Sermon prep for and thoughts from my study of the last half of Luke's Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6) . . . Church, imagine a trafficked woman and one who used to enslave women sitting at that Table, after breaking bread, having a supper, and after lifting that fourth cup together to celebrate Jesus as Savior and King . . . imagine a beggar and a wealthy man . . . imagine a wife and her husband, who'd normally have been found with a temple prostitute or at a similar supper using women as entertainment . . . imagine young boys and men who had, until recently, frequented similar suppers where such young boys were entertainment . . . imagine . . . imagine the early church gathered at that Table now ready to listen to someone read the parchments containing Luke's Gospel . . . imagine . . . Imagine hearing the Sermon on the Plain being read (Luke 6:20-49) . . . imagine they all hear, not only the blessings on the poor and the cursing on the rich (vv. 20-26), but hear “love your enemies,” “do good to those who hate you,” “pray for those who abuse you” (vv. 27--29). . . “do not judge” . . . “do not condemn” . . . “forgive to be forgiven” (v. 37) . . . and “give and lend without regard to getting anything in return” nor “demand back what was taken” (vv. 35, 38) . . . imagine those who were around those first Tables, not only hearing these words, but doing them . . . Sometimes I think we have it way too easy at this church stuff and that has dulled our hearing . . . and flattened our doing . . . and it is no wonder our houses crash when those winds come . . . it is not enough to be hearing His word and, frankly, it is not enough just to do the word where it is easy and socially and culturally safe. Other Luke 6 Sermon on the Plain thoughts . . .

0 Comments

First a sermon illustration to start us off: There is an old illustration of Hell that still speaks and I think it sets up my point from Luke 6:37-49: Hell is like a long banquet table with all sorts of food and delights, but everyone at that table is getting thiner, more gaunt, more haggard from hunger. They are starving with all that food before them. You see, the utensils they were given and had to use were six foot long chopsticks. If they’d only thought unselfishly and fed each other, no one would be starving and all would be enjoying the great banquet. Thus, the Adamic nature of the human-being and why the existence of Hell. Now, the point of the illustration, here, is the audience of Luke’s Gospel, the listeners/readers before the text, that is, those house-churches (associated with Theophilus) with believers sitting around those tables enjoying a meal (aka breaking bread) and lifting that fourth cup of wine at the end of the supper, celebrating together and acknowledging that Jesus is Savior and King. And us, now . . . Still, for now, imagine those tables with former enemies and individuals of clashing social status all confessing Jesus is Lord, a new fellowship of unequals and strangers. Love your enemies and stop judging makes applicable, narrative sense (Luke 6:27, 37). It makes church sense. So, let’s take a look at the text and context, beginning with Luke 6:37-38a: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive, and you will be forgiven; give, and it will be given to you” What do we have here? There is an obvious structure that helps us read it properly:

This whole pericope (i.e., set of commands) should be taken as one thing. Yet, still there are questions begged to be asked . . . ➤ Stop judging what? And, what will we be not judged of? ➤ Stop condemning what? And, what will we be not condemned of? ➤ Forgive [others] of what? And, what will we be forgiven of? These are all left open-ended, unanswered by the command and promise. Most supply don’t judge sin in others and sin will not be judged of you . . . forgive others of sin and sin will be forgiven you. We might infer this, but the sentences do not demand or necessarily imply this reading. Now, the last command . . . ➤ But . . . the “give” is already in the context and, thus, can be applied to the whole: “Give to everyone who begs [“borrows” is a far better reading] from you, and from one who takes away your goods do not demand them back” (Luke 6:30); “And if you lend to those from whom you expect to receive, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, to get back the same amount. But love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return . . .” (vv. 34-35). So, how does this help us with reading and applying this element of the Sermon on the Plain? Pretty much most see the judging and condemning related, as I mentioned, to sin--you know, don’t judge the sins in others (i.e., the specs) before you deal with the sins in you (i.e., the logs/beams). Nothing in the text nor the context warrants this reading. However, something else is within range. Let me suggest: there is a social and cultural association/relationship implied that I believe we can reasonably and appropriately infer. We have the “poor” and the “rich” already referenced in the Beatitudes (vv. 20-26) and there are the references to “enemies” (v. 27b), “those who hate you” (v. 27c), “those who curse you” (v. 28b), “those who abuse you” (v. 28b), “the one who strikes you on the cheek” (v. 29a) and “the one who takes away your cloak” (v. 29b), including “the one who begs from you” (v. 30a) and the “one who takes away from you” (v. 30b), and, especially, there is the patronage giving-lending-for-return (vv. 32-35)–all pointing to social and cultural castes of relationships (very much the poor/rich referents mentioned in the Beatitudes). . . this “giving” et al. idea is drawn into this set of instructions (as already pointed out above), which, based on how the instructions is structured, infers to the whole (all of the commands). Simply: stop judging-stop-condemning-start forgiving-start giving is an extension of “love your enemies . . . do good to those who hate you, which leads to the give/lend expecting nothing in return.” Seriously, this reading actually solves the “poor” and the “rich” referents . . . and supplies how it is the “poor” and the “rich” are now breaking bread together as members of the family of God (around those tables). There is a social and cultural shift amid the new community of God in Christ Jesus around those tables—something both attitudinally (i.e., renewed in mind) and concretely (i.e., a behavior, a lifestyle that is) different, wholly distinctive about this community of Jesus followers. There is something missionally different (and imperative) and something intrinsically different (relationally), even something ontologically unalike the social and cultural milieu (the social location, what makes the empire adhere and maintain, the tiers of human hierarchy) that surrounds the church–these congregations, these tables, these local, neighborhood house-churches are a new creation, unlike anything else now or before. Missionally important because this redemption in Christ is for all people—using Paul’s language in Romans 1, for the elite-Greek, barbarian, Jew, educated and uneducated; using Luke’s (i.e., Jesus’) the poor and the rich, the beggar/borrower and the lender. The message itself (i.e., the gospel), those to whom the message was to be shared (missional importance), and the new relationships at those tables need to match, align. Thus, enemies are also to be loved—out-there among those to whom this gospel would offend and threaten, these cultural enemies. First, all made visible at those tables of gathered Jesus followers (i.e., disciples). And, made outwardly relevant by doing the same among neighbors and in the community. Can’t reach and minister to those whom you are judging and condemning—and I take this to mean socially and culturally judging and condemning (given the narrative context) . . . and as such among the socially and culturally unacceptable* (read both ways—poor to rich, rich to poor) that we are to love, do good, forgive, lend, give) . . . and this gospel is made visible and real around those tables throughout the local house-churches. It seems, given the diversity at those tables and the new rules (if you will) of who can and should be at the table, there would indeed be a need to stop judging/condemning and a whole lot of forgiveness to go around and new patterns of giving to be had. There is no privilege (or patronage) at that table. There is no cursed at that table. Only new relationships in Christ. Given that the Sermon on the Plain ends with the house parable, which speaks to the actual house-church-settings (Paul uses the same in Ephesians 2) and is about discipleship, specially listening to (meaning, obeying) Jesus’ words—those who hear and does them—what I have proposed here seems a good, reasonable (exegetically, narratively, and contextually) faithful reading of the Luke text regarding “judging” et al. And, thus easily and significantly applied to our own church fellowships and witness (mission). *socially and culturally unacceptable are those in castes that are despised, shunned, hated, outside blood-lines, social groups, vocationally loathed, economically reviled, and religiously held in contempt (of which the Christians because of whom they follow and because of this new socially destructive teaching would also find themselves)--this can, nonetheless, be applied (i.e., done) reciprocally from one group/caste to the other and visa versa. Other Sermon on the Plain Wasted Blog thoughts

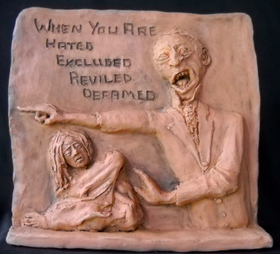

Wasted Rough Cut: Listening to Jesus' Beatitudes (in Luke) and not robbing the poor of their power.1/16/2022 *The following is a set of sermon prep-notes and ideas for my sermon on Jesus' Beatitudes as Luke presents them in his Gospel.  I am amazed, and saddened as well, the lengths Christians, even commentators, will go to read out the “poor” in a vast majority of Bible texts that are so clear and should be necessarily inferred as actual poor. This robs this text in Luke 6 of its gospel-transforming-power, especially with regard to Jesus’ words in the Beatitudes. In Luke 6:20b we read, “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” (Below I offer my own translation of this verse.) One would think a learned degree is not necessary to hear Luke sets Jesus’ reference to the “poor” in contrast to his equally disturbing reference to the “rich” in what is obviously a paralleled statement in Luke 6:24: “But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.” In fact, it is much harder to spiritualize Jesus’ reference to the “rich” than it is his reference to the “poor.” This can be seen by the fact hardly anyone does. Luke’s Gospel is filled with such contrasting of the poor and the rich in Jesus’ teachings and in forthcoming parables that we cannot escape something about actual “rich” and actual “poor” is afoot. For example, in Luke 16:20, Jesus compares the poor beggar with the rich man who disregards the beggar only to discover the poor beggar is the one who is blessed in heaven while he was filled (satisfied) on earth: “but now he [the poor beggar] is comforted here [after death], and you [the rich man] are in anguish [after death]” (16:25b). Certainly, given the wider narrative context, there is a link (i.e., a clear and necessary inference) between the “Blessed are . .” and the “But woe to you . . .” contrasted sets in the Luke 6 Beatitudes. This poor/rich contrast is also seen in Luke 21:2, when Luke/Jesus refers to a “poor widow” in contrast to the rich and the pompous pharisees. Later, in Luke 7:22, the proof that Jesus is the messiah and that the kingdom of God had arrived is given by observing what was happening in Jesus’ ministry: “And he answered them, ‘Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, the poor have good news preached to them.’” Again, in Jesus’ parable of the great feast in Luke 14, the rich are instructed to not invited those who can repay, but invite the poor who cannot repay–again, here is that link to the Luke 6 Beatitudes. (There is also a narrative link to the forthcoming poor beggar/rich man scene in Luke 16 as well.) “But when you give a feast, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the just” (Luke 14:13). Even when the context and the clear narrative meaning of the text is referencing the actual poor there is a tendency to read out the poor and read in anyone who is “poor of heart.” That certainly keeps the rich satisfied and the poor, well, still poor. This disallows the obvious social/institutional system-contrast Luke has already set up for us in his introduction, that is Mary’s song: he has brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty (Luke 1:52-53). Thus, restoring the gospel-transforming-power we have robbed from the Beatitudes by reading out the poor from this text.  Luke 6:20b: Μακάριοι οἱ πτωχοί, ὅτι ὑμετέρα ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ. ESV: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” My wooden translation: “Flourishing*, the poor (the marginal and powerless), because allotted to you** is the kingdom of God.” Smoothed out: “Flourishing is the marginal and powerless, because to you—the marginal and powerless—is allotted the Kingdom of God.” I try to pay attention to how early church writers render texts of Scripture. Tertullian (155 AD–220 AD) gave Luke 6:20 and this Beatitude the latin beati mendici—“Blessed are the needy,” or “Blessed are the beggars.” He is not the only one who translated the word πτωχοί as “beggar.” While it (i.e., “πτωχοί,” poor) can and probably does simply mean the “poor” (its detonated meaning), its connotative meaning gives a more powerful nuance. For example: The word we translate “poor,” πτωχοί is vivid: one who crouches (as in shamed to be seen) and cringes (as in cowering in the presence of others), thus it is often used of “beggars.” No doubt it carries the concrete reference to someone who is needy, someone who has no power, someone we typically call “marginal” and powerless in society, and in the ancient world one who would have been called “not-or sub-human.” The two times Luke uses this word associated with a particular person are the beggar named Lazarus (being contrasted with the rich man who had everything and disregarded Lazarus, 16:20) and the poor widow vs. the rich/the duplicitous scribes (21:2)—can’t you see what Luke is doing between the Beatitude promise/affirmations and the wider story in his Gospel narrative? There are more of these throughout the Gospel (see chapter 14 for example). The word we typically render the “poor” (πτωχοί) is better understood by how it is used. While it is certainly can be used metaphorically to mean humble,*** or as a Christian virtue, or still better, more simply, as not-arrogant, there is a reason why this word can be used this way. The word has a concrete meaning range of someone without economic means, who is marginal and powerless–again, this is why the word “beggar” isn’t a stretch and certainly fits Luke’s other uses of the word throughout his Gospel. And, it also fits the extremes of the power/powerlessness contrasts that Luke uses to describe the arrival of Messiah and the teachings/parables Jesus uses throughout Luke’s Gospel: beggar (the least and the most without power) vs. the rich (or the mighty, those who have the resources but do not share with the poor, and/or those who do only to/for those who can pay back). You can see how Luke has shaped his Gospel and why it seems a necessary inference to take “the poor” in the Beatitude as exactly that, the poor as in the marginal and powerless. *”Flourishing” is a far better translation for Μακάριοι than either “blessed” or “happy.” **The “you” is a bigger word than the simple pronoun σύ (you), but as you can see is the word ὑμετέρα, which carries the idea of “allotted to you” or “possessed by you.” Split hairs which nuance, but since this is God’s action or promise I lean toward the nuance of “allotted.” ***In the Greek world, the nuanced meaning of “humble” or as a Christian virtue is a much later connotative meaning given this word, πτωχοί, and should not be read back in to how Luke is using the “poor” / “rich” contrast and comparison.  “Blessed are you when people hate you and when they exclude you and revile you and spurn your name as evil, on account of the Son of Man!” (Luke 6:22). While I agree these words are directed at disciples, who will become Jesus’ representatives (probably the meaning behind “on account of the Son of Man,” v. 22e), the description here plays double-duty. Obviously (because we have the whole of the NT to give us fuller understanding) just because one is “poor” or “hungry” or weeping (probably all three is one group), this does not mean they do not need to be born again or qualifies them as automatically born again (something that needs to happen in order for sins to be forgiven, be justified before God, and gain eternal life). Nonetheless, it should be pointed out that “crowd” who came for healing and exorcism would not have been the ones honored nor socially accepted in either the Greco-Roman world nor the Jewish world for that matter. They'd have been the truly marginalized, rejected, and considered sub-human. “. . . a great multitude of people from all Judea and Jerusalem and the seacoast of Tyre and Sidon, who came to hear him and to be healed of their diseases. And those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured” (Luke 6:17c–18). They would have too easily identified with being hated, being excluded (separated, marginalized, rejected, avoided, ostracize), being reviled, and shunned. The dirty, shameful words trigger: diseased and possessed of unclean spirits. This was their lot, their place in the social castes and institutional systems of the world. The “apostles” that were just chosen (6:13-16), along with the “great crowd of his disciples” (v. 17b), whom the sermon is directed (v. 20), while the larger crowd was listening in—the teaching was very public (and outdoors I might point out!)—they would be as marginalized as the ones who came for healing and who troubled with unclean spirits. Jesus’ appointed representatives (the apostles) and followers (the wider crowd of disciples) would be the poor, the hungry, and those weeping—everything would be turned on its head and the world, its social structure and institutions would hate, marginalize, revile, and spurn those who were truly the blessed, that is the apostles and disciples of Jesus who followed Him and proclaimed this teaching—all on account of being the representatives of the Son of Man, those whom Jesus was reproducing Himself in the world. Yet it would be to them the kingdom belongs, their stomachs would be full (satisfied), and fulled with joy. The appearance of Messiah Jesus and the proclamation of the Gospel—as Jesus’ inaugural sermon indicated (Luke 4:18-19; cf. Isaiah 61:1-2 and 58:6-7)—changes everything about how the systems and structures of this world work (cf. Luke 1:51-53). This is what the beatitudes indicate and mean–and how they should be applied. However, we have traded this all away by making the church (and by that I mean churches and their institutionalized systems) reproduce the world in everything from measures of success to leadership and training to evangelism and (sadly) in our ways of doing and measuring being missional. Discipleship, too often, mimics how the world works rather than what the Beatitudes display.  Lastly, discipleship is not one size fits all. The way Luke has presented Jesus’ Beatitudes is more to expose the structural and systemic, institutionalized empire (Rome-centered, adamic natured) way of defining who is and who is not blessed, who is and who is not honored, who is and who is not fully (or at all) human. What divides humanity. And, addresses the danger of using the world’s way of addressing the issues of poverty and affluence. Take the poor out of Jesus’ reference to the poor and this is lost. This–that is, the Beatitudes are not about “salvation” (that is getting into the Kingdom of God), but about what the new community of God looks like, how it’s system, if you will, works. And this means applying discipleship somewhat (not entirely, but in some specifics) differently to rich disciples and poor disciples. The way to blessing (i.e., kingdom flourishing) is not the way of the world–it is a wholly other way (or as the title of a book I am reading puts it, not the way of the dragon, but the way of the Lamb). Christianity, that is our faith in Christ and our relationship to the church, is not a pathway to success (that is being one of the “rich”). And, our present power granted to us by our place or status in the social structure and current institutions no longer defines us and our neighbors. If one is among the “rich” one best rethink their relationship to the poor and adjust appropriately. Other Sermon on the Plain Wasted Blog thoughts

An article, “To the Poor, Poverty is More Than Material,” posted on the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics's website lifted an excerpt from a multiauthor volume called For the Least of These: A Biblical Answer to Poverty. The lengthy quote comes from Peter Greer's essay, “A Call to Compassionately Move Beyond Charity.” I was impressed by the reflection on how the poor view themselves and it reminded me of Matthew's “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (5:3). So many take Matthew's reference more broadly to mean those who have a good attitutde and recognize their “poverty” before God. You know, individuals who are humble and not arrogant. These interpretors make a difference between Luke's simple “Blessed are you who are poor" (6:20) and Matthew's “poor in spirit.” However, this is a rationalized, poor rich reading of Scripture that basically strips the poor out of “poor in spirit.” The excerpt from Peter Greer's essay gives us a basis for understanding that living in poverty is more than just a material matter and reminds us that the poor are indeed poor in spirit. In the 1990s, World Bank surveyed over sixty thousand of the financially poor throughout the developing world and how they described poverty. The poor did not focus on their material need; rather, they alluded to social and psychological aspects of poverty. Analyzing the study, Brian Fikkert and Steve Corbett of the Chalmers Center for Economic Development said, “Poor people typically talk in terms of shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, and voicelessness.” The study highlights that, by nature, poverty is innately social and psychological . . . In my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, my definition of “social action” takes into consideration that those living with the effects of poverty are subject to systems and structures, that is the powers, that make poverty more than just material. Social action, therefore, is principally the means by which one group offers alterative means to an end for another group, taking action or advocating for action to address social issues and community life. Within the context of poverty, social action is not merely charity, alms-giving, or the transfer of wealth. It is actions taken to address relationships between the poor and the non-poor and, as well, the relationship between the poor, the social structures that can cause or promote poverty, and individuals or groups whose actions create those social structures. Social action is, therefore, associated with actions taken by individuals or groups on behalf of others, in particular advocating on behalf of marginalized or powerless individuals or groups whose access to the systems of power are limited or nonexistent. We must understanding that being poor is more than the lack of something material, but is living with the effects of poverty upon the whole person. This will help temper our judgments about the poor and why they are poor—and perhaps move us as Christians to relocate ourselves into the lives of the poor. This way we will experience and recognize what it is to be “poor in spirit.” Then, we might very will gain insight and appreciate why Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3).

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed