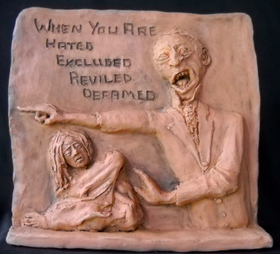

Wasted Rough Cut: Listening to Jesus' Beatitudes (in Luke) and not robbing the poor of their power.1/16/2022 *The following is a set of sermon prep-notes and ideas for my sermon on Jesus' Beatitudes as Luke presents them in his Gospel.  I am amazed, and saddened as well, the lengths Christians, even commentators, will go to read out the “poor” in a vast majority of Bible texts that are so clear and should be necessarily inferred as actual poor. This robs this text in Luke 6 of its gospel-transforming-power, especially with regard to Jesus’ words in the Beatitudes. In Luke 6:20b we read, “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” (Below I offer my own translation of this verse.) One would think a learned degree is not necessary to hear Luke sets Jesus’ reference to the “poor” in contrast to his equally disturbing reference to the “rich” in what is obviously a paralleled statement in Luke 6:24: “But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.” In fact, it is much harder to spiritualize Jesus’ reference to the “rich” than it is his reference to the “poor.” This can be seen by the fact hardly anyone does. Luke’s Gospel is filled with such contrasting of the poor and the rich in Jesus’ teachings and in forthcoming parables that we cannot escape something about actual “rich” and actual “poor” is afoot. For example, in Luke 16:20, Jesus compares the poor beggar with the rich man who disregards the beggar only to discover the poor beggar is the one who is blessed in heaven while he was filled (satisfied) on earth: “but now he [the poor beggar] is comforted here [after death], and you [the rich man] are in anguish [after death]” (16:25b). Certainly, given the wider narrative context, there is a link (i.e., a clear and necessary inference) between the “Blessed are . .” and the “But woe to you . . .” contrasted sets in the Luke 6 Beatitudes. This poor/rich contrast is also seen in Luke 21:2, when Luke/Jesus refers to a “poor widow” in contrast to the rich and the pompous pharisees. Later, in Luke 7:22, the proof that Jesus is the messiah and that the kingdom of God had arrived is given by observing what was happening in Jesus’ ministry: “And he answered them, ‘Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, the poor have good news preached to them.’” Again, in Jesus’ parable of the great feast in Luke 14, the rich are instructed to not invited those who can repay, but invite the poor who cannot repay–again, here is that link to the Luke 6 Beatitudes. (There is also a narrative link to the forthcoming poor beggar/rich man scene in Luke 16 as well.) “But when you give a feast, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the just” (Luke 14:13). Even when the context and the clear narrative meaning of the text is referencing the actual poor there is a tendency to read out the poor and read in anyone who is “poor of heart.” That certainly keeps the rich satisfied and the poor, well, still poor. This disallows the obvious social/institutional system-contrast Luke has already set up for us in his introduction, that is Mary’s song: he has brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty (Luke 1:52-53). Thus, restoring the gospel-transforming-power we have robbed from the Beatitudes by reading out the poor from this text.  Luke 6:20b: Μακάριοι οἱ πτωχοί, ὅτι ὑμετέρα ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ. ESV: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” My wooden translation: “Flourishing*, the poor (the marginal and powerless), because allotted to you** is the kingdom of God.” Smoothed out: “Flourishing is the marginal and powerless, because to you—the marginal and powerless—is allotted the Kingdom of God.” I try to pay attention to how early church writers render texts of Scripture. Tertullian (155 AD–220 AD) gave Luke 6:20 and this Beatitude the latin beati mendici—“Blessed are the needy,” or “Blessed are the beggars.” He is not the only one who translated the word πτωχοί as “beggar.” While it (i.e., “πτωχοί,” poor) can and probably does simply mean the “poor” (its detonated meaning), its connotative meaning gives a more powerful nuance. For example: The word we translate “poor,” πτωχοί is vivid: one who crouches (as in shamed to be seen) and cringes (as in cowering in the presence of others), thus it is often used of “beggars.” No doubt it carries the concrete reference to someone who is needy, someone who has no power, someone we typically call “marginal” and powerless in society, and in the ancient world one who would have been called “not-or sub-human.” The two times Luke uses this word associated with a particular person are the beggar named Lazarus (being contrasted with the rich man who had everything and disregarded Lazarus, 16:20) and the poor widow vs. the rich/the duplicitous scribes (21:2)—can’t you see what Luke is doing between the Beatitude promise/affirmations and the wider story in his Gospel narrative? There are more of these throughout the Gospel (see chapter 14 for example). The word we typically render the “poor” (πτωχοί) is better understood by how it is used. While it is certainly can be used metaphorically to mean humble,*** or as a Christian virtue, or still better, more simply, as not-arrogant, there is a reason why this word can be used this way. The word has a concrete meaning range of someone without economic means, who is marginal and powerless–again, this is why the word “beggar” isn’t a stretch and certainly fits Luke’s other uses of the word throughout his Gospel. And, it also fits the extremes of the power/powerlessness contrasts that Luke uses to describe the arrival of Messiah and the teachings/parables Jesus uses throughout Luke’s Gospel: beggar (the least and the most without power) vs. the rich (or the mighty, those who have the resources but do not share with the poor, and/or those who do only to/for those who can pay back). You can see how Luke has shaped his Gospel and why it seems a necessary inference to take “the poor” in the Beatitude as exactly that, the poor as in the marginal and powerless. *”Flourishing” is a far better translation for Μακάριοι than either “blessed” or “happy.” **The “you” is a bigger word than the simple pronoun σύ (you), but as you can see is the word ὑμετέρα, which carries the idea of “allotted to you” or “possessed by you.” Split hairs which nuance, but since this is God’s action or promise I lean toward the nuance of “allotted.” ***In the Greek world, the nuanced meaning of “humble” or as a Christian virtue is a much later connotative meaning given this word, πτωχοί, and should not be read back in to how Luke is using the “poor” / “rich” contrast and comparison.  “Blessed are you when people hate you and when they exclude you and revile you and spurn your name as evil, on account of the Son of Man!” (Luke 6:22). While I agree these words are directed at disciples, who will become Jesus’ representatives (probably the meaning behind “on account of the Son of Man,” v. 22e), the description here plays double-duty. Obviously (because we have the whole of the NT to give us fuller understanding) just because one is “poor” or “hungry” or weeping (probably all three is one group), this does not mean they do not need to be born again or qualifies them as automatically born again (something that needs to happen in order for sins to be forgiven, be justified before God, and gain eternal life). Nonetheless, it should be pointed out that “crowd” who came for healing and exorcism would not have been the ones honored nor socially accepted in either the Greco-Roman world nor the Jewish world for that matter. They'd have been the truly marginalized, rejected, and considered sub-human. “. . . a great multitude of people from all Judea and Jerusalem and the seacoast of Tyre and Sidon, who came to hear him and to be healed of their diseases. And those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured” (Luke 6:17c–18). They would have too easily identified with being hated, being excluded (separated, marginalized, rejected, avoided, ostracize), being reviled, and shunned. The dirty, shameful words trigger: diseased and possessed of unclean spirits. This was their lot, their place in the social castes and institutional systems of the world. The “apostles” that were just chosen (6:13-16), along with the “great crowd of his disciples” (v. 17b), whom the sermon is directed (v. 20), while the larger crowd was listening in—the teaching was very public (and outdoors I might point out!)—they would be as marginalized as the ones who came for healing and who troubled with unclean spirits. Jesus’ appointed representatives (the apostles) and followers (the wider crowd of disciples) would be the poor, the hungry, and those weeping—everything would be turned on its head and the world, its social structure and institutions would hate, marginalize, revile, and spurn those who were truly the blessed, that is the apostles and disciples of Jesus who followed Him and proclaimed this teaching—all on account of being the representatives of the Son of Man, those whom Jesus was reproducing Himself in the world. Yet it would be to them the kingdom belongs, their stomachs would be full (satisfied), and fulled with joy. The appearance of Messiah Jesus and the proclamation of the Gospel—as Jesus’ inaugural sermon indicated (Luke 4:18-19; cf. Isaiah 61:1-2 and 58:6-7)—changes everything about how the systems and structures of this world work (cf. Luke 1:51-53). This is what the beatitudes indicate and mean–and how they should be applied. However, we have traded this all away by making the church (and by that I mean churches and their institutionalized systems) reproduce the world in everything from measures of success to leadership and training to evangelism and (sadly) in our ways of doing and measuring being missional. Discipleship, too often, mimics how the world works rather than what the Beatitudes display.  Lastly, discipleship is not one size fits all. The way Luke has presented Jesus’ Beatitudes is more to expose the structural and systemic, institutionalized empire (Rome-centered, adamic natured) way of defining who is and who is not blessed, who is and who is not honored, who is and who is not fully (or at all) human. What divides humanity. And, addresses the danger of using the world’s way of addressing the issues of poverty and affluence. Take the poor out of Jesus’ reference to the poor and this is lost. This–that is, the Beatitudes are not about “salvation” (that is getting into the Kingdom of God), but about what the new community of God looks like, how it’s system, if you will, works. And this means applying discipleship somewhat (not entirely, but in some specifics) differently to rich disciples and poor disciples. The way to blessing (i.e., kingdom flourishing) is not the way of the world–it is a wholly other way (or as the title of a book I am reading puts it, not the way of the dragon, but the way of the Lamb). Christianity, that is our faith in Christ and our relationship to the church, is not a pathway to success (that is being one of the “rich”). And, our present power granted to us by our place or status in the social structure and current institutions no longer defines us and our neighbors. If one is among the “rich” one best rethink their relationship to the poor and adjust appropriately. Other Sermon on the Plain Wasted Blog thoughts

0 Comments

From the Greek geek (be patient, it's a rough cut): While most translations of Romans 12:9-13 are just fine, some nuances are lost (as those who speak other than English sometimes say) in translation. Here’s one . . . from verse 9 that’s worth noting. “Let love be genuine. Abhor what is evil; hold fast to what is good” (Romans 12:9, ESV).

There are no verbs. We (even they) had to provide them, but should not be at the expense of hearing how Paul set out his written words. And, in this case (v. 9), the two following participles should be heard as “how” (thus, my “by”) “the love” is “sincere,” that is, the manner in which “love” is shown to be sincere is in abhorring evil, holding fast the good. This gives Christian (or should I should, given the context, church) love content--action. And, also noting that Paul’s consistent use afterward of a specific, repeated grammatical construction (i.e., for other Greek geeks, a string of dative phrases—again with no verbs) probably indicates what “good sincere love acts like”: This is what church good love looks like: “Love one another with brotherly affection. Outdo one another in showing honor. Do not be slothful in zeal, be fervent in spirit, serve the Lord. Rejoice in hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer. Contribute to the needs of the saints” (ESV). Note: Of course, English versions need to iron or smooth out Greek-to-English renderings to make it more readable . . . most of our English translations, if watching all such linguistic and grammatical nuances of a language (i.e., the koine Greek of the NT) that was written to be heard and not read (so much) would be quite choppy and tiresome to just read . . . but sometimes it’s good to get at the Greek that was to be heard (and not just read).

Sometimes chapter divisions can detour from hearing what the author of a biblical text has said. This is so true of 1 Corinthians 13. Most, at least from all the sermons I have heard and the weddings I have attended attest. Nonetheless, chapter 12 and chapter 13 of 1 Corinthians are in need of being heard together as if there is no chapter division between them. In fact, there is a bookend link between 12:13 and 13:13: ζηλοῦτε δὲ τὰ χαρίσματα τὰ μείζονα (12:31a) μείζων δὲ τούτων ἡ ἀγάπη (13:13b) Even those who don’t know New Testament Greek can see it––you can see the word “greater” (μείζονα, 12:31a / μείζων, 13:13b) at the close of chapter 12 and the close of chapter 13. Different endings (like Spanish), of course, but the same word: μέγας (great/greater) in 12:31a and 13:13b. The NASB, as do other translations, offers what I think is a much better read than the ESV: “But earnestly desire the greater gifts” (12:31a, NASB) Don’t know why the ESV translates the word μέγας as “higher.” I suppose it could, but this doesn’t help the English reader. The mistranslation masks the bookends here, which, in turn, masks the dynamic relationship between 1 Corinthians 12 and 13–these two chapters need to be read as one. So you can see (and hear) what Paul has crafted (with my more word for word translation):

So what does this do for us as we read chapters 12 and 13 together? First, we take and read the two as one thread and not separate chapter 13 as if it is a stand-alone-text about the vague notion of “love.” Witnessed by the mistaken use of the “Love Chapter” during weddings. Chapter 12 is most certainly about church, so for Paul, chapter 13 is about church as well. Second, we just had a chapter (12) on the one body of Christ—and please understand Paul is specifically referring to local churches, meeting in someone’s home, thus, “To the church of God that is in Corinth,” 1:2a): one body, many members (cf. 12:12, 27). Paul begins with the spiritual gifts (12:1), to which he will return in chapter 14, but makes a turn toward people-related gifting at the end of our chapter 12: apostles, prophets, teachers, those that do miraculous gifts of healing, helping, administering, and of course tongues.

Yep. Everyone wants these powerful, status-granting, attention-centered spiritual gifts (let’s be honest). Thus, the need for chapter 13. So, Paul asks,

Yet, he says there is a better way, a more excellent way. Paul then concludes our chapter 12:

Then, Paul instructs his readers/listeners on this more excellent way:

Let’s read 12:27–13:3 as one thread, of course with my interpretative spin (but I think it’s there in Paul’s meaning, a fair reading):

Well, this is a radical thing we have going on here. A new community built on the Love, not status, education, bloodlines, abilities, usefulness, or even spiritual office or gifting. And, then the reader/listener has Paul’s final charge: “So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love” (13:13).

We’ve come to an “end time” text in Matthew, chapter 24. Too many Christians, preachers, and modern, self-appointed “prophets” mine this chapter in search for how they may “discern” the signs so they can announce “the end is near” (usually accompanied by some action that is needed, everything from send money, give more money, stop letting, go vote . . .) Even though we have 2000+ years of everyone getting it wrong, plenty still predict and announce. When I was pastoring in Pennsylvania in 1987, I received a free book in the mail, 88 Reasons Why Jesus is Coming Back in ’88. Well, Jesus didn’t. So the next year, I received a new book from the same author entitled, 89 Reasons Why We Were Wrong in '88 and Why Jesus is Coming Back in ’89. You can’t make this stuff up. Well, here we are, it’s 2019. And, we still have sign pointer-outers and prophetic manipulators and, even, innocent, well meaning Christians seeking signs and pointing out why “we’re living in the end times.” If you skim through Matthew 24 and Matthew 25 (which should be like one chapter together) you will encounter the twin themes of “it’s not the end” and “you don’t know when the end is coming so be ready.” So, perhaps we should take this to heart and listen better to Jesus. Being ready isn’t about discerning the times and looking for signs, but enduring to the end. “You see these sign, endure to the end (since you don't know when it’s the end end).” What’s truly interesting, the parables that follow the “signs” section of Matthew 24 all push the reader toward being ready because you don’t know when it’s the end end. There are some important parallels we gloss over, or ignore, or don’t take into account, namely each of the parables–the faithful servant (24:45-51), the ten virgins (25:1-13), and the “faithful/unfaithful investors” (25:14-30) and the “sheep and the goats” (25:31-46)–all end in pretty harsh judgement . . . Matthew intends some parallelism here . . . they are all teaching basically the same thing. So, this is important to grasp. While waiting and being ready and seeking to endure, the Christian community is to be characterized by . . . go ahead, read Matthew 25:31-46 . . . you got it . . . by feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, by welcoming the stranger (don’t think US Border, that, too, is a misdirection; think your home, your church, your neighborhood, your circle of friends and acquaintances), by clothing the naked, and by visiting the sick and imprisoned. Matthew connects the “end times” teaching and the “sheep and the goats” judgment, so we should as well. Church is expected (a church in a place, in a neighborhood is expected) to live (together) in such a way as to create space (i.e., habits, lifestyles, life) to make it possible for the hungry to be fed and the stranger welcomed and the sick and imprisoned visited for the “end” is nigh in that Christ Jesus comes to us in the poor, the hungry and thirsty, the naked, the sick, and the imprisoned. So, Christian, stop seeking signs. Endure ’till He comes by doing what Jesus has been doing (in Matthew since chapter 4, i.e., ministering to the poor, the outcast, the unclean, the marginalized, et al.). Stop pointing out signs (“Oh, it must be the end, see how bad it’s getting!” or “Look what’s happening with that country . . . or those politicians . . . or those people!”). Just stop it. And, stop listening to it. It’s distracting you from true endurance, which means actively helping, serving, caring for the poor, the outcast, the marginal, the unclean.  Furthermore, there is an interesting twist afoot when we consider the thread of “second coming sign” texts in Matthew 24 and the juxtaposition of the three Matthew 24-25 parables and the parable of the sheep and the goats: The three parables, along with the noted (above) harsh conclusions, are also stories about a Master delayed (χρονίζω, chronizō) and who comes (24:48-50), a bridegroom delayed (χρονίζω, chronizō) and who comes (25:5, 10), and a Master who goes on a journey, “yet after a long time” (μετὰ δὲ πολὺν χρόνον, meta de polun chronon)* comes (25:19). Then in the sheep and the goals parable (25:31-46), we have the Son of Man (i.e., Jesus) who comes (25:31). Here, we have a slight nuance to the concept of “coming,” namely the “coming” judgment is based on the incidences of Jesus coming in the persons who are poor, neglected, under-resourced, unclean (i.e., hungry, thirsty, naked, homeless, sick, and imprisoned). Of course there is a final “coming” when Jesus, as the Son of Man judges and separates the sheep and the goats. Yet, this coming-judgment is based on what the people (i.e., Christians, at least outwardly) do and do not do to/for/with the Jesus who had come as someone hungry, thirty, naked, homeless, sick, or imprisoned: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it [or not did it] to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it [or not did it] to me” (cf. 25:40, 45). It seems clear, from the parallels in the parables and the juxtaposition of the coming-judgment of the sheep and the goats, that is, being ready, staying alert, staying woke while Jesus “delays” and being prepared for the final coming is repeating the same ministry that Jesus had illustrated (i.e., the fishing) in Matthew 4-23, that is healing and touching and feeding and caring for the poor, sick, and unclean. The true signs of His coming is the church among the poor, outcasts, marginalized, and unclean. Don’t be a goat (nope). Be a sheep. Be ready. Be prepared. Be truly woke . . . when Jesus comes to you as one of the least of these (or go to them, be among them), so that you may be ready when he comes as the Son of Man on that Day.

Some preparation for this coming Sunday’s teaching/sermon and some exegetical fun with Ephesians 4:11 (for those that like this sort of thing)

Elsewhere in the New Testament (and in Greek literature in general), when a writer strings words together, that is creates a run-on list of related words (cf. Ro 12:2; Phil 4:6), the sense is to describe the same thing, that is one thing. So what we have, here with Paul in Eph 4:11, probably should be taken in the manner of other similar Greek stringing to emphasize “teachers” of the church—“the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds” (noting and leaving in the repeated use of the definite article, “the” (τοὺς) that is left out of many English translations). The καὶ (and) that precedes the word διδασκάλους (teachers) should, most likely, be read epexegetically, that is with the meaning “namely” or “that is” (in this case because of the string of words, “namely that are”). The “teachers,” then, explain the nature and give summary (the point) of the previous string of words, “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds.” Most older English translations mask the obvious string by inserting the word “some” before each office. The NIV and ESV give the sense of the original (Greek) by showing the definite article that is used (τοὺς, the) before each in the string. The exception is with διδασκάλους (teachers); there is no preceding definite article. Some (I used to) just take the lack of an article to be linked solely to “the shepherds” (τοὺς δὲ ποιμένας καὶ διδασκάλους)–i.e., shepherds that teach; yet there is good sense to see the whole string (which is very reasonable and most likely) to be in the frame of the epexegetical phrase καὶ διδασκάλους (namely, that are teachers). Thus, my reading: “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds, namely [καὶ], that are teachers.” This makes grammatical and syntactical sense of the string and the repeated definite articles, and the lack of article with “teachers.” (See below* regarding my comment on the μὲν . . . δὲ construction, on the one hand . . . and on the other). We should read Ephesians 4:11: “God gave, on the one hand (μὲν)* apostles [who set the foundation of apostolic teaching and traditions (cf. Acts 2:42)], yet (δὲ) on the other hand, [He gave] teachers that speak-forth the Word (i.e., prophets), that proclaim and spread the good news (i.e., evangelists), and that guard, protect, feed (instruct/disciple), and care for the flock (i.e., shepherds).” I believe, given the wording and syntax of this verse, what I propose here is a fair and faithful reading of Paul’s intention for writing this to the church in Ephesus. The “apostles” are foundational in that they, historically, passed on (i.e., Peter, John, James, et al.) or delivered (e.g., Paul, Barnabas, et al.) the apostolic traditions (i.e., the teachings of Jesus and their intentions) at the first as churches where planted and spread throughout the known world. On the other hand, “the prophets and the evangelists and the shepherds” are the “teachers” that continue to pass-on apostolic tradition/teaching to the gathered-believers (or local churches) as the word spread and took root geo-demographically. I take the first office (“apostles”) as temporary once for all time and the second set of offices (and if you don't like the word office, “roles,” then, works just fine) as teachers for the gathered-churches to cause unity, maturity, and growth throughout time until . . . the word Paul uses (4:13) . . . until the fulness of Christ is accomplished in time and space on planet earth (cf. 1:10; 22-23; 3:19; 4:13c). In the rest of the paragraph (Ephesians 4:12-16), we will learn that these people—note: I take these more so as offices (or, again if you prefer, roles) filled by people (who are able and/or appointed to pass on apostolic teaching) because, rather than using a relative pronoun, i.e., those who prophecy/forth-tell, who evangelize, and who shepherd, Paul is intentional in using the definite article (τοὺς, the) before each word—they are given (i.e., gifts) to God’s people to move them toward the unity of the faith and the knowledge of God’s Son, toward perfection (i.e., maturity), and toward the fulness of Christ (that is being church, which is His body in locales, scattered throughout the earth, i.e., churches). At CPC in The Hill, we have, for a number of weeks, heard in the Gospel of Matthew about Shepherds and God expecting that teachers were to carry on the work of the ministry in the church. We noted that sheep die without shepherds (cf. Matt 9:35-38). We have heard about bad/poor/false leaven (i.e., teaching) and that we must take serious the instruction of a cross-centered teaching (Matthew 16 for example). So, our little detour in Ephesians this coming Sunday isn’t all that much a detour. Note Paul's link to shepherds in Ephesians 4:11.We will be discussing the need, significance and importance of developing teachers at CPC in The Hill. *μὲν is usually not translated, however, the μὲν . . . δὲ construction should be understood as “on the one hand . . . and on the other,” thus my translation. Furthermore, each δὲ in the string strengthens the reading that each office/role is included with the epexegetical καὶ (namely, that are).

“. . . but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matthew 10:6) There is an interesting nuance to Jesus’ commission to the twelve in Matthew 10: When Jesus instructs them not to preach and heal and cast out demons among the Gentiles and Samaritans, he, however, specifically directs them to “the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10:6). Again, this seems a verse we read (into) as another “everyone” text, that is “go to everyone in Israel for all of them are lost sheep.” Let’s reconsider: The word Jesus uses for “lost” here in 10:6 isn’t rendered at all very well by English translators. It is a specific word and no-where does it actually mean “lost” the way most of us modern Christians read the word and certainly doesn't carry the weight of a religious overtone of “lost” as in unsaved. The word is ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi, destroyed, banned is actually a good word). As this word is used (and rendered) elsewhere in the NT, a more consistent translation would have been “go rather to the destroyed sheep of the house of Israel.” This nuance changes how we read this charge to the twelve. If the English “banned” (a fair rendering as we shall see) is used, the resulting condition is nuanced to description, namely, of those “who have been shunned to destruction.” In fact, there is even more nuance to be heard from the word and the context. Previously in the immediate paragraph, Matthew depicts the scene in which Jesus has been ministering to the sick, outcast, marginal, disgraced, and poor (9:35). Jesus looks upon this crowd, Matthew narratives, telling us that He “he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd” (v. 36b). There is no doubt Jesus and Matthew are drawing upon an Ezekiel context where God interjects, “So they were scattered, because there was no shepherd” (Ezek 34:5). Yet, just before in 34:4, the people, i.e., the sheep, carry the same conceptual (sociological) description as does Matthew 9 and 10 regarding the condition of certain Israelites, i.e., “the lost sheep of Israel”:

Additionally, as you can see in the brackets above, the LXX OT (i.e., the Greek OT) uses the word ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi, destroyed), the same word use by Jesus in his instructions to the twelve in Matthew 10:6. English translators (virtually all) render this word in Ezekiel 34 and Matthew 10 as “lost” (as in “lost sheep”). In both Ezekiel and Matthew, this strong word gives a very subtle description of the people as vulnerable sheep who are “put out of the way entirely, abolished, destroyed.” Elsewhere in the New Testament, this word, ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi, destroyed), is used to give a rather dire description of a person's condition as a result of the actions or behaviors or attitudes of others.

The more accurate rendering of “lost” as destroyed (ruined, banned, shunned) helps to further see an actual sociological condition in the use of “lost sheep” to describe people or a person. In Luke for example, the treasured images of “lost sheep,” then, brings out (for significance and application) a rather different imagination regarding those that are in a condition of “lost.”

In Luke above, we can, then, see that the lost sheep are left alone, unprotected, vulnerable to the elements, lions and tigers and bears (literally), and is, thus, in the condition of “destroyed.” Jesus juxtaposes the restoration given by Zaccharus with His own mission to seek and to save the destroyed, the banned, the shunned. In this latter text, Zaccharus' own salvation is related to making people whole since he contributed to their condition of “ruin" (of being banned, shunned, destroyed). Now returning to the “the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (of Matthew 10:6), we offer a more sociological-rhetorical reading of the verse. While apollymi (“lost” as rendered in most English transitions) in v. 6 certainly is a strong word and “destroyed” is perfectly acceptable as a translation, we should also note that this is the word used to describe those who have been banned from synagogue. Also, the raw, wooden transliterated meaning of this word, apollymi, literally means “from let loose,” “let loose from,” “unloosed”). This is most certainly its meaning later when the local synagogue leadership in Caperneum made plans to “destory” (i.e., ban) the man whose withered hand Jesus had healed: “But the Pharisees went out and conspired against him, how to destroy [apollymi] him” (Matthew 12:14). [Whether the antecedent of “him” relates to the healed man or Jesus, the implication is to be banned from the synagogue.] Finally, given the nature of Jesus’ primary audiences thus far and Matthew’s summaries of His ministry (4:23-25; 9:35-36; et al), perhaps we should read “lost” as “banned sheep of the house of Israel,” specifically identifying the marginal, infirm, mentally unstable, demon-possessed, poor, outcast, and disabled sheep of the house of Israel—all whom would have been shunned away from synagogue life, not just figuratively speaking, but banned from the worshipping and religious life of Israel. Is it no wonder the temple-leadership did not like and was angered (or is that threatened) by Jesus' association with tax collectors and sinners? Leveling and equalizing the idea of “lost” in the Gospel narratives to simply a “we all are sinners in need of salvation” (albeit true, of course) places a barrier to faithful readings that put the poor and the marginalized of society in the purview of sound application in the life of the church (a church).

Let’s reconsider two Biblical thoughts from our favorite-to-quote-bucket–“take up your cross” and “Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 10:38-39)–and see if we can save them from the pile of Christian clichés. We should pay closer attention to the narrative context as we read the text from which these two are found, before we make application: that is, hearing the significance, then making application. Taking up one’s cross is often used devotionally to move Christians toward obedience; and, losing-finding one’s life is often used toward the nonChristian to draw them to Christ. Not bad things (or outcomes), but rather than a general (privatized) application of these–which, by the way, these are toward Christians for faithful perseverance and endurance in the faith, which is the context, e.g., “. . . the one who endures to the end will be saved,” 10:22b–and, thus, a more specific application is warranted. First, the context is specific:

The immediate paragraph context is the strain and conflict between believing and unbelieving household members. Household conflict in general would have threatened heir legitimacy (the reason for the household in the first place in Greco-Roman culture and social construct, to produce and protect a legitimate male-citizen heir), the passing on of wealth and family social standing, and would have put at risk one’s survival . . . so literally one “saves” one’s life through the family/household and “loses” one’s life apart from family (that is, a household under a patriarch, male-head-of-household). This was the Greco-Roman way (in the time of New Testament). This makes better since of Jesus’ words: “Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 10:39). Thus, taking up one’s cross (v. 38a) is related to what happens when following Jesus puts one, “for Jesus’ sake” (v. 39b), in a place where one can no longer count on the social construct available for life (literally for survival). So, the significance of this text and these “clichés” is, following Jesus (which this text is about; v. 38b) means to die to (i.e., no longer count on or trust) the ways in which our social constructs and cultural norms provide identity, security, and worth. The Christian’s identity, security, and worth is located in Jesus and in his cross, which, then, sets animosity, alienation, and, potential, hostility in within the world (i.e., society and cultural and institutional place) that currently gives one identity. This is truly Christian discipleship, that is, following after Jesus. This is losing one’s life (i.e., giving up, abandoning, rejecting, not trusting in such social norms--again--for identity, security, and worth) to find real, true life through following Jesus. The question would, then, be what social constructs and cultural norms give us (give you) identity, security, and worth? These we need to die to in order to have real, true life. This is what it means to actually follow Jesus.

Some exegetical fun with Matthew 3:3: The ESV and almost every Bible version I can find translates Mat 3:3: “The voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord; make his paths straight.’” The Greek is pretty close (almost dead on) with the Isaiah 40:3 of the LXX (i.e., the Greek translation of the Old Testament): φωνὴ βοῶντος ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ ἑτοιμάσατε τὴν ὁδὸν κυρίου εὐθείας ποιεῖτε τὰς τρίβους τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν (LXX) What our modern Greek version of Matthew 3:3 does (which is reflected in the English translations) is to put in commas where there wouldn’t have been commas in the original Greek Matthew. And, the modern Greek version makes a capital Ἑ (epsilon) to give the impression that’s where the “quote” starts (Ἑτοιμάσατε, “Prepare”). This would not have been the case in the original as well. However, if we leave things as they are (or were, that is), the “quote” could have started (and probably was meant to be understood) at “In the wilderness,” which more accurately follows the Hebrew of Isaiah 43:3: A voice cries: So, John, as Matthew probably intended, was more likely heralding, “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord!”

Why is this important? Because this, (i.e., “in the wilderness,” “in the desert”), is where God’s royal road was to be built (cf. Isaiah 40). The “desert” (the “wilderness”) is the prophet’s way of referring to the chaos of the uncreated world of Genesis 1:1 and the condition of the land now inhabited by people that had returned to “chaos” and darkness, a land lacking water, a dry place (spiritually and actual) where God must recreate. Jesus is introduced into a place, a desert (if you will), where he will recreate a people for his Father’s glory. Both Isaiah and Matthew are drawing upon this Genesis creation. This is church. This is church planting. This is more, an intentional church planting in the hinterlands, as Sean Benesh wrote, in “the uncool places.” “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord.”

For some reason, I decided to translate and soak in Galatians 2:20 this morning. I have given it a different spin (than most of the translations and how it is all too often preached); yet, the rendering is both grammatically justifiable and faithful to the biblical theology behind “in flesh” (ἐν σαρκί) and “in faith” (ἐν πίστει). Below, the first is, more or less, my word for word translation (with some help in brackets), which is far more fun to read out loud (to really hear Paul’s audible impression), which would have been the way the first hearers heard (they heard, not read) it. Below my wooden translation, I offer a more English interpretive translation for you.

My interpretive translation:

For why I have taken the last line in v. 20 as I do, check out what Paul already wrote in his introduction to Galatians: “. . . and the Lord Jesus Christ, who gave himself for our sins [cf. Gal 2:20c] to deliver us from the present evil age . . .” (1:3-4). Furthermore, the simple two words "But now" (δὲ νῦν) imply the inauguration of the new age (i.e., the kingdom of God) has come in the appearance of Jesus. Of course many times “now” simply means “now.” Paul, however, often uses "but now" to indicate the inauguration of the new age that has arrived in the coming, cross, and resurrection of Jesus Christ and not simply as a conjunction (cf. Gal 3:21; Rom 3:21; 6:22; 7:6; 8:1; Eph 2:13; Col 1:22; cf. Rom 3:26; 11:5, cf. “in the now time,” ἐν τῷ νῦν καιρῷ). Thus, Paul is helping the reader to hear that these words within the tension between this present evil age and the age to come inaugurated in Christ. To be crucified with Christ is to be delivered from this "present evil age" and, thus a participant in the new age, now. Seems to me this verse, Gal 2:20, calls us to live a life based on the new age hushered in by the Spirit (i.e., the new age of the kingdom) that was inaugurated in Christ’s faithful action of the cross (the reason Paul says, “I have been crucified with Christ,” 2:20a, which centers on the cross); rather than living by the passions and systems of the flesh that make up the way the world around us works (cf. the fruit of the flesh vs. the fruit of the Spirit later in Gal 5:16-24). This text reminds us, as Christians and as church, we are wholly different. Very much like Jesus’ words in John 17 that we are in the world, not of the world. This goes with the church-problem that Paul seems to be addressing, that is the nature of the gathered-church. Paul illustrates this by his previous rebuke of Peter (cf. Gal 2:11ff.), who, for whatever reason, had separated himself from Gentile believers at the table (probably a reference to the Lord's Supper of the gathered-church). Additionally, Gal 2:20 is not far from the implications of Paul's words in Ephesians 2:11-22: note the centrality of the cross (i.e., crucifixion as the means by which the wall (i.e., separation) is broken down between believing Jew and believing Gentile, making the two (literally, the both) one new humanity (in Christ), which is the household of God, being built up as a holy temple (i.e., the gathered-church). Therefore remember that at one time you Gentiles in the flesh, called “the uncircumcision” by what is called the circumcision, which is made in the flesh by hands— remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made us both one and has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility by abolishing the law of commandments expressed in ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby killing the hostility. And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, in whom the whole structure, being joined together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord. In him you also are being built together into a dwelling place for God by the Spirit. To be crucified with Christ is to be caught up with the Spirit's working in forming the church. In particular, intentionally, a church, to fulfill the principle of being "crucified with Christ" ought to reflect the age of the Spirit wherein "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Gal 3:28; cf. Col 3:10-11, "new self" is actually "new man").

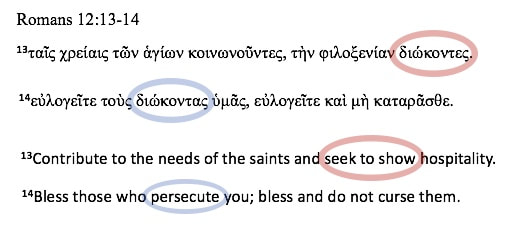

Working on Roman’s 12 for Sunday. There is a little creative punning by Paul in his Romans 12 (ESV). Most think of a pun as some form of joke or humorous quip; however a pun is a word-play, also called paronomasia. A pun can be both visual (the form of the word) and auditory (hearing), a form of word-play that suggests two or more meanings played off each other for rhetorical effect, harnessing the multiple meanings, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. Here in Romans 12, Paul uses such punning to emphasize the importance and significance of the gathered-church. “Contribute to the needs of the saints and seek to show hospitality” (v. 13). Here is my own translation, which reflects Paul's original word order and the reading of it out loud. Sometimes hearing it is the best way to catch the intent: “The needs of the saints, contribute; hospitality, intentionally pursue. Bless those who persecute, bless and do not curse” (Rom 12:13-14). Three things worth noting:

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed