This morning an older gentleman, who lives across the street (he admits his drinking problem and has a hard time walking because of his heart), pulled me in close and whispered to me, “Do you have a bag of groceries?” This is a tough one . . . I gave him my normal reply, but added, “When I get back, I’ll see what I can do to get you some food.” I located a $20 and found him still sitting where I left him. “Let’s go to the corner store and get you $20 bucks worth. No cigarettes though.” We walked slowly, stopping every 25 feet or so for him to catch his breath. Once inside the corner store . . . it was missional . . . a small crowd was there. Some teens shouted, “Hey, Pastor Chip!” I introduced myself to the others. Fist bumps all around. My older neighbor then surprised me when he started introducing me to his friends in the store, “This is my pastor.” Didn't expect that. And, he said it more than once. I held back tears. Of course, there are plenty of food resources, shelters, and food pantries in New Haven, which is my usual go-to reply. But, my presence in the neighborhood isn’t to be a social-worker or case-worker. This is a neighbor, someone I talk to regularly, and to whom I have given some street pastoral counseling—hard to just defer when, in some way, he’s one of my sheep (at least a street sheep). Plus, this man is abused by his boarding roommate, his food stamp-card taken regularly, and his landlord won’t do anything—and complaining just makes it harder on him. All this gentleman knows is his drinking, bad health, and sometimes Jesus shows up as his neighbor who also happens to be hispastor. These good people need a shepherd . . . It is no surprise that immediately after having compassion for the sheep that do not have a shepherd (9:36) and praying for the needed laborers to go harvest (9:337-38), Jesus appoints his twelve and commissions them (10:1-15). Although there is far more to this list (vv. 2-4) and their mission (vv. 5-15), I want to call attention to one thing very much related to our thread: Jesus instructs the twelve to proclaim that the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand (v. 7). Jesus calls the 12 disciples (10:1a) and gives them authority to do exactly what he has been doing (v. 1b)–exactly what they observed in following Jesus around as we have observed thus far. Now, they are to be fisher-followers by casting out demons and healing every disease and every affliction (10:1) and, so, they demonstrate that the kingdom of God is present (v. 7): Heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers, cast out demons (v. 8a). *This sermon was preached at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Concord, MA on Sunday, May 19, 2019. The full sermon maybe downloaded as a PDF (here). An audio version is also be available >> Audio version Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

II. We reveal the appearance of the Kingdom of Heaven when we extend mercy to the (physically and socially) unclean When Lisa and I had moved into our apartment, we were immediately recognized. More typically than not, it seems I can’t walk out my door without hearing, “Hey, Pastor, can I talk to you?” Or, “my friend here needs prayer.” I am immediately confronted with many that are unclean, unbathed, reek of smoke and alcohol; with those who aren’t very coherent; some who spent the night in the park, or the night selling themselves to support drug habits. This isn’t so far from the crowds whom Jesus encountered. I am confronted daily with the difference between the clean and the unclean, literally and socially. Now in Matthew 9:9, Jesus calls the tax-collector Matthew to follow him. Matthew represents half of the problem group of “tax collectors and sinners.” Immediately (v. 11) we hear many of Matthew’s tax collector buddies and sinners came and were reclining [at a supper meal] with Jesus and his disciples. This does not sit well with temple leadership. You have to remember in the social-location at that time, this all would have been very public, with neighbors and “the crowd” and the curious all peering in to the supper venue. Most likely a curious Pharisee was able to get the attention of a few disciples, pulling them out to ask: “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” (v 11). Jesus overhears the question and takes the opportunity to teach everyone: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.’ For I came not to call the righteous, but sinners” (vv. 12-13). This begins a thread of accusations from the temple-leadership against Jesus—they don’t like the nature of Jesus’ fishing.The accusation from the Pharisees, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners” is juxtaposed to Jesus explaining his mission, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick.” So, we have those who do not need a physician, meaning the accusing Pharisees and those who are sick, meaning the “tax collectors and sinners.” This is the pattern here in Matthew. Let’s be fair to Matthew. We like to read what Jesus said as “everyone is like a tax collector and we’re all sinners.” No. No. No. Leveling and equalizing this robs us of the narrative impact: I think we can agree Jesus calls Matthew—a real life tax collector—and Matthew invites his friends and entourage to have a meal with Jesus. So here we have the context and the social group meant by “tax collectors and sinners.” Tax-collectors are not only the bottom of everyone’s hate list, they are traitors of the worse kind (Israelites in the employment of Caesar). Sinners are not simply “everyone” (you know because everyone sins—although true, this is not the reference). It is not as if Jesus said, “but those who realize they are sick.” Matthew has been pretty clear that the crowd he has been ministering to and who surrounds Him is made up of all the sick, those afflicted with various diseases and pains . . .(Matthew 4:23-24): these are most assuredly in the narrative the “sinners”: The sick, the mentally unstable, the deceased, the lame. Elsewhere in the gospels, we know that sinners are outsiders (e.g., Galileans), the uneducated, those in sympathy with the Empire, those ignorant of the Law, those outside the insiders of the temple leadership and their friends and families. This is why the Pharisees are offended by Jesus. This is why they do not like the nature of his fishing. Jesus says in the same breath (Matthew 9:13): “Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.’ For I came not to call the righteous, but sinners.”Again, we tend to read this as if Jesus said, “I desire you be saved by grace and not by any works because sacrifices can’t save you.” All good (of course), but misses Jesus’ point.

We are most glad, most thankful that Jesus choses mercy over sacrifice. Looking at the surrounding miracles stories and the summaries in Matthew: Jesus chooses mercy

These are not the things and situations one chooses in that culture and social classing, if one desired to be pure (the goal of the religious elite) or to be perceived as holy (again, the temple-leadership). No. Not at all. We are, however, as fisher-followers, to live out mercy by being in the proximity of the crowd, and thus touching the unclean (literally and socially). This is following Jesus around; and this is doing what Jesus did, here we are made fishers of men, demonstrating that the kingdom of heaven has appeared. *This sermon was preached at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Concord, MA on Sunday, May 19, 2019. The full sermon maybe downloaded as a PDF (here). An audio version is also be available >> Audio version Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

As of January 1, My wife and I live in the Hill, an apartment on Carlisle Street, right next to the Park where we do our summer BBQ ministry. I’m even close enough to walk downtown to meetings and events. One evening, walking back to the apartment from an aldermen’s meeting at town hall, I found myself waiting at a cross-walk when two guys (you can tell, kind of down and out, probably homeless) decided to go, even with traffic coming. One guy had a walker. He walked slow across the intersection, so I headed out with him, telling him, “They’ll have to hit me first.” He smiled and said, “Thanks.” We made it safely, catching up with his friend. They continued to walk slow. I moved on ahead, walking down the block back to my apartment, when I saw a Dunkin Donuts and remembered I had a gift card in my wallet my mom had given me for Christmas. I stopped in to see how much it was for . . . there were no markings . . . $10 the barrister said after scanning it. I went back up the block to my two slow walking friends and said, “Do you guys like coffee?” “Yes,” one of them replied. “I have a gift card for $10—it’s yours.” “Thanks.” They smiled. “Good, we can get a sandwich, too.” I told them: “I can’t take credit for it, my mom gave it to me for a Christmas present.” “Well then, tell your mom, thanks for us.” (I did.) I gave them the card and said, “You’ll see me around. You will see the hat and the ponytail” . . . and, before I could get my name out . . . “Yea, we know. You’re the pastor of the church on Davenport. We know who you are.” How about that? Priceless. Two street, homeless guys, a few blocks from the Hill knew who I was and where our church is. This reminds me that we need to be known . . . and if I get my New Testament correctly, known for the things that indicate the presence of the Kingdom of God. This morning I’d like to bring a messagefrom a thread of passages in the Gospel of Matthew. There is a narrative thread connecting Matthew chapters 4 through 11 that we should listen to, which focuses on Jesus associating with tax collectors and sinners, the poor, the unclean, and the presence of the Kingdom of Heaven. Matthew is asking the readers: How do others know that the Kingdom of Heaven has appeared? To give you the spoiler: Matthew tells us, they can see our association with the poor, marginalized, outcasts, and unclean. This is how they know. I. We are to Follow Jesus around and repeat (what he does): We like to take small bites on the Bible, so sometimes we miss big picture things. And, this is a Big Picture Thing we need to see so we may be better readers of Matthew's Gospel and more faithful followers of Jesus. We begin in Matthew 4:19 where Jesus makes the invitation, “Follow [lit. come after] me and I will make you fishers of men.” The command is to come-after Jesus. That’s the command--follow after me, really follow me around. Most think the command is to be fishers of men—it is not, that’s the promise. We are called to follow Jesus around and he promises to make us fishers of men. By getting the following correct, we become fishers of men. So, what does it mean to follow Jesus around—Matthew tells us. Straight away, just after the call to follow Jesus, Matthew reveals what it was like to follow Jesus around. There is a divine, inspired-ness to what the Gospel writers place into the narrative . . . so right after the scene where Jesus calls us to follow him around, we have . . .

Matthew tells us: we are made fishers of men by following Jesus around—and what did he do?

What we might not realize, however, is Jesus’ first encounter afterHe finishes the Sermon . . . Matthew could have introduced a dozen different encounters, but this is the one He chooses:

This is the Sermon on the Mount realized, illustrated, fulfilled. The Monday after the Sunday Sermon as it were. Now I’m going somewhere with this, so for now remember, following Jesus is actually following Jesus around, learning to do what he did . . . now, we are to repeat . . . *This sermon was preached at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Concord, MA on Sunday, May 19, 2019. The full sermon maybe downloaded as a PDF (here). An audio version is also be available >> Audio version Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV

Sabbath Pleasure: A Day for Reflecting . . . on Justice for Our Neighbors (a Sermon on Isaiah 58)8/24/2018  Think about it: Think about all the people who had to work (income earning work) today just so you and I could keep the Sabbath. Do you hear how ironic this is? I have a confession to make: I’m not a great Sabbath-keeper. Don’t get me wrong: in 40 years as a Christian (that’s a lot of Sabbaths), I can count on my fingers the Sunday services I’ve missed. I just don’t rest a lot. I haven’t had a vacation since 2011. The language of vacation, by the way, is the language of privilege and wealth more so than of the poor and oppressed. Even our 2-day weekend is historically new, starting in 1908 at some New England mills to accommodate Jewish workers and, then, the depression (1930s) institutionalized the 2-day weekend as a way to “solve” underemployment. I rarely take a full day off. Sundays are not rest: there are hospital visits, visiting families whose loved ones have died, and visiting those in drug rehab programs, et al. And, of course, Hill birthday parties. There goes my ceasing to work. I’m more a John 9:4–We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming, when no one can work–kind of Christian. In parts of Africa, water is scarce. Women and children must travel, on foot, carrying containers, to retrieve their daily water for cooking, drinking, cleaning, and bathing. Most travel far and even up to 3-hours on foot to find water–that can be a 6+ hour journey, every day! Most of the water is not potable (not clean); it is stagnant and filled with things you’d never allow your kids to put in their mouths. I think of this when I think of church planting, building a church, Sunday worship: how do these women stop and go a day without water so their families can join church worship and affirm our confession to keep the Sabbath? So, this leads me to ask: what is our Sabbath responsibility toward the under-resourced in Bridgeport or the Hill, those working 2 to 3-jobs, car-less, food-less, shelter-less, those who need to work on Sundays . . . ? Our text, Isaiah 58, is not a pleasant one and can be seen as rather harsh. Isaiah 58 will forever be a judge of our form (institutional and local) and our religious practices (habits), reproving our intentions and reminding us, as God’s people, the gathered-church in this place, what is important, what should be assumed about our habits, and what we should be famous for. I’d like to do three things this morning:

I. The honest accusations of Isaiah 58 on Sabbath-keeping

Ok, I won’t hold back! Religion, even Christianity, including our own church-life will take on form and over time will produce institutional structures and systems. These are inevitable. We have them (if you haven’t noticed). Now, these structures and systems must be maintained. Now, we need to appoint "maintainers" and give them authority that, will eventually, put the structures and systems over people. (This is what happens; it is mostly unavoidable.) That is the nature of structure and systems. And, there is always some who will have a vested interest in these “forms” and this clouds everything up--decision-making, budgets, and all the "who" which are overlords (managers) of the “forms.” Isaiah 58 comes as Israel faced exile and here the prophet speaks against how such institutionalized religion has failed to make a difference in human relationships, especially between the haves and have nots, between those of privilege and property and those of disadvantage and land-less (that is, those with scarce-to-no resources) . . . there are more possibilities, in our institution, of acquisition of things and the stink of pride that can attach itself to maintaining our Sabbath-keeping, which can drive our Sabbath experience and church-life maintenance decisions. The prophet indicates that, although the people think their behavior should win them favor with God (look, we’re keeping Sabbath!), its real purpose was to gain prominence, power, position, and, of course, possessions. With obvious sarcasm, Isaiah chides: they seek me daily and delight to know my ways . . . they delight to draw near to God (v. 2). We can outwardly be keeping Sabbath, even justifying what we do as somehow keeping Sabbath because we are seeking God, reflecting on God and his creation.

If we take the order of Isaiah seriously, by the time we get to Isaiah 58, they have experienced the Servant’s redemption (Isaiah 53). They would have received drink and their fill of food they did not have to purchase (Isaiah 55). The foreigner and the eunuch who love God’s Sabbath would have been received into the covenant family (Isaiah 56) and those who are near and those who are far would have come to know the peace of God (Isaiah 57). So, the Israelites of Isaiah 58 have tasted the Servant’s freedom, the Servant’s deliverance. Yet, what are they doing with it? Here is the problem—the beginning and end of the poem bookend the issue:

Isaiah is clear: the Sabbath-keepers were keeping the day or rest, the fasting of work, as a day for themselves, a day for their own pleasure. The New Revised Standard Version puts it well: If you refrain from trampling the Sabbath, from pursuing your own interests on my holy day (v. 13). Rather than keeping (honoring) the Sabbath, they were actually “trampling it.” Are we, today, trampling the Sabbath because we have missed the whole point of what it was to meant to "keep" the Sabbath holy? What are we, CPC Fairfield and CPC in The Hill, doing with our freedom in Christ? Are we guilty of trampling on the Sabbath because the focus is on our own pleasure . . . on our position and status in the community . . . on some declaration of our spirituality . . . on our acquisition of processions? How do we even begin to ensure we are not guilty of fake Sabbath-keeping? II. A look back at the original Sabbath commands and how they play a part in Isaiah 58 While in the Air Force, on July 10, 1978, I received Jesus as my Lord. And, I was on fire. I hung with other Airmen who were on fire. We liked to fast. It’s in the Bible, you know. Fasting was for serious Christians. We were serious Christians. Usually just a day, skipping a few chow-hall meals, you know, to get spiritual. Then we got the bright (“spiritual”) idea of fasting for three days––three whole days. We did. And we let everyone know it, too . . . sorry, can’t go to the chow-hall, I’m fasting. Skipping lunch to read my Bible . . . I am fasting, you know, three days. When the three days were over, we met up at the chow-hall and downed a lot of food. Hey, we had just fasted for three days, you know. Some mature Christians took us aside, “Guys, that’s not how it works. If you tell people you are fasting, it’s not fasting—it’s just skipping meals.” The fasting was about us. I’m glad they had the boldness to confront the future Pastor of CPC in The Hill. It’s worth noting the original Sabbath commands. The 4th commandment to keep the Sabbath does not focus on YHWH as the first 3 words do. This command centers on the extend of those who are to keep the Sabbath. However, our institutional mind plays tricks on us, hearing Moses as if he said, we are go to church, set the whole day aside to reflect on God--that’s how we keep the Sabbath, you know, we're serious Christians! But these commands say no such thing. Based on Exodus and Deuteronomy and, here, Isaiah 58, we are to keep the Sabbath holy by ensuring that our children, our neighbors, female and male slaves, even livestock (someone’s means of work), and the non-Israelite sojourner cease to work. Nothing about worship. Nothing about going to the beach or a park or pulling up a chair in the backyard to read a Christian book and contemplate God's good creation. Nope. Not a word.

[Nothing on what we are to do, but what we are not to do—and who “the not doing” extends to.]

And just in case you missed it, Moses repeats one specific people-group:

Moses repeats that even their “male and female slave” (come on, by now you know very well the term is “slave”), making for an emphasis on all, everyone are to Sabbath, not just the blood household. All were to cease to labor on the seventh day of the week. Then to offer the reason, Moses concludes in verse 15:

Let me offer a different reading for why remembering their slavery is important as a basis (i.e., the therefore) for keeping the Sabbath: It compliments the reminder, the repeat of “male and female servant" in the extend of who was to keep Sabbath. The history lesson underscores that Israel was oppressed and forced to work. The new association with YHWH, experiencing God's freedom, His deliverance, brings something new: the Sabbath command equalizes. The rest wasn’t just for the privileged and powerful. Again, Isaiah sings with some irony and sarcasm: Is such the fast that I choose, a day for a person to humble himself? (58:5). The way it is written (and to be heard) demands the answer: No that's not what that day is for. We claim the opposite as Sabbath-keepers; we claim it is a day to humble ourselves (again, nothing in the commands that point in that direction for the Sabbath day). Remember, our Sabbath–fast (the ceasing of our labor) is not about humbling ourselves (you can hear how Sunday can be turned into PR and self-fulfillment). Here’s how Isaiah 58 corrects us and what God desires:

What are we doing to ensure all are equal and enjoy God’s rest? Isaiah 58 asks us, what are we famous for? III. A Sabbath–Fast that Ensures the Least and Lacking Among Us Experience Sabbath-rest Before returning to church ministry, I worked for 20 years as a community action grant-writer and program developer. We served the poorest of populations. One example: our population lacked good nutrition and underweight babies marked the population, but many could not get to the stores that had fresh produce (and if they could, travel back with all the groceries) nor could they afford food that was nutritious. Nothing in their neighborhoods. Bus routes didn’t reach where they lived. The system was against their well-being. As church, comfortable at our Sunday Sabbath-keeping, the very systems that allow us the privilege of a Sunday fellowship and worship might very well work against the well-being of the least of us. Isaiah 58 makes this connection for us. In Isaiah 58, fasting and Sabbath-keeping was their vision, but it was something for their own pleasure; yet, God had a different vision. Cultic behavior, systems, habits . . . may be self-indulgent . . . or [they] may [even] be magical in mentality (Muilenburg). Our Sabbath behavior can be turned into a device for making God do our will or to demonstrate how spiritual we are (sadly, a public display). If we truly want to cease (fast or Sabbath) from something, let us put a stop (a cease) to oppression. A) The equalizing intentions of the Sabbath will indicate God is in our midst Sabbath was a sign, but what did it signify? Exodus 31:13, states, “. . . you shall keep my Sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you . . . that you may know that I, the Lord, sanctify you.” The Sabbath-sign signified God was in their midst. Isaiah 58:8-9 affirms what the Sabbath-sign signifies: when the intent of the Sabbath is enacted (verses 6–7), then the presence of God among his people is apparent:

This is set as an if-then scenario: If we pour ourselves out for the hungry, then God will be seen in our midst. A small reflection of this can be illustrated by our CPC in The Hill summer park BBQ ministry, called “In His Midst.” When we go to the park, God is already there (we didn’t bring him) . . . so we are “in His midst.” And, because we are church in the park, the people in the park are “In His Midst.” B) Ensuring all have Sabbath pleasure, true rest, we will be the restorer of the streets It should not surprise us: the first marks of the church in Acts are the sharing of resources so no one had need. Have you ever wondered how believing on Jesus produced followers and gathered-churches that—knew instinctively—their possessions were to be held in common for meeting the needs of any and all, literally, house to house. Acts 2:44-45 The ascended Jesus and the outpouring of the Spirit brings about the deliverance and freedom for God's people, thus the call in Isaiah 58 becomes reality. The Isaiah 58 Sabbath rest is a call to restore the intentions behind the original Sabbath commands; this links the presence of God among his people to the flourishing of the City. So it was quite natural for God's people to be like a watered garden, like a spring of water, whose waters do not fail (v. 11b; see why I link the African water crisis to church planting) and you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to dwell in (v. 12b; and can you see why I connect the gospel to the flourishing of our neighborhood). The true mark of keeping Sabbath is to find ways to fulfil the intentions of the command: to find ways to ensure everyone, especially the marginal, oppressed, and the poor—those who lack resources—discover God’s rest and to be included in Sabbath pleasure. What is it about our “Sundays” that ensure others are “ceasing to work” and finding God’s rest . . . ? 1) First, we must ask: what is it about our institutional religion, our way of doing Sabbath that prohibits this? 2) Is our vision of Sabbath and fasting God’s vision or something that places us (places me) in the center? Something for our pleasure? 3) And finally, so, what are we famous for? May our form of church, our form of Sabbath-keeping be such that we ensure that the poor, the homeless, the hungry discover God’s rest and find Sabbath pleasure. For then, we may be called the restorer of the streets.

III. Above all this scene reminds us as a gathered-church, we are wholly at odds with Caesar and all the powers—the tables are turned The final of the three Pilate-questions that occupy our attention comes after Pilate could find no guilt in Jesus, “Shall I crucify your King?” This question sets up the statement of all adamic statements: “We have no king but Caesar!” The Jewish leaders themselves had become frustrated with Pilate and, so, had turned to the clincher of their argument for doing away with this Jesus--they made it all about Caesar. They do what the world always does: they change the characters in the judgment hall. They put Pilate before Caesar rather than Jesus before Pilate. The Jews set Pilate up, for when “Pilate sought to release him” (19:12), the Jews cried out, “If you release this man, you are not Caesar’s friend. Everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar.” And in their last breath, the words that confront us all, Pilate was done—out-done: “We have no king but Caesar!” The ironic thing, the Jewish leaders didn’t want to defile themselves by going into Caesar’s Jerusalem judgment hall, yet they had carried Caesar in their hearts, leaving them most defiled and guilty at their very core before God. As he had tracked the Jewish leaders and Pilate down to that very moment, Jesus puts every listener of this story, us all, on trial. Who is your king? But I don’t want to leave this here before the individual—which of course each of you, each of us must decide who is our king? —but I think we need to go right to the listeners of this in its original setting and see how this all works for church, for a gathered-church. This scene parallels the apostolic and early church’s social-religious-political-civil setting—as Jesus was on trial, so is the gathered-church—not just for judgment, but to affirm their allegiance, for encouragement, despite all appearances to the contrary, Jesus is king! As I said already, this scene is good news to the church!

The gospel shaped gathered-church is not simply one of social integration, but is a scandal to any human institution that systemizes tiers of human hierarchies, be it social, civic, or religious. More than simply a model, everything about the early, locally gathered-churches challenged the empire, the temple-cults, the religious and political establishment, the business world, and, supremely, all human relationships.

Celsus, the second century critic of Christianity, described the spread of Christianity as a religion of “slaves, women and little children,” a warning and an argument against the church, for it disrupted the status quo ordering of life. It was “unlikely that Celsus would have thought the Christians worth his notice had he not recognized something uniquely dangerous lurking in their gospel . . .” These gathered-churches were made up of unequals and strangers. Their gatherings were seditious and dangerous at two levels: social (the leveling of social status) and empire (another king). Their presence, like no other, threatened to destabilize all of society. It is no shock, then, that the church was scorned and persecuted. Yet, the church lived in the tension and conflict differently (than other rebellious sects and groups) . Like Jesus and his kingdom, the church will not be defended (or grow) by the world’s means. By any form of violence or appeal to power. Yet, we turn too often to the powers to get our way, to defend our plot of ground, to promote our agenda—way too close to the duplicitous Jewish leaders’ use of Caesar’s power through Pilate. The very opposite of Jesus before Pilate. The Ephesus church would later hear from the Apostle Paul that the gathered-church's fight is not against blood and flesh, but against the spiritual powers in the heavenly places (6:12) . . . our struggle is always to keep Jesus before our accusers and we must stop making our gospel, our stake of ground, our values a fight between our neighbors and Caesar.

You see, this cup would have been raised throughout the Roman Empire at this time, at every household supper gathering (an evening household banquet, if you will) . . . this is where the church would have declared openly, in front of each other and guests and onlookers (remember, the uninvited would crowd around these suppers to see what's happening)—this is where they would risk everything, set things right, and declare that they had no king but Jesus!

[1] David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 167. *This message was originally delivered at Christ Presbyterian Church Fairfield and Christ Presbyterian Church in The Hill.

II. This scene tells us we serve another king and is the gospel to us, the church The second of our Pilate-questions comes to us in v. 33, “Are you the King of the Jews?, and suggests that Jesus is no ordinary accused. This question sets us (the listeners of the story) up to realize we belong to another kingdom and serve another kind of king, that our belief and church habits should affirm this in our gathering and in our discipleship, in how we do church. As Paul pulled from an early liturgy in Phil 2 (And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross, 8) and certainly his the “Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed” (1 Cor 11:23), the church early on began to remember the events associated with what we call Passion Week. Some of the earliest Christian art portrayed the scenes in this episode of Jesus before Pilate, an indication of their importance in the habit and devotional life of the early church . . . “that which we have seen with our eyes and our hands have handled,” later John tells us—and then we have the creedal, “He suffered under Pontius Pilate.” God died–not in legend, not symbolically, not in a distant past, not in some mysterious realm. The gospel story is brought down to earth and made a part of the life of the church, a part of the life of a gathered-church. Each Sunday Christians everywhere make as part of their confession two names: Mary and Pontius Pilate. Mary’s name as part of Christian creeds is no surprise, but something should jar us about the inclusion of Pilate into the church’s liturgical memory. Karl Barth once said that running into Pilate’s name in creedal recitation was akin to the movement of “a dog into a nice room.” This scene in John’s Gospel has been etched into the memory and habits of the church for centuries. We hear it in the Apostles Creed:

What I find interesting is that the Pilate-Jesus scenes are a part of early household baptisms. Before we moved from gathered-household churches scattered across the empire to Caesar-sanctioned buildings, we have an account of a baptismal service from Hippolytus of Rome (about 200 AD): The candidate to be baptized would be asked: “Do you believe in God, the Father Almighty?” The baptismal candidate was to say: “I believe.” Then just as the rite of baptism took place, the one being baptized was asked: “Do you believe in Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who was born of the Virgin Mary, and was [wait for it . . .] crucified under Pontius Pilate . . .” Christians began their life of faith with a confessional connection to Pontius Pilate. Later in the Nicean Creed, about 325 AD we read (we recite), “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven . . . For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate.” For our sake . . . the initiation and weekly confession of our faith was linked to . . . Pilate and Jesus We don’t know much about Pilate. We know that he was a Roman prefect over Judea and we know that he was married. Dorothy Sayers wrote: the importance of Christ before Pilate is that we no longer behold God-in-his-thusness, as transcendent, abstract, and universal, but rather God-in-his-thisness, as embodied in the person of Jesus, as immanent, concrete, now encountered as triune. Indeed, we are face-to-face with the shocking particularity of the Christian faith, made more scandalous by God’s weakness and poverty in the person of Jesus. Sayers reminds us that the threats of those in power mean nothing to those prepared to die, to those who know that dying and suffering is not the worst thing we do as human beings. The truth rests with those who, in humility, are not afraid because they know what is beyond this life–they know a different king and belong to a different kingdom. In this confrontation between Jesus and Pilate, the battle between the powers of this world and divine power comes to a pen-ultimate climax, with Jesus acknowledging Pilate’s limited culpability when Christ tells him “You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above.” Pilate’s question in 18:39, ‘What is truth,’ exposes the perplexity of a person who is a stranger to himself, uncomprehending and confused, so very short of the freedom proper to human life (Sayers). But this is the same space the church occupies amid outsiders, for we know the truth. There is narrative parallel here between Jesus’ kingly authority and the mention of truth. In his Gospel, John closely webs Jesus’ presence and authority to the concept of truth:

And in our scene this morning (v. 37): “. . . for this purpose (Jesus says to Pilate) I have come into the world—to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth listens to my voice.” It is here that the Accused calls his judge to repentance and to choose what does not appear to be the case in that judgement hall. Jesus opens a path to faith for Pilate to believe Jesus is a king and has kingly authority: choose Christ or choose Caesar. The One in the dock (the old English word for the place of the accused in a courtroom) invites his judge to be his follower, to align himself with those who are “of the truth,” to deny Caesar. In this Jesus is very dangerous to all who have power. Isn’t this our calling? Isn’t this the church, a local gathered-church, set at the end of accusation . . . calling our accusers (the skeptical, the unbeliever, those that misunderstand us, those that judge us fools and foolish) to join us, to deny Caesar and all the powers aligned against God and to follow the One who went to a cross because that is the only way for life to happen, the only path of resistance to the powers of this world.

Isn’t this the sphere and place of church: we confront our accusers (outsiders on that wide range of skeptics to haters) in our worship and in our mixed gathering of unequal strangers with the presence of Christ, to create an opportune space to acknowledge Jesus as king? The tables are turned in a gathered-church. It is our very presence, it is the witness of the very presence of the church, as it stands before Pilate if you will, before our neighbors, family, and friends, that opens the choice: choose Caesar or choose Christ . . . And for us, right here, right now: If Jesus’ claims are to be believed and investment in the church is to be had, despite social, political, religious, and familia pressures to abandon or compromise, then the nature of Jesus’ authority, the nature of his kingship need to be clear—at the most critical moment, right here before Pilate (when life or death is the apparent choice) it is made very clear. This claim, the fledgling, persecuted, maligned, powerless church needed to hear, just as we do as a gathered-church right here: Life nor salvation would not be found in the temples that Caesar used to maintain his control over his empire; but, in the One standing before Caesar’s proxy—life and salvation is only found in the One who suffered under Pontus Pilate. Even this awful scene, despite all appearances, is gospel especially to a gathered- church.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is one the most influential novels in American history. I betcha didn’t know it has a subtitle: Or, Life Among the Lowly. Released in 1852, second best-selling book of that century only to the Bible. Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicted the reality of slavery, and, to some, helped to lay “the groundwork for the Civil War”[1] A southerner reported saying that this novel “had given birth to a horror against slavery in the Northern mind which all the politicians could never have created” (David S. Reynolds). Even Abraham Lincoln, upon meeting Harriet Stowe, famously said, Is this the little woman who made this great war? I love to tell stories. My daughter says, “Dad, you have a story for everything.” She didn’t say I had lots of stories, but for everything I had a story. Stories are for the hearer—they do something for those who listen. Just like Uncle Tom’s Cabin had unleashed “this great war” to help end slavery, so the Gospels are for changing us, motivating us, the gathered-church . . . no wonder God created the “Gospels” to immortalize His story to his gathered-churches. I’m persuaded the Gospel of John was written in Ephesus and its audience was the household churches throughout western Asia Minor. These house gathered-churches were filled with believers who had had a very cultural, pagan temple-life, centered around the Roman empire, the Caesar-cult, and multiple deities, regional, local, and even household amulets; and, who celebrated this life at regular “suppers” of gathered guests and peers (known as diapnon). I know Pastor Andrew has drawn out the temple themes in John’s Gospel—and this should be no surprise, for as the gospel had so disturbingly penetrated the Gentile world and now . . . believing Gentiles and households of worshipping believers needed to learn a different temple-life. One that looked and felt more like a living room filled with unequal strangers . . . one that was treasonous to Caesar and the empire rather than one socially and culturally safe and approved by Caesar—or, like now, safe in a Christianized culture. What would this episode in John 18-19 mean to those young household churches of mostly former (and some, for sure, still) temple-worshipping Gentiles; of families empire-dependent and encultured by pagan temple-life? In some way, this switch from going to temple and living a temple-habit life, in and out of one’s home, has some bearing on how we are to hear this epic set of scenes in John’s Gospel of Jesus before Pilate. The question before us in this episode isn’t just historical (e.g., nice things to know about Jesus), but how does it speak to us as church? Not insights for our privatized Christian lives, but a story for church, a gathered-church, for Christ Presbyterian Church Fairfield or Christ Presbyterian Church in The Hill. As with any story, we should ask with whom do we identify? We’d be splitting hairs over identifying with the Jewish leaders or the crowd or with Pilate. Let’s not say Jesus . . . not this time. As with the nature and purpose of the Gospels, I say, it is the readers with whom we are to identify: what does this text mean for those early Christians and what is its significance to us, the gathered-church right here, right now? There are lots of questions Pilate asks throughout this scene. John harnesses them as platforms for the listening gathered-church to hear and respond themselves to this story . . . there are three questions in particular that help us through this scene so we may respond as church. I. This scene orients us toward fulfillment—it calls the church to have patient-trust in God’s fully capable providence The first of our Pilate-questions comes at the scene’s beginning, verse 20: “What accusation do you bring against this man?” Though Pilate is asking the Jewish leaders to determine if Jesus should be before him in the first place, this question sets up the listener to learn that Jesus, despite all appearances, was before Pilate because God had put him there. John records for us in 18:31-32 Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law.” The Jews said to him, “It is not lawful for us to put anyone to death.” This was to fulfill the word that Jesus had spoken to show by what kind of death he was going to die. Later, in 19:10-11, after the Jews challenged Pilate’s authority, which made him fear, we hear Pilate demand of Jesus: “You will not speak to me? Do you not know that I have authority to release you and authority to crucify you?” Jesus answered him, “You would have no authority over me at all unless it had been given you from above . . .” In this, we should detect the plan of God. Jesus is right where God put him. The opening scene links the Jewish temple-leadership and the Roman imperial power together (18:28–32). After Jesus’ arrest, he is led from the house of Caiaphas, who was High Priest, to the governor’s headquarters to get Pilate to exam him. Although Pilate was a weak regent for Caesar in Judea, with him there, Caesar was there in that judgment hall nonetheless. And, despite appearances, the presence of Jesus was confronting temples and temple-powers. Yet, we should also note well the hypocrisy of the temple-leadership exposed here: “. . . They themselves did not enter the governor’s headquarters, so that they would not be defiled, but could eat the Passover” (v. 28) They are willing to use the power of Caesar to do their dirty work in doing away with this troublemaker to their own established authority. Yet they didn’t want to touch the heathen plot of ground—they didn’t want to appear polluted, contaminated and so be denied the Passover. This is significant in that they knew full well that turning Jesus over to Pilate and in short order making it all about Caesar’s authority was to condemn Jesus to crucifixion. The irony: manipulating the political system to kill off the true Passover—1 Cor 5:7, Christ our Passover has been sacrificed. Here, too, we should detect the plan of God.

The first Christian book to be penned by an early church leader, the very first, do you know what the subject was? Tertullian penned Of Patience about 207AD. But when the Lord says this about the flesh, pronouncing it “weak,” He shows what need there is of strengthening, it—that is by patience—to meet every preparation for subverting or punishing faith; that it may bear with all constancy stripes, fire, cross, beasts, sword; all which prophets and apostles, by enduring, conquered! (Chapter XIII) A second general Christian volume comes to us from Cyprian of Carthage at about 257 AD. Guess it’s subject? The Advantage of Patience. What is so fascinating is that Cyprian linked patience to that scene in John’s Gospel of Jesus and Pilate: Surely, He who was not rebellious, neither contradicted, when He offered His back to stripes, and His cheeks to the palms of the hands; neither turned away His face from the foulness of spitting. Surely it is He who, when He was accused by the priests and elders, answered nothing, and, to the wonder of Pilate, kept a most patient silence. . . (No. 23) This is the first thing: As a church we need, despite all appearances, to have a patience-trust in God’s providence. Imagine the trust and patience that they needed . . . no leverage, no power, disconnected from everything that gave life meaning (no temple, no protection from honoring Caesar, no affirming the tiers of human-hierarchy that sustained the life of the empire), nothing but their fellowship of unequal strangers, somewhat unlawfully meeting in someone’s home . . . Jesus standing there at the end of Pilate’s (really Caesar’s) judgment . . . we, too, must have such patient-trust that we are right where God has put us as a church

I am working on and preparing for Sunday's sermon (2/25/18)–one of the hardest passages in the NT, 1 Peter 3:18-22. Nonetheless, there is, in this tough, baffling text, the secret, the mystery for how the early church changed things and how it, with no power or leverage or prestige scared the living day-lights out of Caesars and the Roman empire–and still, today, can change things now . . . here's a preview . . . and some basic, preliminary thoughts . . . First, let's stick with what is clear from this most enigmatic of NT texts:

And, then, second, this text is good news to the church, to believers in that . . .

It is amazing that this small, embattled church made up of unequals and strangers, should have scared or alarmed anyone, especially those in power. Yet, it did. We, today, are quite harmless–this is perhaps why so many Christian social justice advocates and, as well, Christian conservatives rely on the government (i.e., earthy power) to do justice and enforce (always through some form of violence and/or punishment related actions) justice. I believe our lose of the power God gives his church, his local gathered-church has been lost because we hate the idea of suffering (like Jesus) and so want the acceptance and comfort our earthly powers grants us–as individual believers and as local gathered-churches. Here is my thought on the significance of this text in 1 Peter. And by "in," I mean in the flow and thought of Peter's Letter to the "elect exiles of the dispersion in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia" (1:1b):

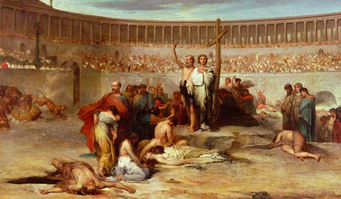

I must make two confessions up front as I began reading through the much treasured, but very often misunderstood John 13 footwashing scene of Jesus and his disciples: First, the eighteen plus years as a planner-grant writer, program developer, and instructor in the social action field, working for agencies that help the poor and low-come, has made me more aware of the Bible’s overwhelming connection to the poor. I most definitely read the Bible differently now. I can see more clearly what I have passed over, spiritualized, and, too often, ignored. I now pick up on nuances in biblical texts and stories that were blurred by my suburban, more privileged up-bringing and how my early Christian years were shaped. I confess am no longer a poor rich reader of the Bible. Second, and with a deep breath, I confess I am burdened and terrified by the call to minister in the Hill community in New Haven, Connecticut. I awake with burdens beyond what I could have imagined as I seek to minister in this broken, yet beautiful community called The Hill. Frankly (and some tell me, don’t let them know how you really feel, don’t show weakness), I am scared to death, sometimes awakening and wondering, “What in the world have I gotten myself and my wife into here?” Scared I’ll mess it up. Frightened that my vulnerabilities will be seen. Afraid my shortcomings, my age, may exhaustion, my weaknesses, and inabilities will be too soon noticed. Yet as Paul heard from God, I too rest in the words, “‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me . . . For when I am weak, then I am strong.” So, with humility I approach the text, weak and a common sinner in the hands of an all-too-gracious heavenly Father . . . and you, with so many reasons to listen to others, but with hopes you will hear the text. Let us pray . . . Let’s time travel back to the first few hundred years of church history. Most of us are familiar with the Greco-Roman colosseums and the brutality of the gladiatorial entertainment in the days of the Roman empire. In those colosseums there was a theater of real, unashamed, and intentional death that was designed to displayed the vertical nature of society, of social order, who had status and who did not—and who was and wasn’t a person. Why do I start here? The arena of death and violence is, you must understand, still the experience of so many around the globe today and in most urban centers in the US and in The Hill community—designed by default and intention, in our very built environment—continues to affirm social vertical status and, dare I say, what we affirm as human. Yet, Jesus and the gospel itself point to a leveling . . . displayed in and through and by the church . . . John 13 will paint this picture for us. Religion in the Roman empire was widespread, huge, and multiple. And yet, no one would have imagined that by the early 4th century Christianity would become a major world religion with adherents numbering among the most significance slice of the empire’s population. But the church didn’t start out that way: the first small congregations had no power, no leverage of status, no influence, and certainly no money. So how? As we read through the early church literature and church fathers, one would look in vain for references specifically to “evangelism” as a verbal witness as a matter of the Christian and church life . . . in fact “speaking” would have probably done nothing and no one would have listened (anyway). Literally in the first few hundred years, Christian literature makes no reference to “evangelists” and or even “missionaries.” So, how? Back to the arena games, say around AD 203: The colosseum-amphitheater was a wonder of Roman engineering. Everything about the architecture and the events were to show off the vertical nature of life and social standing in the Empire . . . vertical . . . higher sections . . . seated by wealth and influence . . . how the stands were filled . . . the upper sections were the visual center . . . magistrates, landowners, benefactors, the elite . . . the entertainment of the populace to bolster status and prestige—all affirming the vertical values of society and civil life. All the while, who were in the death-pits, the forced entertainment of death at the bottom of the arena? Of course the gladiators and lions, but it was the bottom of society that faced death—criminals, the unwanted, slaves, the abandoned—all for sport and entertainment. There we also find small bands of Christians . . . but they faced death (face the beasts and gladiators) differently; their presence in the arena subtly subverted the carefully choreographed vertical event. The masses saw husbands (the paterfamilias, head of households), wives, slaves, doctors, former prostitutes, unwanted children standing together . . . expressing publically right there in the arena Christian horizontality. (Yes, that is a word.) When one would fall, the others would help them up to face death standing. They did not defend themselves in any way. Although the whole of the gospel and NT teaching is behind their behavior, but it is the fact that Jesus left a footwashing community and not a militia or even an academy to invade this world IS THE HOW Christianity grew to overtake an empire. Here in John 13 we have a portrait, along with Jesus’s words, a powerful image and reminder of what the Christian community is to look like in the private habits of our worship and out in the public, in Caesar’s arena of death. The cliché is an easy one: Jesus had to leave, but he left a community. The harder thing: John leaves a community of footwashers to show his love to a watching public world: Jesus’ presence in the world is displayed by a mutually loving church that demonstrates the leveling of humanity, the horizontality of God’s love. Our focus is John 13:33–35—and how these verses stand in the midst of the footwashing scene, surrounded by a traitor among them (Judas) and Peter’s brash, impatient display of allegiance. Little children, yet a little while I am with you. You will seek me, and just as I said to the Jews, so now I also say to you, ‘Where I am going you cannot come.’ A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another: just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another. By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:33–35). Everything seems driven by these words from our Lord, here in chapter 13 and all through John 13-17. So we will center on these verses through the footwashing and the outer bookends texts about Judas and Peter in John’s narrative. I. Setting the stage with the footwashing example–Jesus prepares his new community for his departure II. The juxtaposition: The Traitor (Judas) and Brash, Impatient Denier (Peter) III. The power and habits of our text: The Presence of Jesus is the loving-one-another church–the visible, tangible leveling power of the gospel For the full sermon text, please click the download file below . . .

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed