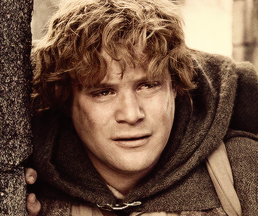

A Wasted Quote from Lord of the Rings: It's like the great stories, the ones that really mattered1/22/2018 Sometimes I am caught up in how hard and messy things are–not just globally seen through the lens and posts of social media, but in real lives and in the actual neighborhood where I am ministering. I remember the constant calls to go . . . go . . . go in my Bible College days. Youth. Youthfulness. Excitement. Passion. I remember. Every altar call. Every deeper-life conference. Every mission conference. Chapel after chapel. Go! Go! I am wondering why there isn't a line of young people, college aged, passion-filled Christians lining up to minister where I am ministering–one of the poorest, most under-resourced neighborhoods in New England? Where's the line? I love this neighborhood. I love the people in the Hill. But sometimes I feel so overwhelmed; it even got to me during service yesterday. Almost didn't get through the benediction after singing Kirk Franklin's "My World Needs You." Strangely, my mind as we closed drifted off to a scene in Tolkien's Lord of the Rings: Two Towers where Sam Gamgee says "It's all wrong . . . we shouldn't be here." I am overwhelmed at the task. But the love of Christ compels me to go . . . well, to stay and to bring the gospel where I now have been planted. God so loves the community here, the Hill, that he would build his church in its midst and call many to know Jesus and the forgiveness of sins. Sam's words are for those called to the humble but selfless mission to save others no matter the cost to themselves; to church planters planting churches in uncool and messy places on this globe and in places like the Hill.

0 Comments

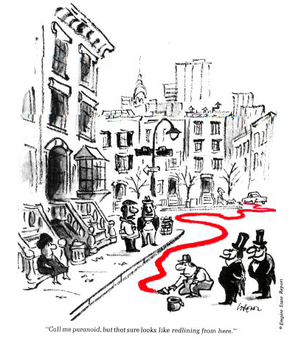

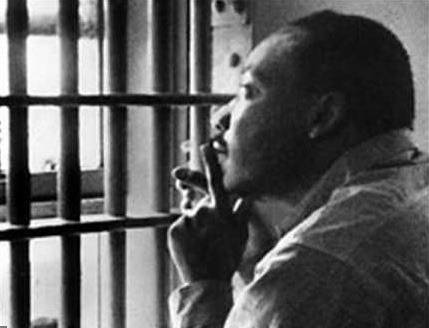

⬆︎ It is a wholly different thing to tell a person of means, of privilege, who has a measure of economic security and stability to "be patient, God is good" and telling someone who lives with food insecurity, unstable shelter, and a lack of economic opportunity to "be patient, God is good." Do you see how this works? ⬇︎ “Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was ‘well timed’ in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’ We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that ‘justice too long delayed is justice denied’” (MLK, Jr., Letter). “But in general, when ancient Latin writers used the term patientia, they didn’t have heroes in mind; they were thinking of subordinates and victims. Patience seemed an appropriate attitude for people of no account who were on the receiving end of actions or experiences. For these people—powerless, poverty stricken, and often female--patientia was ignominious. Patience was the response of people who didn’t have the freedom to define their own goals or make choices. Notably patience was a response of slaves, for whom it was an inevitability, not a virtue” (Alan Kreider, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire). Conclusion: Social Action as Christian Apologetic  Simply, affluent suburbanites, despite a claim to a higher work ethic or a more developed sense of responsibility, didn’t do it on their own; they had help along the way. (I know, many do not like to hear this, but no less truthful.) On the one hand, the non-poor’s social construction of reality, which they now experience as everyday life, allows them to benefit, not just from the market, but also from past actions of government that laid much of the groundwork for continued prosperity. On the other hand, the concentration of poverty in central-cities is not simply about laziness, slothfulness, or even personal sin. (I assume the non-poor who benefit from the current structure and mediating institutions are just as much “sinners” as those living in geographic areas of concentrated poverty.) Indeed, much of what is in place and experienced now as normal arose from various forms of racism and redlining practices, as well as “the concentration of subsidized housing projects” that, as Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck observed in their Suburban Nation, “destabilized and isolated the poor, while federal home-loan programs, targeting new construction exclusively, encouraged the deterioration and abandonment of urban housing.” The fact of poverty and the reality of those affected by it in the central-cities could not have happened any more effectively if it were actually planned and implemented with malice. Without the aid of government policies and subsidies, as well as municipally empowered zoning laws and discriminatory business policies, the foundation for exurban wealth in America might not have happened. Rather than lamenting this inequitable state of affairs, participants, including many non-poor Christians, have been encouraged to rejoice in the “prudence” of such strategies and the institutions, capitalism and the “mythical” market, that sustain them. The modern, non-poor suburban dweller is the heir of such socially constructed forces.

Emil Brunner once remarked, “For every civilization, for every period of history, it is true to say, ‘show me what kind of gods you have, and I will tell you what kind of humanity you possess.’” For the Christian and Christian community it is: Show me what kind of association you have with those living with the effects of poverty, and I will tell you what kind of god you worship. The reality of everyday life is that Suburban life and its enablers—the free market and human acts of power—are often at odds with the gospel, especially a gospel that has been formed by the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition. For the non-poor Christian, this is an idolatrous mode of living and does not offer a biblically defensible apologetic for the God revealed in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 *adapted from chapter 5 of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism

A duplicitous, self-righteous double standard in the “burbs Often, non-poor Christians respond to the poor as those who are living in a socially constructed reality that is mostly alienated from those living with the effects of poverty. The non-poor Christian’s participation in non-urban life causes a need for continuous reaffirmation for a biblical plausibility for their own social-location, one which alienates rather than connects them to the economically vulnerable. Without a sociological imagination, many non-poor Christians are not fully aware of their own socially constructed exurban reality, nor how it has been formed, which can lead to duplicitous, self-righteous double standards toward the poor. Often arguments rest, not on biblical grounds, but realities constructed by everyday life outside concentrated areas of poverty, namely the ability of the non-poor to have taken the “opportunities” presented in their socio-economic system to develop wealth and prosperity. The poor in the cities only need to do the same. Equal opportunity, not equal distribution of wealth is just, they reason. But this is not a fair picture, for the so-called “opportunity” has had a history and an opportunity that has been largely absent from social-locations with the most concentrated poverty, a consequence that is more akin to the injustice described by the prophets than simply the results of a good Christian work ethic and the invisible hand of the market. The exurban non-poor benefit from histories and institutions that have developed in favor of the suburbs and, for the most part, at the expense of central-cities—for decades. The shift from urban to suburban came with an intentional redistribution of efforts and transactions ranging from Federal subsidies to government policies to perceptions of urban and non-urban life. The ability to enjoy prosperity today, especially in upwardly mobile exurbia, is built on socio-economic transactions that have contributed to the current socially constructed reality of many non-poor (not just a good work ethic).

Furthermore, current upwardly mobile non-poor who live outside central-cities are the beneficiaries of a change in how home ownership was made possible. Even before WWII, Federal regulations began to restructure the home buying process to allow for lower down-payments and longer term-mortgages. The principle of amortizing loans made it possible to borrow on longer lengths of time for more affordable, smaller monthly payments. Later, after WWII, other Federal Housing Authority (FHA) policies helped to structure home ownership to be very attractive and easier to obtain, crafting regulatory guidelines for subdivisions on the outskirts of urban centers, the first fruits of what was to become suburbs. In effect, the government, through legislation and acts of congress (the FHA and Veterans Administration in particular), disproportionately encouraged new home ownership in the suburbs rather than fixing or rehabilitating older structures in urban centers. The sociological pressures resulting from the end of WWII, the “released pent-up demand for starting families and buying consumer goods,” a housing shortage in the central cities, the availability of low-cost mortgages for new homes, the mortgage-interest tax credit, mass production techniques in the housing industry all contributed to a rapid expansion of the suburbs. The shift in regulatory policies for long-term-little-down mortgages, government subsidized development of major highways for access in and out of central-cities, the GI Bill (a government funded education/training program), and other Federal aid to the newer exurban regions made prosperity possible as we know it today. Zoning laws and affluent developers, not just the invisible hand of the market, protected the preferences of those with power. Furthermore, advertisers of home-related products, women’s magazines, the FHA, and bank officials all sought to make, as Robert A. Beauregard explains in When America Became Suburban, “the sharpest possible contrast between the private, comfortable, safe, and protected environment of the suburbs and the open, competitive, dangerous, and seductive world of the central city.” The invisible hand had and continues to get help—sometimes through Federal, State, and municipal efforts; sometimes through creative marketing; sometimes through celebrity-trend makers; sometimes by politically empowered zoning codes. Growth and decline, expansion and contraction, growth in one area at the expense of another area—all unavoidable within a socio-economic system that prizes “progress,” supported by desire for upward-mobility (and, too often, greed), promote the ultimate goal of “the Suburban Way of Life.” It is an empirical fact, the system and its mediating institutions ignored its central-cities and promoted life in the “burbs” as the ultimate goal of prosperity, all for the gods of growth, progress, and the new. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 *adapted from chapter 5 of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism

I am reading or have read recently a number of books that seek to explain how we arrived at our very distinct demographic and mostly ethnic divisions that exist today—urban, suburban, and now exurban. (I will leave the rural landscape for others who have studied it more adequately.) Amid these books I am also learning how we have developed a functionally dependent class, mostly non-white, that live and try to survive in the most dense urban areas of our country. Much of what I have read affirms my own writing on the subject, which found its way into chapter 5—“Idolatry and Poverty: Social Action as Christian Apologetics”—of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church’s Task of Evangelism. Below is a three-part adaption of the latter subsections of this chapter. Idolatry promotes a defective social reality for the non-poor Christian In his Nature and Destiny of Man, Reinhold Niebuhr observed that idolatry is making the contingent absolute, something relative into “the unconditional principle of meaning.” Luke Timothy Johnson points out that, when we consider something as ultimate, this is worship, not just what our lips or cultus ritual render, but in the exercise of our freedom in service to that which we consider absolute and unconditional, and, thus, derive our significance. It is, however, not just an image fashioned with gold and silver that provides the danger and potential of idolatry, for the Bible is clear, such man-fashion idols are no-things (Isa 41:21–24; 44:10; Ps 115; 135; Acts 14:15; 1 Cor 8:4; 10:19; Gal 4:8). Johnson reminds us that “important idolatries have always centered on those forces which have enough specious power to be truly counterfeit, and therefore truly be dangerous: sexuality (fertility), riches, and power (or glory).” It is the body of knowledge that accompanies the object and the habits of service in worshipping the objects (i.e., idols) and, then, the social and cultural habits that follow that develop an everyday “world,” with meaning and definitions for relationships (repeated action, mundane habits), that objectifies reality and maintains significance and plausibility (its symbols and corresponding institutions). Our socially constructed world, then, is reality formed by our service of worship and sustained (validated) through the habits and experience of everyday life.

However, to understand fully the non-poor’s everyday reality, it is simply “not enough to understand the particular symbols or interaction patterns of individual situations.” It is how the “overall structure or meaning” within “these particular patterns and symbols” are experienced. As we seek to apply the gospel that is embedded with texts regarding idolatry (e.g., the overwhelming number in Mark’s own gospel) and, as well, texts indicative of relationships toward the economically vulnerable, it is important to understand how the social-location experienced by many non-poor Christians was formed and its implications for their (i.e., the non-poor) participation in the outcomes of this social-location. Religion once offered an integrating principle that helped provide a “life-world” that was “more or less unified.” But, modern life not only provides a less unified everyday life, now religion often aligns itself with the socio-economic forces that help sustain the plausibility of our faith, which can then inoculate the non-poor Christian from the idolatrous forces embedded in their social-location. Over time new symbols and signs (lawns, yards, gated communities, commutes and highways, social status, shopping malls, upward mobility, the market, double-entry accounting, etc.) that permeate the social-location the modern non-poor Christian experiences as everyday life compete with biblical symbols (e.g., the words of God, the cross, redemptive-historical acts of God in history, etc.). Johnson reminds us, “Prior to any action or pattern of actions we might term ‘Christian’ is a whole set of perceptions and attitudes, which themselves emerge from a coherent system of symbols, and an orientation toward the world and other humans, which we call Faith.” In fact, the very habit of experiencing the fragmented, often unintegrated social-locations over and over everyday might feel like freedom bestowed by our socio-economic system, but actually weakens the plausibility of biblical faith to inform our home world. Non-poor Christians are in danger of idolatry when finding themselves in need of affirming “this worldly” system and its institutions as God-given in order to be at home, plotting their lives on the societal map provided by social institutions rather than biblical discipleship in order to relate—comfortably, plausibly, securely—to the overall web of acceptable meanings in society. As Berger in Homeless Mind points out, because of the plurality of social worlds—work, school, play, third places, highways, commutes, home, shopping, church—in modern society “the structures of each particular world are experienced as relatively unstable and unreliable.” The separated sectors of our social world are rationalized and relativized, forcing the non-poor Christian to justify religiously this worldly system and institutions in order to feel less exposed and vulnerable and more relevant and secure. After decades of political alignment and religious justification, for the most part, the non-poor Christians living in the suburbs now feel at home.

Here are eight books On My Table for early 2018; the first four listed, I have already begun reading:

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed