Wasted top reads in 2018: Books that made significant impact on my thinking and ministry vision12/31/2018  I read a lot. Sometimes more than one book at a time. At the end of each year, I post the ten or so top books that have been influential to me, which I think other Christians and those in church ministry would benefit from reading as well. I don’t list journal articles, but I read a lot of these as well. But since you all will more likely buy a book than dig up an academic journal, I give you the most significant books I have read in 2018. I don’t have to agree with everything an author has written to be influenced—to rethink, to expand my thoughts on church, the faith, the gospel, mission, evangelism, discipleship, culture, justice, etc. These eleven books make the list because their subject matter will have lasting value on me. And, I believe would greatly help you on your discipleship journey as well. They are not in any particular order; more or less the order I read them throughout 2018. Nonetheless, I strongly suggest the two books by Richard Beck and Michael Goheen’s book on Newbigin’s “Missionary Ecclesiology” as very important and significant reads for those in church ministry. And, I highly recommend Stephen Backhouse's book on Kierkegaard is a fun (enjoyable) read that will help you think about your faith out of the box (out of the Christendom box the church finds itself in at this time). Enjoy. Church and Its Vocation: Lesslie Newbigin’s Missionary Ecclesiology by Michael W. Goheen Church Forsaken: Practicing Presence in Neglected Neighborhoods by Jonathan Brooks, Stranger God: Meeting Jesus in Disguise by Richard Beck Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective by Justo L. González Loving the Poor, Saving the Rich: Wealth, Poverty, and Early Christian Formation by Helen Rhee Delivered from the Elements of the World: Atonement, Justification, Mission by Peter J. Leithart Saved by Faith and Hospitality by Joshua W. Jipp Exegeting the City: What You Need to Know About Church Planting in the City Today by Sean Benesh Urban Hinterlands: Planting the Gospel in Uncool Places by Sean Benesh Kierkegaard: A Single Life by Stephen Backhouse Unclean: Meditations on Purity, Hospitality, and Mortality by Richard Beck

0 Comments

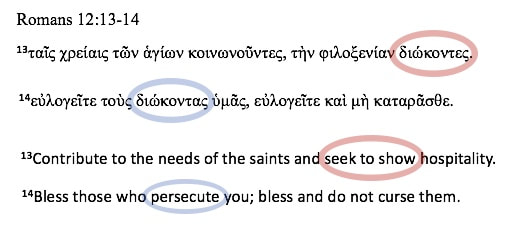

Working on Roman’s 12 for Sunday. There is a little creative punning by Paul in his Romans 12 (ESV). Most think of a pun as some form of joke or humorous quip; however a pun is a word-play, also called paronomasia. A pun can be both visual (the form of the word) and auditory (hearing), a form of word-play that suggests two or more meanings played off each other for rhetorical effect, harnessing the multiple meanings, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. Here in Romans 12, Paul uses such punning to emphasize the importance and significance of the gathered-church. “Contribute to the needs of the saints and seek to show hospitality” (v. 13). Here is my own translation, which reflects Paul's original word order and the reading of it out loud. Sometimes hearing it is the best way to catch the intent: “The needs of the saints, contribute; hospitality, intentionally pursue. Bless those who persecute, bless and do not curse” (Rom 12:13-14). Three things worth noting:

Wasted Passion Week Thoughts: “Show hospitality to one another”–– It's not what you think (really)3/5/2018 Some percolating thoughts on next week’s (3/11) sermon passage, 1 Peter 4:8-11, and in particular verse 9 in this context (see the last set of words and you will see why as you read my thoughts below):

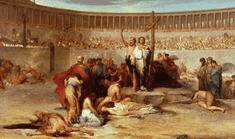

Can’t get around it: NT (expected) hospitality was risky business. First, it was (as it should be now) developed around unequals and strangers, aliens to one’s own patria (family), peers, and peeps; and if expected hospitality (e.g., 1 Peter 4:9) is for the purpose of opening one’s home for worship, instruction, and fellowship—that is to be the space for a gathered-church—that gathering would be, by its very nature and habitus, subversive and treasonous, for not only would it upset and upend the cultural norms that stabilized the social order of the empire, a cup would be raised to celebrate and acknowledge that the dead-but-now-risen-traitor-criminal Jesus, not Caesar, was Lord and King—and coming again! Our modern expression of church does not fall under this type of hospitality (space), which needs to be—per the NT, really, ought to be—a part of our ecclesiology. The empire (i.e., our culture, social associations, and government) does not consider us too much of a threat in how we meet or who meets with us. What I find interesting is that when a church does start to act or envision church in this hospitality-way, it is a threat to the existing church. What’s up with that?

Here are eight books On My Table for early 2018; the first four listed, I have already begun reading:

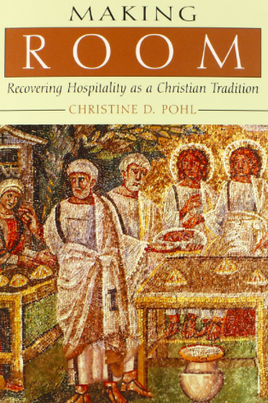

I read books that challenge me, push my convictions, and expose my idolatries. No book, recently, has done this as has Christine Pohl’s Making Room: Recovering Hospitality as a Christian Tradition as I digested page after page. As many who have the patience to read my posts and blogs, I have been rethinking church and its relationship to the poor for some time now. It’s has gotten somewhat more personal as I have been challenged to reevaluate the concept of Christian “hospitality.” Pohl reminds me that biblical hospitality isn’t entertaining friends and family, but the household extending relationships and meeting the needs of the poor and marginal, nearby and traveling through. Typically, most in the church seem to understand hospitality (or the “gift” of hospitality) to be the entertaining or hosting of those we already have some form of relationship (“established bonds”) or shared social status and “significance common ground.” Here, “[h]ospitality builds and reinforces relationships among family, friends, and acquaintances” (13). This kind of hospitality reinforces the shared social status among host and guests, wherein the guests give or affirm something by their presence to the host. Frankly put, this “kind” of hospitality is simply entertaining of guests who affirm or build the host’s social or ecclesiastical status. This is not biblical hospitality. There is commonality, that is the liminal space is shared by hosts and guests before, during, and after the act of hospitality. However, biblical hospitality is more closely related to offering space, comfort, and resources to the stranger, the poor, the marginalized—someone outside or estranged from one’s social status, whereby nothing is gained or affirmed by the hosts. This kind of hospitality, framed by the nature of the gospel itself, is for those disconnected from basic relationships and resources. As Pohl reminds, this “hospitality is central to the meaning of the gospel” (8). Thus, in a real sense,“[h]ospitality is the lens through which we can read and understand much of the gospel, and a practice by which we can welcome Jesus himself” (8). The act of hospitality is a concrete display of the gospel. Prior to hospitality, the host and guests might very well be living out a world that affirms verticality; yet the household becomes a gospel-liminal space that affirms horizontality. This reality—where the gospel is displayed, that is where a leveling of human relationships takes place amid the basic human entity, the household—is an expression of God’s kingdom. Granted biblical hospitality isn’t a mere “how to” for the Christian faith nor should be considered lightly. Yet, I cannot rethink church without considering the Christian tradition of biblical hospitality. It is stretching, convicting, and stressing me to think more deeply. Here is a series of quotes from Making Room that confront me on the issue of being Christian, having resources amid the scarcity of many, and the concept and practice of hospitality. “These hospitality communities embody a decidedly different set of values; their view of possessions and attitudes toward position and work differ from those of the larger culture. They explicitly distance themselves from contemporary emphases on efficiency, measurable results, and bureaucratic organization. Their lives together are intentionally less individualistic, materialistic, and task-driven than most in our society. In allying themselves with needy strangers, they come face-to-face with the limits of a ‘problem-solving’ or a ‘success’ orientation. In situations of severe disability, terminal illness, or overwhelming need, the problem cannot necessarily be ‘solved.’ But practitioners understand the crucial ministry of presence: it may not fix a problem but it solves relationships which open up a new kind of healing and hope” (112). “Recognizing our status as aliens in the world is important for attitudes toward resources and property. Although for most of church history private property was taken for granted, its use among Christians was sometimes moderated by the teaching that everything beyond necessity belonged to the poor. Most of the normative discussions of hospitality assumed that God had loaned property and resources to hosts so they could pass them on to those in need” (114). “In the second-century writing of Hermas we can see an important connection between alien residence and the use of resources. The Similitudes began with the claim that servants of God are living in a ‘strange country,’ far from their true home of heaven. Given their alien status, it makes little sense for believers to collect possessions, fields, or dwellings. Christians live under another law; whatever they have beyond what is sufficient for their needs is for widows, orphans, and other afflicted persons. God gives more than sufficiency for that purpose, not for making believers comfortable and vulnerable to the enticements of a strange land (Sim. 1:1–11)” (115). “If Christians live ‘in a strange land as though in [their] home country,’ they build ‘extraveagent mansions,’ and indulge in ‘countless other luxuries,’ wasting their substance on ‘inanities’ [a nonsensical action, silliness]. Because, when forced to leave the land of their sojourn they will be unable to take their possessions and buildings with them, Christians should instead use their wealth to benefit those in need” (115). Seems that much of our "church" experience affirms our cultural's values regarding social status, continues the horizontal nature of social status quo, and displays the divisions fostered already in society. The way we do church isn't neutral to the issues of poverty, racism, and wealth. Biblical Christian hospitality reverses all of this and helps us to question what we truly believe as Christians concerning our "landed" status as aliens of a different kingdom.

Yes, I posted the set of most influential books I read in 2016. Yet, there are three books that have significantly moved me to rethink my gospelology (how come that’s not a word). Granted I’ve been heading this way, but in God’s gracious providence, he allowed or choose these three books to enter publication and find their way to me. The books underscored the things God has been teaching me this year. Two words can sum up what has been taught: horizontalization and leveling. The three books are:

These three books, more than anything, taught me about the two words--horizontalization and leveling--and their importance for a better, more proper understanding of the gospel and church.  I am sure I will post something soon on “horizontalization” and “leveling,” but for now, it is enough to say that God has taught me that the uniqueness of the gospel is leveling, that is, there is a leveling among believers unlike anything else upon earth. The table or the partaking of the Lord’s Supper is a leveling event (or should be). Our fellowship, i.e., our church life and worship, is a leveling of our social status’s. Whereas “leveling” is what should occur among believers and through its events of worship, the Table, baptism, and living in the world, “horizontalization” is the effects of the gospel that are displayed to the world; what outsiders, nonChristians, the unchurched, and the powers should see in and through our behavior, our habits, and our systems (i.e., the way we worship, the way we facilitate the Table, the way we do baptisms, and the way we live among people and together as a church). In other words, where such social leveling occurs, the church is displaying the horizontalization of the gospel. This is what I have been taught this year. Now, let’s see if I have learned anything. Check out my sermon on John 13, Jesus’s Community of Footwashers: His Public Presence in Caesar’s Arena of Death, that offers some of the insights on what I have been taught about "leveling" and "horizontalization." There is a link on that page for downloading the sermon and for listening to it as well (if you have the time).

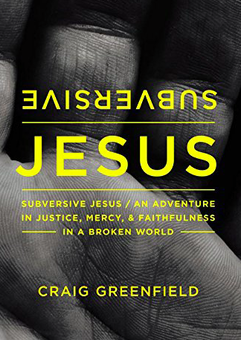

I am constantly looking for books I can give away or refer to that might move my friends, maybe just a little, to reconsider their understanding of the gospel and its relationship to the poor. Craig Greenfield’s Subversive Jesus: An Adventure in Justice, Mercy, and Faithfulness in a Broken World is, thankfully, one such book. This volume does exactly what I am looking for: it connects Christians to the issues of poverty and to the poor through reflections on the Bible and through the messiness of ministry. Greenfield points out that respectable Christians don't "throw in their lot with the poor” (22), yet he believes, as I do, that “there is a biblical mandate for Christ-followers to become lobbyists for the poor” (139). Subversive Jesus explains wasted evangelism very well, portraying the relationship between the gospel and social action through the ministry illustrations and, as well, through his autobiographical sketches of real life stories among the poor. Subversive Jesus isn’t just another book guilting Christians into helping the poor. It is as much a confession (of the struggles living out a subversive gospel) and story-telling as it is a reflection on the nature of the gospel and the person of Jesus as the New Testament portrays him. The content—yes, the rightfully convicting content—is embedded throughout the book within his family adventures in learning how to live among the poor—and as Christian neighbors. He confesses, “. . . it wasn’t long before we came face-to-face with the messiness of living on the edges of society with those who struggle—for we cannot separate the beauty and goodness of subversive hospitality from its challenges” (55). Greenfield shares their ministry of hospitality, that is opening up his home and dinner-table to the poor, homeless, and messy (and sometimes reckless) individuals who we, too, often turn away in our hearts long before we even have a table to invite them to. We are led into the vulnerability of the Greenfield family as they experience and learn learn some of the tougher aspects of home and hospitality ministry to the poor. He writes, “Those of us who practice subversive hospitality will forever live in the tension between our finiteness, our human limitations, and grace. It will break our hearts when we have to say no or close our doors” (57). Greenfield does not hold back on the exposition, that is, the power of portraying the Jesus of the gospels. He explains, “I began to understand what this upside-down kingdom on earth might look like. For Jesus’ life was bookended by an empire’s standard response to anyone who is a threat: violence and brutal repression” (24). In fact, he is right to call out church people, exposing how we have tamed Jesus to fit our more suburban (I prefer to say, exurban and nonpoor) lifestyles of home and church: “Many of our Sunday schools continue to encourage followers of Jesus to embrace a respectable Jesus, an agreeable teacher with pleasant stories to tell about how to be good. But no one would crucify this Jesus. No one would be threatened by such a bland personal morality. Instead, they’d invite this Jesus over for a cup of tea and a chat about the weather” (25). He reminds us of one of Luke's marks of the church strangely absent today: “God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them” [Acts 4:33–34, emphasis added by Greenfield] (52). The stories in the book are not prescriptive, he writes, but are demonstrations of how God worked in his life and, as well, his family’s life. He draws us into the overwhelming sense of hopelessness we can have when we are confronted by the effects of poverty and brokenness: “Who hasn’t felt like this in the face of our broken world? We can’t help feeling overwhelmed when we hear that on billion people live in slums worldwide, or that four hundred busloads of children die every day from preventable illnesses. It’s hard enough to face the challenges of our own impoverished neighborhoods and inner cities” (50). Yet, he is quick to point out that we have put too much reliance on non-church organizations and para-church ministries to deal with the poor and marginalized: “. . . we rely on soup kitchens and institutions. Instead of opening our churches and homes to the hungry, we are taught to “leave it to the professionals.” He says, “this is the way of the empire.” There is, however, hope for the poor in God’s kingdom and among Jesus’ followers. “Jesus promises that even though the empire is a cold and lonely place for the vulnerable, his kingdom on earth will be especially good news for the poor. As followers of Jesus, we need to figure out what that good news looks like as we respond to those who are suffering because of poverty and oppression, whether a beggar on the corner or an orphaned child in a slum halfway around the world” (68). Yet, we choose to live apart from the poor, separated from the people and the effects of poverty in which they, themselves, must—and mostly not by choice—live their everyday lives. “As people of privilege, we make choices every day about where we will live, where we will shop, how we will travel, and who we will spend time with. Often these choices isolate us from those on the margins of society. Our isolation from the poor shapes how we understand poverty, and it drives how we respond to it” (107) Many of us have the power (and platform) to change how we view and approach the poor and the issues of poverty—first in our own lives, then our church life, and, as well, through advocacy and example, in the world around us. But, Greenfield pin points the problem: “Those who hold the most power and authority in society are the least likely to want to change the system that produces poverty” (111). The Greenfield family understands the risk involved with following the subversive Jesus (the Jesus of the New Testament): “We realized at a very personal level that when we align ourselves with the poor and seek to be in solidarity with those Jesus called us to embrace, there will be a cost” (157). If the gospel is subversive to culture and power, what is it about your life as a Christian that is, well, subversive? I highly recommend Subversive Jesus for your own edification, perhaps as a small group reading among your church family. You will be convicted, encouraged, at times angered, and you will cry. But most of all, you will be confronted by the subversive Jesus of the gospels and pierced and humbled by a life (the Greenfield’s) caught up in the beauty, messiness, and ministry to the least among us. Greenfield is the founder and director of Alongsiders International (alongsiders.org), an organization that seeks to mobilize and equip thousands of young Christians in the developing world to walk alongside those who walk alone, especially the orphans and vulnerable children in their own communities. The Greenfields have lived and ministered for more than fifteen years in slums and inner cities in Asia and North America. Subversive Jesus is available on Amazon. And, his first book, The Urban Halo: a story of hope for orphans of the poor, is also available. Both books may also be found on Craig's website, craiggreenfield.com.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed