It is understandable that suburban, exurban, and affluent church congregations, typically, do not see the link between the gospel and the flourishing of their neighborhood. Here’s the problem: Which neighborhood? Whose neighborhood? And, O by the way, our neighborhoods by definition are flourishing. Suburban and exurban congregations tend to be a mix of like-minded, demographically related, geographically similar people who travel various distances away from their own neighborhoods to a building in an incongruent neighborhood (to most of the congregation), the place of gathered, weekly worship—the building they call “our church.” This is the habitus of Christians within suburban congregations each week. A habit that teaches, forms, and qualifies an understanding of the gospel. The neighborhood is a space we leave for church, more a concept of social structure rather than a concrete place or association; a place where my house is located, but detached from my church experience and faith. This offers a building-centered church experience that more easily relates to the command to love the Lord your God, but has no real, concrete relationship to love your neighbor(s) as yourself. In a real way, a suburban church congregation is without a neighborhood—at least without a specific one. There is no neighborhood for the church to ultimately be identified with, for the members are mostly transported from their actual neighbors and family in real neighborhoods to a one-size-fits-all neighborhood that is stuffed inside a building. Rather than a public faith that engages a neighborhood, practicing the second-which-is-like-unto-the-first-command to love one’s neighbor, more affluent and suburban/exurban congregations form a more privatized, truncated, thin faith (i.e., Christian experience) and, as a result, there is a bent toward more cognitive (knowledge-based) and behavioral outputs (i.e., activities) and outcomes. Thus, the church, the gospel, and discipleship are all aligned with a neighborhood-less social grouping, separated from the day to day realities of life in a neighborhood. Unexpectedly, the early church grew, not because they verbally witnessed, had an outreach program, or held bible studies; but, because they lived their daily lives in contrast to the world around them—their habits were different and their habits were noticed by their neighbors. And, not just in cultured, acceptable behavioral ways, but in concrete, intentional actions. Their discipleship included helping the poor, rescuing exposed (abandoned, thrown away) babies, adopting orphaned children, rescuing prostitutes (temple slavery), and meeting the needs of the widows (who were the most vulnerable and under-resourced population in the empire). This is how the body of Christ, the church, grew. The presence of Jesus was experienced in concrete intentional action through the church—practicing the presence of Christ amid neighbors. Typically for the non-urban churches, evangelism and mission is understood, not by kingdom righteousness, advocacy for injustice, and social action on behalf of a neighborhood, but by numbers of people funneled into a building for a worship service, a bible study, or special fellowship event—a head count of conversions or transfer growth. Church leadership institutes activities and behaviors to draw the unchurched out (and away) from their neighborhood (without actually going into those neighborhoods) and into the building (they call church), which is neighborhood-less (or at least in a neighborhood that is not their own). When the liminality of church life is separated from the daily life of a neighborhood, the gospel and its associated outputs (i.e., activities) and outcomes are disconnected from the life of their neighbors. When one’s own neighborhood consists of those who have had the privilege of flourishing and a church congregation is detached from a neighborhood, the Christian experience affirms a gospel unrelated to the flourishing of a neighborhood. Christian behaviors, then, are limited to relationships and social associations that affirm “traditional” cultural values (within that building) rather than including behaviors that understand the dynamic relationship between structures, systems, and people’s well-being within the context of a neighborhood. The gospel of the suburban church is a limited, one dimensional gospel. A one-dimensional gospel indicates solely a person/God dynamic relationship; whereas a multi-dimensional gospel includes the person/God dynamic and, also, creation/God, person/creation, and person/person. The habits of the suburban and exurban church makes it difficult to see the link between the gospel and the flourishing of a neighborhood.  For a more comprehensive study on the relationship between the gospel and social action, please take the time to read through my Wasted Evangelism, an exegetical commentary on Mark's Gospel. I am also working on another volume on Church Growth from an exegetical study in Ephesians, hopefully titled, Not (just) By the Numbers: Getting Beyond Building-Centered Church Growth in Search of Other Biblical Outcomes—a Thesis on Biblical Temple-Church Growth; see some posts related to these studies (evangelism and Not by the Numbers).

1 Comment

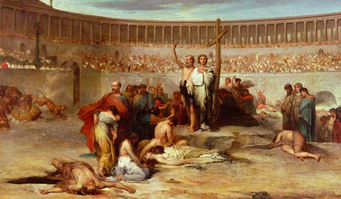

I must make two confessions up front as I began reading through the much treasured, but very often misunderstood John 13 footwashing scene of Jesus and his disciples: First, the eighteen plus years as a planner-grant writer, program developer, and instructor in the social action field, working for agencies that help the poor and low-come, has made me more aware of the Bible’s overwhelming connection to the poor. I most definitely read the Bible differently now. I can see more clearly what I have passed over, spiritualized, and, too often, ignored. I now pick up on nuances in biblical texts and stories that were blurred by my suburban, more privileged up-bringing and how my early Christian years were shaped. I confess am no longer a poor rich reader of the Bible. Second, and with a deep breath, I confess I am burdened and terrified by the call to minister in the Hill community in New Haven, Connecticut. I awake with burdens beyond what I could have imagined as I seek to minister in this broken, yet beautiful community called The Hill. Frankly (and some tell me, don’t let them know how you really feel, don’t show weakness), I am scared to death, sometimes awakening and wondering, “What in the world have I gotten myself and my wife into here?” Scared I’ll mess it up. Frightened that my vulnerabilities will be seen. Afraid my shortcomings, my age, may exhaustion, my weaknesses, and inabilities will be too soon noticed. Yet as Paul heard from God, I too rest in the words, “‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me . . . For when I am weak, then I am strong.” So, with humility I approach the text, weak and a common sinner in the hands of an all-too-gracious heavenly Father . . . and you, with so many reasons to listen to others, but with hopes you will hear the text. Let us pray . . . Let’s time travel back to the first few hundred years of church history. Most of us are familiar with the Greco-Roman colosseums and the brutality of the gladiatorial entertainment in the days of the Roman empire. In those colosseums there was a theater of real, unashamed, and intentional death that was designed to displayed the vertical nature of society, of social order, who had status and who did not—and who was and wasn’t a person. Why do I start here? The arena of death and violence is, you must understand, still the experience of so many around the globe today and in most urban centers in the US and in The Hill community—designed by default and intention, in our very built environment—continues to affirm social vertical status and, dare I say, what we affirm as human. Yet, Jesus and the gospel itself point to a leveling . . . displayed in and through and by the church . . . John 13 will paint this picture for us. Religion in the Roman empire was widespread, huge, and multiple. And yet, no one would have imagined that by the early 4th century Christianity would become a major world religion with adherents numbering among the most significance slice of the empire’s population. But the church didn’t start out that way: the first small congregations had no power, no leverage of status, no influence, and certainly no money. So how? As we read through the early church literature and church fathers, one would look in vain for references specifically to “evangelism” as a verbal witness as a matter of the Christian and church life . . . in fact “speaking” would have probably done nothing and no one would have listened (anyway). Literally in the first few hundred years, Christian literature makes no reference to “evangelists” and or even “missionaries.” So, how? Back to the arena games, say around AD 203: The colosseum-amphitheater was a wonder of Roman engineering. Everything about the architecture and the events were to show off the vertical nature of life and social standing in the Empire . . . vertical . . . higher sections . . . seated by wealth and influence . . . how the stands were filled . . . the upper sections were the visual center . . . magistrates, landowners, benefactors, the elite . . . the entertainment of the populace to bolster status and prestige—all affirming the vertical values of society and civil life. All the while, who were in the death-pits, the forced entertainment of death at the bottom of the arena? Of course the gladiators and lions, but it was the bottom of society that faced death—criminals, the unwanted, slaves, the abandoned—all for sport and entertainment. There we also find small bands of Christians . . . but they faced death (face the beasts and gladiators) differently; their presence in the arena subtly subverted the carefully choreographed vertical event. The masses saw husbands (the paterfamilias, head of households), wives, slaves, doctors, former prostitutes, unwanted children standing together . . . expressing publically right there in the arena Christian horizontality. (Yes, that is a word.) When one would fall, the others would help them up to face death standing. They did not defend themselves in any way. Although the whole of the gospel and NT teaching is behind their behavior, but it is the fact that Jesus left a footwashing community and not a militia or even an academy to invade this world IS THE HOW Christianity grew to overtake an empire. Here in John 13 we have a portrait, along with Jesus’s words, a powerful image and reminder of what the Christian community is to look like in the private habits of our worship and out in the public, in Caesar’s arena of death. The cliché is an easy one: Jesus had to leave, but he left a community. The harder thing: John leaves a community of footwashers to show his love to a watching public world: Jesus’ presence in the world is displayed by a mutually loving church that demonstrates the leveling of humanity, the horizontality of God’s love. Our focus is John 13:33–35—and how these verses stand in the midst of the footwashing scene, surrounded by a traitor among them (Judas) and Peter’s brash, impatient display of allegiance. Little children, yet a little while I am with you. You will seek me, and just as I said to the Jews, so now I also say to you, ‘Where I am going you cannot come.’ A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another: just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another. By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:33–35). Everything seems driven by these words from our Lord, here in chapter 13 and all through John 13-17. So we will center on these verses through the footwashing and the outer bookends texts about Judas and Peter in John’s narrative. I. Setting the stage with the footwashing example–Jesus prepares his new community for his departure II. The juxtaposition: The Traitor (Judas) and Brash, Impatient Denier (Peter) III. The power and habits of our text: The Presence of Jesus is the loving-one-another church–the visible, tangible leveling power of the gospel For the full sermon text, please click the download file below . . .

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

||||||||||

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed