“And on that day a great persecution began against the church in Jerusalem, and they were all scattered throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria, except the apostles” (Acts 8:1b, NASB). “Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To those who reside as aliens, scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, who are chosen according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, by the sanctifying work of the Spirit, to obey Jesus Christ and be sprinkled with His blood: May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure” (1 Peter 1:1-2, NASB). ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ ❉ Imagine. If you can. You are a small gathering of Christians in the first century. The new born church that we meet in Acts, now scattered throughout the Gentile world. A very minority church in the Roman Empire up to about 150 C.E. By now, most of Christian fellowship, instruction, and worship was done in homes, catacombs (underground cemeteries), workshops (that were also apartments) or hidden away, or above the streets, in tenement-styled, stacked row building apartments. Imagine. The “gathering together,” what we could have called “a church,” is still illegal, at least not recognized as religio licita, a permitted cult or religion in the Empire. Imagine. That fourth and final cup after the meal was over (Luke 22:20; 1 Corinthians 11:25), still treasonous, lifted, now not to Caesar, but to honor Jesus, risen and Lord. Gathering together was still very dangerous. A non-domestic building, set aside for Christians to gather for worship, was still many decades off, probably 200+ years in the future. The earliest separate building devoted to Christian use was in eastern Roman Syria at Dura Europos on the Euphrates River. Originally a house that had come into a Christian's possession and was remodeled for church gatherings in the 240s CE. But still, it wasn’t like church buildings were popping up all over the place after Dura Europos. It would still be another century before non-domestic buildings would more readily (and permitted to) be built or designated specifically for gatherings of believers to function as a “church building.” And, still, even around 350 CE, there won’t be a boom of church buildings going up everywhere.

We, too often, work backward from our building-experienced-church to the New Testament, imagining the church we read of in Acts (and Romans, 1 Corinthians, Philippians, et al.) or read of the first century church as being all made up of these small groups of somewhat organized believers that gather (albeit) in homes as if they are free to do so often, let alone, weekly. Yes, of course this happened. Just not as neatly as we imagine. The church of Acts and the early (first century) church is far more scattered, less free to meet, than we imagine. A clandestine church is more likely a better way of thinking “church” for the first 150 years or so. We simply do not have an imagination of the church as revealed in the New Testament. Why is this important? First, it, that is, the house-church, is how God choose to reveal what He meant by church, a gathered-church. Yes, the difference between “form” and “element” is important; but form develops habits that sneak in to determine element. The form of the New Testament house-church developed habits that taught something about the nature of church as do separated buildings teaches something about church. And, secondly—and to the point in this piece—churches in the New Testament and in the early church didn’t have the privilege of a legal means of or a culturally acceptable means to gather once a week on a day that is (like our Sunday) a “day off” in what would be, more than a millennia off—something come to be called a “weekend.” Today, with this COVID-19 crisis, what we have is a very non-ordinary time. For us, here in America, at least. For quite some time, we have been pretty much guaranteed the freedom to gather together as churches. And boy do we. All types of church. Big. Medium. Small. In all types of buildings. While there are some home-church movements, most church congregations meet in separately addressed, non-domestic buildings of some kind. Yet, still, even now, there are many churches throughout the world that do not have the freedom to gather together—some because they are oppressed; some because they must hide; some because there is no such thing as a weekend; and, some are simply too poor and exist in under-developed or third world nations (or, even, neighborhoods).[§] These churches are much closer to the young church than we can imagine. But, we are beginning to imagine. Still, it is hard to imagine a church as a “scattered church.” However, I believe we need to have this imagination now.

We also need to understand that these “scattered” would not have had “churches” to move into, or established fellowships to embrace, and no places into which they’d be welcomed as “churches.” They were indeed “scattered” without (at least immediate) access to the Apostles (who stayed in Jerusalem, Acts 8:1)—which would have meant no communion (as we know it), no qualified preaching or instruction from the Word and/or Words of Jesus, et al. Indeed, they were scattered. In the 1 Peter passage, we have a church that is described as geographically “scattered” throughout Asia Minor. And, of course, this “scattered” are small household-churches, gathered together, but still, we need to embrace the term “scattered.” This text, also, tells us that nothing is lacking in this “scattered” church. Though “scattered,” these household-churches were chosen (aka, the elect); all are completely caught up in the sanctifying work of the Spirit; all are charged to obey Messiah Jesus; all fully sprinkled by His blood (i.e., made pure). This spiritual equity is also pointed to in the blessing that Peter immediately brings in his address: “May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure” (1:2d). The whole of Peter’s first letter describes a church in crisis, amidst culturally formed suffering: “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you” (4:12). This affirms that a “scattered” church is a church responding to crisis, under some form of suffering, threat, and/or pressure beyond its control that disrupts everything for them. Of course the word “scattered” is a pun on the Jewish Diaspora (i.e., the scattered ten tribes of Israel). Yet, this pun works because the young church (or better, young churches, plural) existed in a hostile environment, one of (at least local) persecutions, where their neighbors, families, and whom they commerced with, all hold to a polytheistic worldview, and in a surrounding culture that is all about legality (i.e., being considered a legal citizen with standing before the law), blood legitimacy, and social standing (i.e., honor). What is interesting, this pun, being called “scattered” is indeed like the Jewish Diaspora, which had no temple and living as aliens in strange lands (i.e., the idea behind “resident aliens” of 1 Peter 1:1b). This is “scattered” church. This last description is important, for scattered Israel in and throughout the Greek-Roman world had to learn to be God’s people in a time and in a land not formed by their religious values and habits. In a foreign, strange, alien world. In a land where they had little to no control or power over their religious habits. Prayer and the Word became very central to scattered Israel. Even non-Diaspora Jews (what we mostly meet in the Gospels) were, as well, not in control of their religious habits. Sure, they had the temple, but it was tolerated and governed and watched over by pagans (aka, outsiders, polytheists, Caesars, haters), who only tolerated the people of Israel (not who accepted them as equals).

I don’t think we could have imaged, even three months ago—or even for that matter, ever—that we’d be “ordered” (or pressured) to not gather as churches. To be cut off from our buildings that offer take-for-granted habits we interpret as biblical and essential to understanding “church.” To be separated from other members of our own congregations that plays tricks on our assumed biblical concept of “church.” This is a time for our imagination of church to include being “scattered.” This imagination will prepare us for the (real) trials to come. And you need to understand, this is not the trial, but only a preview of what is to come. Someday. Three months ago, we would not have thought it possible to be at this place, being his “scattered” people, a church not in control, regulated by outside pressures and forces, unable to freely meet together. It is of note, especially with regard to the “scattered” nature of the church in 1 Peter, that, as a “scattered” church, the test or trial is not solely one of individualized faith. As a “scattered” church, what is being tested at this time is loyalty (the actual meaning of the word “faith,” πίστις, pistis). Are we loyal to Jesus and are we loyal to his body? And, by “his body” (aka “the body of Christ”), I do not, as I believe the New Testament writers do not, mean some notion of a universal, invisible church, but loyal to a local body of Christ, consisting of actually flesh and blood fellow believers. An imagination of “scattered church” will help us to learn new habits that build the body, that strengthen our fellowship of believers, and, very importantly, habits that proclaim in Word and deed that we are followers of Jesus, so that, publicly, others will know that we are Jesus’ disciples (John 13:35). We are, local and in all locales, a church in crisis. Right now. And, this makes us “scattered” churches. We endure, although scattered, yet together in Christ, so that perhaps, through our suffering, God’s elect [wherever our “scattered church” exists--for us, the Hill] may obtain the salvation that is in Messiah Jesus (2 Timothy 2:10). Let us remember, as “scattered church,” we are no less church. We are the full-body of Christ, though scattered. We do not lack anything from God as a scattered church. Even now as scattered church, the blessings of Peter is completely ours in Christ: “May grace and peace be yours in the fullest measure.” [§] A Third World country is a developing nation characterized by poverty and a low standard of living for much of its population.

0 Comments

IV. The “Inner [One New] Humanity” Temple (aka "Inner Man") and the Revelatory Nature of the Church There are enough hints, allusions, word plays, and inferences to draw the conclusion that “the saints who are at Ephesus” (Eph 1:1) are indeed God’s temple (2:18–22; 3:6, 8–10, 14–19) in contrast to the plethora of pagan temples in the region and who are the fullness of God in Ephesus et al. They are God’s temple, with Messiah Jesus as its cornerstone (2:20), a building created and being built, not by human hands (2:11) of stone, wood, and metal, but by God’s words, through his apostles and prophets, made effective and filled with his Spirit, ever expanding, right there in (a) place (and the next place and then the next, etc.). The church (a local church) is being built as a house-temple to reveal the mystery of God’s reconciliation work in Messiah Jesus (Eph 3:5–10; cf. 1:9–10; 2:10). The reconciling work of the cross becomes the reconciling of flesh (i.e., people and systems and institutions, 2:11–16; 3:10; 6:10-15) in (a) place; the deconstructing of social and institutional powers, heavenly and earthly (cf. 1:10). The local church, as God’s temple where his fullness is housed (dwells), is to be a revelation of God, his mystery in Messiah. Set in contrast to contemporary (ANE) “temple” life, a corporate inference to Paul’s “inner man” seems most reasonable. In the previous paragraphs (Eph 3:1–13), Paul frames the following prayer (vv. 14–19) by, first, explaining the nature of his ministry and of the church as the revelation of the “mystery of Christ,’ which he already had alluded to as the “one new humanity” (2:15c), the incorporation of the Gentiles into church(es) (i.e., the promises of Christ through the gospel,” 3:6c). Thus, a fair reading of Ephesians 3 as a whole suggests that the church (a church) itself is a revelation of the gospel. Understanding the polemical temple backdrop to which Paul utilizes, there is further reason to read the revelatory nature of the church (a church) as appropriate to grasp the intent of his Ephesians 3 prayer. In other words, the church (a church) is a “thin place” where the mysteries (i.e., the revelation of the gospel) is revealed. The “thin place” is that sacred space, the place where the unseen mysteries of the heavenlies and the concrete places of the earth touch, cross, meet. A thin place is where one can walk in two worlds at the same time, the two worlds fused together, where the differences can still be discerned. As someone explained: “A thin place is a place where the boundary between heaven and earth is especially thin. It’s a place where we can sense the divine more readily.” This is why Paul prays as he does for the “saints who are at Ephesus” et al in verses 14–19 and offers the benediction in vv. 20–21 concerning ekklesia and all future generations of churches. The “one new humanity” (Eph 2:15c) is the very expression of the temple, the inner sanctuary where God is housed, where he speaks, and is revealed. The “inner man” (more so, the inner humanity) that is gathered in house-temple-churches (literally, in the homes and at the supper tables) are the revelation of the gospel of Christ. The church (more so, a church-gathered) as God’s temple is this “thin place.” V. The Corporate Church Implications: Revelatory Church Growth Outcomes 1. The habits of church life need to move away from the building-centered experience to be the church in (a) place: i.e., non-building-centered outcomes to determine church growth (it is the reconciling element of the cross among people that is being joined together and growing into a holy temple in the Lord, that is being built together into a dwelling place for God by the Spirit (Eph 2:20b–22): God’s new revelatory temple. 2. The habits of church go counter-cultural, moving away from a privatized Christian experience toward a corporate application of what it means to be the church in a place, a gathered-house-temple, with a concrete home (a neighborhood) address, where strangers and unequals (note the reconciliatory aspect I am suggesting) participate as church around a supper table [unlike a building-centered church experience, where neighborhood is absent]. 3. Since the stress is on the inclusion of Gentiles as fellow heirs and fellow-partners with believing Jews, part of the church’s revelation exists, as a gathered-temple/church, to be a visual (flesh of a neighborhood or community) that demonstrates reconciliation outcomes (based on Ephesians 2:11–22 and 3:1–13). 4. Church growth outcomes should reflect the realities of what it means to be God’s temple in (a) place: Outcomes measured in the language of neighborhood, reflecting the reconciliation of actual people (i.e., strangers and unequals, etc.). 5. Church growth outcomes should reflect the decision-making that removes barriers to accessing the Father and promoting what draws people into free access to the Father (as opposed to accessing a building). 6. Think cosmologically. Act locally (develop outcomes related to the local neighborhood and wider community).

#churchmatters: Gathered believers are sacred space (not the room or building they meet in)5/27/2019  “The church (read a gathered-church) does not need a ‘sacred place’ to worship, have fellowship, and to offer (apostolic) instruction–three things the apostolic and early church would not have separated–for those gathered are the sacred space. In fact, the local gathered-church is the liminal space between the heavenly places and earth; the human beings, who have gathered together, are the most sacred space, the holy of holies as it were (literally), in all of creation at that moment; they are, not the space or place, the address, they occupy, the temple of the Most High, the Creator God of all creation; they are the mystical, yet visible body of Christ, that is, the presence of God in Christ on earth, right there, because their ascended Head, Messiah Jesus, is now seated at the right hand of God in the heavenly places and they, these gathered believers are His body” (CMA). Church matters (#churchmatters)

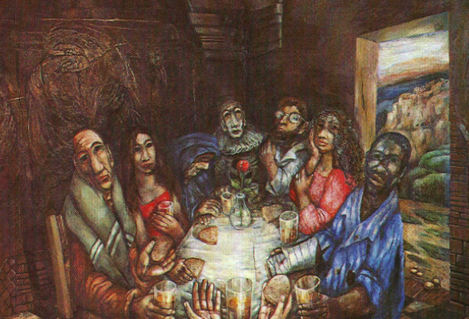

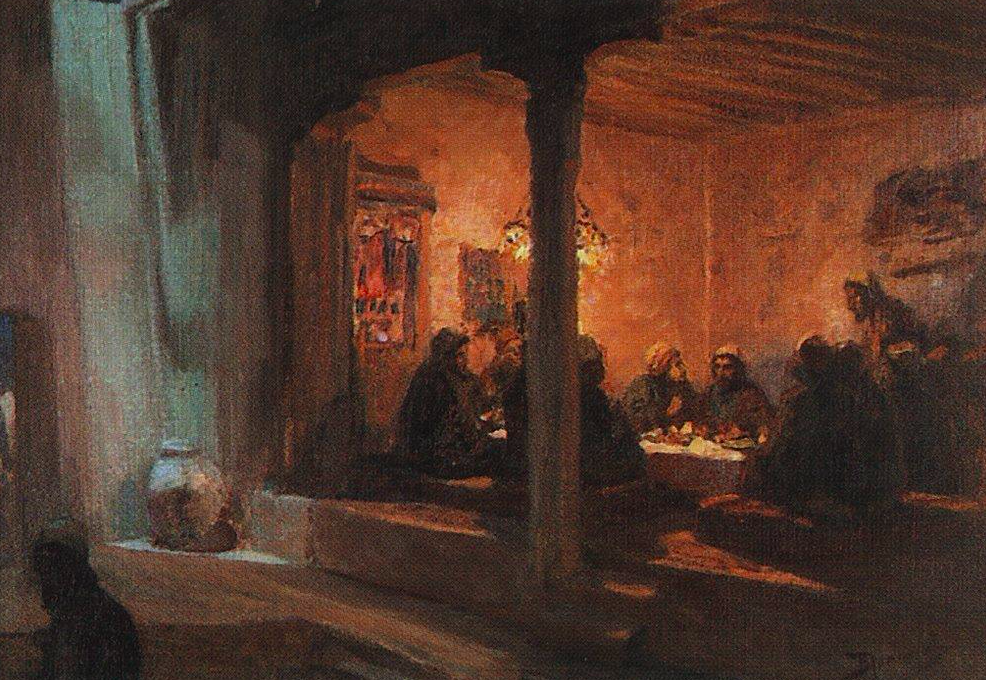

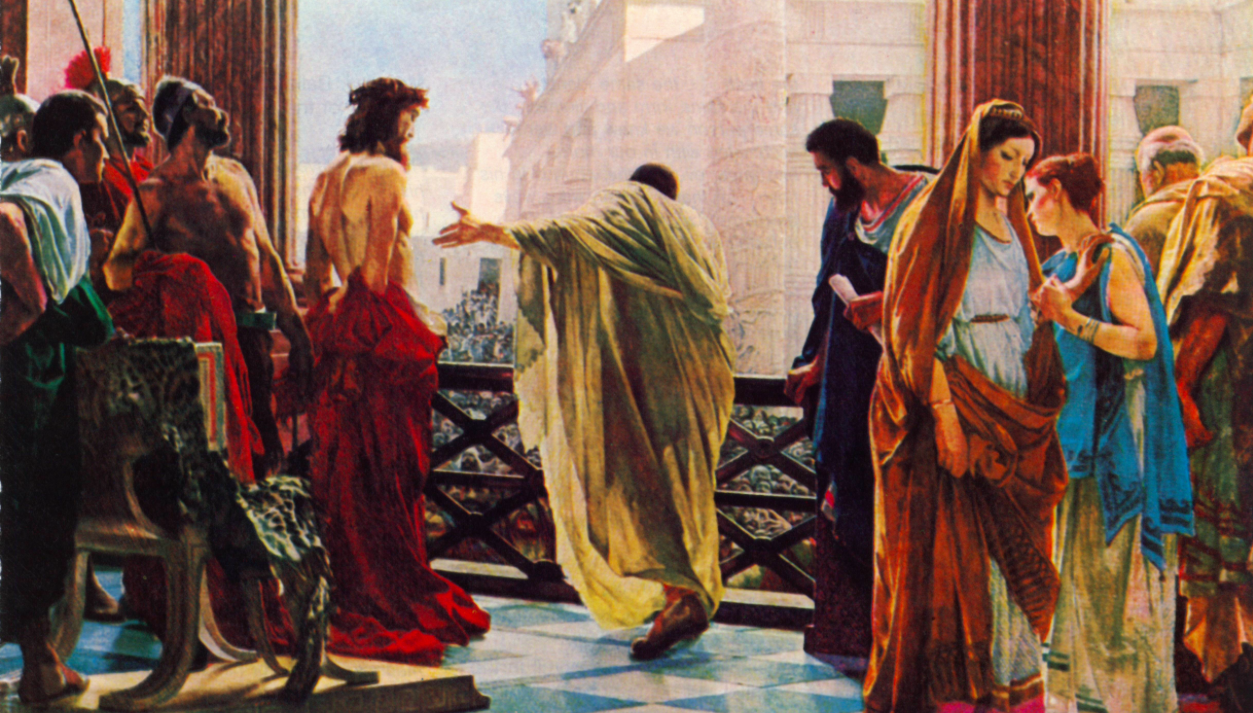

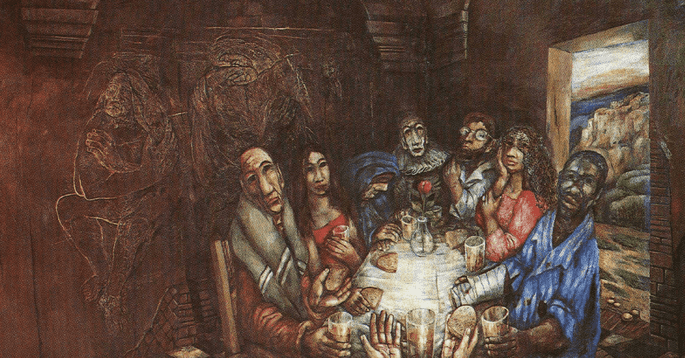

There are so many grand and wonderful paintings of early church times of table fellowship. And some I really, truly like. Yet, there is a male-centerness to them that would not have reflected the actual tables of Christian fellowship of the early church that these scenes are to depict. I do not see women and wives and slaves and children; typically just men, and when women are depicted, they are serving food. Most of these grand paintings were created and come at the time after Constantine, the Roman Empire Caesar (272 AD - 337 AD), herded the churches away from the homes of Christians and into buildings sanctioned by the State, along with laws to build up and protect an appointed church authority and priesthood consisting solely of men. Church began to reflect the culture of the empire more so than the one painted by the Apostolic church and the early church through 300 AD. This move recreated church away from the Table fellowship of strangers and unequals that had increased and spread since the days after the Pentecost of Acts 2. Most of these wonderful paintings, as far as I can tell, come from the post-constantine Christian era, reading their “church experience” back into the apostolic and early church (form and experience). We do that, too, now. We start with how we do church now and read it back into the New Testament accounts and teaching--this anachronistic. Our vision of the church not only reflects the flaws and the unredeemed aspects of our social and cultural times (and trends), but we read this experience of church back into the life of the early church and, worse, back into the vision of the church depicted by our New Testament writers. We need to do better.  The passion week scene of Jesus and Pilate has provoked many thoughts for me as I prepare for this year's Easter season. I mentioned in a previous post that we ought to identify with the readers of this story and listen closely as they would have to John's telling of this story, and in particular the scenes of Pilate and Jesus (in John 18-19). This scene was an answer to them, as it still remains an answer for us, this is how things change–this is God's way to change the world, destroy powers, and save humanity (our friends, family, and neighbors, even our enemies). Looking to Ephesians for a moment: I am persuaded that the Gospel of John was written by John in the Ephesus area and its first audience was the gathered-churches throughout western Asia Minor (similar as Paul's Letters to Ephesians and Colossians). So, I start with Ephesians. Most take Paul’s Ephesians letter as an issue-less document (e.g., no real problem in the church) and crafted in such a way to address the church universal rather than the church local. Nonsense. Absolute nonsense. The Letter was written to the local churches—ye, household gathered-churches—throughout western Asia Minor . . . and given Ephesian's highly liturgical and hierophany-like nature, its temple-ish and sacred space framing . . . I take the issue to be: the gospel had so penetrated into the Gentile world that former pagan-temple worshippers entering into church fellowship needed to learn a new temple-life as church, something wholly different that there temple life in Roman, pagan culture and society. In this case, a gathered church that looked and felt more like a living room filled with unequal strangers, wives and husbands, children and slaves, and extended family . . . than a theater-like building with mostly equals sitting in pews . . .  What would this scene, Jesus before Pilate, mean to the young church of mostly former (and some, for sure, still) temple-worshipping Gentiles and a number of Greek-speaking diaspora Jews living in western Asia Minor? We must acknowledge and grasp that there is no New Testament analogy for what we do on a Sunday morning. We’ve exchanged someone’s dining or upper room in the greater Ephesus or perhaps Laodicean region for a theater-like building that Caesar (now) sanctions. We have exchanged a meal, a diepnon or supper, with the broken break shared at the beginning of the meal to signify all those gathered at table were in Christ, a family, made one because of Jesus’ broken body on that criminal’s cross (cf. Eph 2:11-22) and where a cup would be raised after the meal (cf. Luke 22:20) to honor, not Caesar or a household deity, but the resurrected treasonous-traitor, Jesus, the real and only King of kings and Lord of lords, the One standing before Pilate–all exchanged for tokens and symbols rather than a gathered-church of unequals and strangers, poor and wealthy, beggars and doctors, the discarded and the elite, the temple prostitute and the patron, slaves and masters, orphans and male child-heirs, girls and children of slaves, women and men . . . this was the way to destroy the gods of the Greco-Roman empire and to topple a Caesar. There was only one king in that judgment hall. The one wearing a crown of thorns, bloodied by a criminal's beating, fist marks on his cheeks, in a mock purple robe. You see, we hear the passion-week inquisition where Jesus stood before Pilate with strange ears to the story . . . but . . . hear again we must . . . again, differently . . . we must cry out, 'We have no king but Jesus!' and abandon all our idolatries and allegiances to the kings and powers of this world. As it was for those early gathered-churches in western Asia Minor, so still for us: this is how God destroys the powers and changes everything. All the Wasted Passion Week Thought blogs >> Click Here

Among most protestant, evangelical churches we say our worship isn't mediated via a priestly order or professional; but isn't that really how, for the most part, congregations experience worship? The original New Testament church and on into the first 150 or so years met in homes and worshipped around a regular household meal, which helped promote, facilitate, maintain a connection between faith and life as a whole. A separated worship began the process and habits that produced a dualistic spirituality in our faith—one for Sunday and one for the “real world.” When the building (a building) is considered the liminal* space between God and people, a dualistic religious experience is established and maintained through continued use and habits associated with the building (a building). In other words, “Church is conceived as a sacred space; the ethereal architecture, lighting, music, rituals, religious language, and culture all collaborate to make this a sacred event not experienced elsewhere in life in quite the same way” (Alan Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways, p. 103).

Of course, there was a progression and a modification of household worship over the first 150 to 300 years of the early church. But it was Caesar, Constantine specifically, that gave us our start in church as building, away from households. He, not only designed the first separated and built churches, he ordered and approved a professional clergy-class to maintain Christianity under Caesar, and, even, made heresy punishable by the state. Later, under emperor Theodosius such Constantinianism church-forms were strengthened and codified, creating a church culture apart from the text of the New Testament and apart from the household, setting a course for developing a corpus Christianum that affirmed the church’s place under the emperor, and declaring Sunday as the official day of religious “church” observance with obligatory attendance and, as well, punishment for noncompliance. Most of what we see, experience, and affirm in our church experience is a long by-product of Constantine and the long-standing power invested in a professional clergy class. For sure, there are positive benefits for such a clergy, that is the maintaining and protection of the gospel itself and for preserving a tradition; yet, as in all social experience wherein a guardian class is created (or needed), power becomes the necessarily element in maintaining its (understanding of) purity and rightful inheritance. And, at least in part, the building-centered system we have is a means to protect the rightful inheritors of ecclesiastical power. This, then, becomes part of the building-centered church experience for the congregation, further teaching by habits and world (i.e.,religious) view a dualistic spirituality that separates the sacred from the secular.

When we, that is leaders of the church, are puzzled over, saddened by, and, in too many cases, judgmental of lay-Christians who do not apply or live out their faith in the ordinary, profane, and mundane life outside of “church,” we should not be surprised, for we have taught them to live and experience their faith in this way. When we, by affirmation and by our habits, designate a building as liminal sacred space rather than, as it seems, God's people are now to be such sacred space, we teach our congregations to have a dualistic faith.

*Liminal, that moment or space between earth and heaven, the entrance or threshold between the ordinary or profane and religious or sacred. “The Pharisees and their scribes began grumbling at His disciples, saying, ‘Why do you eat and drink with the tax collectors and sinners?’” (Luke 5:30). Was struck this morning in my daily Bible reading concerning the phrase “tax collectors and sinners.” If we, that is the church (the body of Christ) that is now the presence of the ascended Jesus (that is his body in a place), how is it that we (not as individuals, which is a wholly modernist and ‘merican notion of church applied to the nature of the Christian life, i.e., replacing “wēs” with “I”) are not at a place--in a space--where we are accused of “eating and drinking” (there’s the idea of meals again) with “tax collectors and sinners”?

Instead, we are safely tucked into a building designed and with habits to distinguish who's in and who's out, where all leveling is errased, and we have power over guests; a place where we can escape being aligned with the “Son of Man” and being maligned as a gluttonous group and drunkards, friends “with tax collectors and sinners.” And, gathered in a space that is, in many places, not at all welcoming (easily accessible by design and by default) to “tax collectors and the sinners” to come near to find Jesus and to listen to him. Now such association with the likes of these people and populations, that is the equivalent to “tax collectors and sinners,” is relegated to church programs outside of the practice (i.e., worship) of the body, to specialists and volunteers, and carefully guarded and designed events. (Don't get me wrong, I know it is important to have worship time—but the early church met in homes that allowed for a mixture of believing and unbelieving to be present, both around the table and within eye-sight and ear-shot.) I am impressed, however, with the idea, amid the wider reading of the New Testament, that this is a church problem, not a volunteer or scheduling problem. These texts (and way too many like them, e.g., Matthew 9:9–13) are ignored as texts to be applied to the body of Christ (local). How does the body of Christ, not individual Christians severed, apart from the gathered body—on their own time and amid their own convictions and conscience and resources—but, the church be Jesus in this way so that “tax collectors and sinners” are seated at the table in his midst? Perhaps, then, we will, once again be accused of eating and drinking and associated with the marginal and despised, tax collectors and the sinners. Rethinking church. Just finished the long exegetical section on Ephesians 5 command to be filled in Spirit for my up-coming November Evangelical Theological Society paper . . . some editing I am sure, but drafted! Here is the summary for those interested:A contextual-exegetical exploration and summary places the Ephesians 5 filling command within the sphere of God’s new temple-church (Eph 2:19-22). The community of believers is God’s new sacred space, his multihousehold temple-church that is a dwelling place of God in Spirit, which is a reflection modeling of God’s cosmic reconciliation. Herein lays the potential importance of the following household code: the relationship-trio (wives-husbands, children-fathers, slaves-masters) must in someway indicate the architecture of the new temple, first, as the space where the cosmic reconciliation begins to expand, but also, second, in demonstrating the subversive nature of the work of God through the Messiah in reordering the basic unit of society under the new paterfamilias, the Father. The household code, then, offers trajectories of significance for church growth outputs and outcomes. The relationship-trio, somehow, pushes us to reimagine church growth beyond mere numbers of people in a “sanctuary” built with human hands; potential outcomes that require evangelistic outputs (i.e., activities) that are meant to subvert the status quo and, as a result, demonstrate a reordering reflective of God’s cosmic reconciliation. *For those following my thoughts on "Church Growth" as I prepare a paper for the upcoming November 2015 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta. Other Not by the Numbers posts >>

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed