Trajectory Application: Two NT Case Studies that Address Tyranny and Oppression (B) The curious case-study of Philemon and Onesimus. The story of Paul, Philemon, and his run-away slave, Onesimus, is as close a NT case study there is regarding how the gospel applies to slavery. The primary objection of some, however, is that Paul wasn’t at all clear nor direct (enough) about it. Our comfort level needs unambiguous NT advocacy against slavery and the freeing of “household” slaves. Yet, this would not have helped slaves in the NT world. Some other social, cultural, and anthropological paradigm shifts needed (and in many ways, still need) to change first—a revolution striking at the heart of tiers of human hierarchy. As was the Greco-Roman world of Paul’s day, advocating for emancipation of slaves can be more about our “enlightenment” than about a slave’s (i.e., a person’s) inherent value, dignity, and equality.[1] Nevertheless, based on the household gathered-church and its habitus outlined thus far, Paul seems to have had something much more ambitious in mind than instructing Philemon to simply free Onesimus. A runaway slave was the most vulnerable of all, a de-housed situation revealing all the aspects of the subhuman caste: any protection in society is absent, confirming Roman citizenship is impossible, all ties to a “household” are lost, and, thus, any rights or security the slave would have had are forfeited. Certainly, a female runaway slave faced certain destitution and probably death. If the runaway slave was a male child of the head of the household (i.e., paterfamalia), he would not have been able to “compete” with legitimate children. A slave was most certainly a filius neminis (a son of no one)[2] and this would have been a perilous state to be on the run. A runaway or even a freed slave would go into permanent social subordination or into exile—not truly free. A slave in the Roman world was denied any legal standing--non habens personam (not having a face) before the law. Onesimus’ options in the real world would not have been at all positive—nor free of the tiered hierarchy of human beings. As Sarah Ruden points out, “This is what makes the debate over the letter to Philemon, concentrating on the question of legal freedom, so silly.” Freeing Onesimus directly into Roman society would have put his life at risk. Had Paul instructed Philemon to free Onesimus apart from the slave’s return to the household gathered-church, it would not have worked out well for Onesimus. Paul desires Onesimus’ return to the safest and most secure place, the one space in the Roman empire where the slave would find equal footing—the household gathered-church. First, Paul’s letter to Philemon aligns well within the venue of the household gathered-church, for it was, after all, addressed as well to the church in Philemon’s house (1:2c). Second, Paul’s appeal to Philemon established them both—Onesimus and Philemon—on the same platform (counter to every cultural thought and social boundary): For I have derived much joy and comfort from your love, Philemon, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you (v. 7); and, Onesimus was to return no longer as a bondservant but . . . as a beloved brother (v. 16). This level position is further established by gospelizing Philemon’s own relationship to Onesimus--but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord (v. 16c)—that he would receive his former slave back as Philemon would receive Paul (v. 17b). Fourth, Paul establishes Onesimus’ status in the community of believers drawing upon his state of “usefulness.” Runaway slaves were nobodies and nothing apart from the “household” because they were useless. The value of a slave was pragmatic, utilitarian, and showed the shame of a tiered human hierarchy. As a runaway, Onesimus was not useful to Philemon, however now he was useful to both Paul and Philemon: Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me (v. 11). The scandal was that Onesimus was “useful” because he was a brother in Christ and was to be received as full member of the household gathered-church in Philemon’s home. Finally, Paul further establishes the relationship status, which reflects the gospel, the nature of the household gathered-church, and the equality of those welcome to recline at table: I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment (v. 10). Heirship—sonship and adoption—was established for Onesimus in terms of the faith. Paul was not merely asking Philemon to forgive his runaway-slave, but to embrace him, now, as a brother in the Lord, a full participant at table: that you might have him back forever . . . as a beloved brother and receive him as you would receive me (vv. 15–16). Paul’s appeal to Philemon is in line with NT teaching regarding the household gathered-church and its habitus. The apostle’s approach, a trajectory application of the gospel, was far more ambitious than making Onesimus legally free—a condition in which Onesimus would have been far more vulnerable—choosing rather to affirm his humanity, that is a full human being within the household gathered-church. Paul’s foresight and application of the gospel in welcoming the former slave into the full ranks of membership in Christ’s church, a “son” equal to his former “master” changed everything—and addresses oppression in the company of unequals. Paul is offering a rather subversive paradigm within the seditious gathered-church that is reflective of the Ephesians household-table. The apostolic and early church, without public protests or any actual campaign against slavery, over time weakened the institution and in some places causing it to disappear. [3] The gathered-church is the space God applies the gospel among unequals that eradicates tiered human hierarchies. Personhood. Although it is somewhat anachronistic to speak of personhood with respect to the Bible, it would not be possible to speak of “persons” today, for our capacity to call someone a person is a “consequence of the revolution in moral sensibility that Christianity brought about.”[4] The concept of person had a far more limited function before the appearance of the gathered-church. The Greek prosōpon (as the Latin persona) was not used to indicate “a person” in a modern sense. The etymological meaning is related to a mask (a false face) worn by actors in a Roman theater. The Roman court system picked up the nuance of persōna, a face recognized before the law. In NT times, it was more accurate to refer to one’s standing before the law than to refer to someone as a person.[5] The “role” an individual played amid social institutions helped prescribe Greco-Roman social mapping as it was diffused through the Roman household. Non habens personam (not having a face) was the lot of most women, almost all children, and, certainly, all slaves. However, the presence of Christianity through household gathered-church habitus penetrated the warp and woof of social mapping. Eventually slaves, children, and women became known as persons. Our ability to acknowledge another as person with intrinsic value and worth originates, not only from the gospel as message, but also from the actual habitus that reformed social mapping. The habitus of the household gathered-church, which met for a meal, a kiss, fellowship, celebration, and apostolic instruction, set in motion the redeeming and, thus, reforming of social mapping, ending tiered hierarchies of humanity. [1] Sarah Ruden, Paul Among the People: The Apostle Paul Reinterpreted and Reimagined in His Own Time (New York: Image Books, 2010), 154. [2] Ruden, Paul Among the People, 165. [3] Ruden, Paul Among the People, 168. [4] Hart, Atheist Delusions, 167. [5] E.g., Jesus did not have “person” before Pilate (Atheist Delusions, 167); e.g., how blacks were not recognized before the law as a person prior to emancipation and the ratification of the 13th Amendment of the US Constitution (December 6, 1865) This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

1 Comment

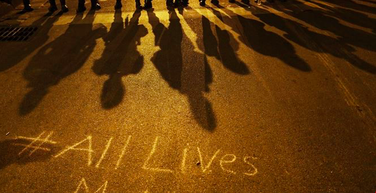

When we hear “All Lives Matter" or “Black Lives Matter," no matter who is hearing the phrase, we tend to hear it politically first, with a whole set of pre-answered assumptions about history, culture, and race, and, as well, with suspicion of some assumed social and/or political agenda behind it. We agree (cheer) or disagree (counter) depending on our own agenda, what we fear, or what we feel the need to protect (or maybe exploit). I get this. It is interesting when Jesus likened the first command to love God with all we got and have, he, then, didn't say, “and love everyone because all lives matter.” No. He was actually very specific, “Love your neighbor.” Of course, we know he didn't just mean the one living next door. Yet saying “neighbor” gave the command a specific definition, even a demographic, and yes, an assumed religious view, which, then, forced everyone to focus on “who is my neighbor?” See—upon hearing the command, it became even more specific. I believe we, that is, Christians, need to reconsider why the hashtag “Black Lives Matter” actually matters (lay aside the political organization here, BLM, and think of actual people) and that we, particularly as Christians, should embrace it. Herein is the issue—for the Christian. You see, the seemingly all-inclusive phrase “All Lives” is not necessarily, well, all inclusive anyway. “All Lives” is predicated on what one means by “Lives” and who fits within its perimeters. In early America, if the framers were to have used “All Lives Matter” instead of “all men,” you can (or should be able to) see why this matters.

Some, in arguing for and defending “All Lives Matter” over against “Black Lives Matter,” make reference that our Declaration of Independence states “all men are created equal.” Although “all” probably referenced “more than just royalty (i.e., the English monarch and royal family), Lords, and magistrates” more than likely “all" reenforced the connotation of those who were being taxed without representation—that is, the colonists in the new world—and not just Englishmen across the pond. “All” gave “men” something specific to reference. However, in the end, there is little difference between “All Lives” or (“all men”) matter and simply “Lives” (“men”) matter. You must understand, it doesn’t really matter what “All” means. Everything rests on what “Lives" (“men”) means—and this is what matters. Nonetheless, at that time, hearing what our framers had written, the hearers would, without any moral compass adjustment or contemplation, understood what was meant by “men” (i.e., “Lives”). Of course, we now affirm that “all men are created equal.” However, not “all men” (i.e., “All Lives”) were actually created equal—at that time. Between the “savages” (i.e., the Indians) referenced later in the Declaration of Independence and, even still later, in our US Constitution and Bill of Rights, that “slaves” were only partially counted (for they were property, not lives), we know that “men” actually did not mean “all living and breathing homo sapiens.” (Which negates the “all” as an inclusive adjective.) In fact, most of the references to “men” (and do notice is does say “men” and not human beings—and don't go generalizing that to them “men” meant “men and women” for it did not as a legal term nor as a socially accepted definition for a person) and the use of the word “rights” had “land-owners” in mind. It would take time for our own US Constitution and Bill of Rights to move past application to simply “land-owners” to women and children and, then, to the general population of US Citizens, and even more time to include “slaves” (i.e., free and bond black and other non-european-whites). It would take time for the idea that “men” (i.e., “Lives”) being property was understood personally and legally as immoral. So, you see, not all “Lives” (i.e., not “all men”) are, necessarily, considered “Lives.” This is why a narrow, more specific, clarifying, preceding word should be embraced. Like when Jesus said “neighbor.” When Jesus had reclined at Levi's house as the honoree of a banquet-meal, he reenforced specifically why he had come into this world. We read in Luke 5:

Please don't, as some have, spiritualize what Jesus said, twisting his words to somehow mean “everyone is a sinner, some just don't realize it.” Heavens no. While I agree “the righteous” are sinners here in this text and agree that we all fall short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23), Jesus was being very specific: “tax collectors,” those Jewish traitors working for the Romans and “sinners,” those uneducated and ignorant of the law of Moses–this are the ones here that matter. The “righteous” here would have been understood as those educated and the temple-religious elite who despised “sinners” as unclean and impure. So, here we have Jesus being specific. You see how this works. Even Jesus did it. If hashtags had existed in those days, Jesus would not have said #AllLivesMatter, but #TaxCollectorsandSinnersLivesMatter.

At this point, I am more comfortable being specific for the concept “Lives Matter.” For those fighting the good fight against abortion, as an example, this should be a no-brainer, for we understand “All Unborn Lives in the Womb Matter.” You see how that works? Thus, I am for #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackWomenLivesMatter and #Under-resourcedLivesMatter and #MyNeighborMatters (see what I did there?). The problem is with “Lives,” not with the “All” that comes before it. And, that is why we need specifics “Lives” after the “All” because it actually matters. *See previous blog post, The church is God's space to make change: #Wives/WomenLivesMatter, #ChildrenLivesMatter, and #SlavesLivesMatter.

Platform for change: Output and Outcome Church Growth TrajectoriesDespite the musings of some that the NT church (and the early Jesus movement) was a protest against an oppressive Empire, the apostolic and early church lacked the power and a public platform for social and cultural change. However, the household temple-church filled in Spirit was and is the platform for making known God’s cosmic reconciliation through which cultural and social change was and is inaugurated in the world, particularly the worlds of our neighborhoods and communities. Christians did not “take to the streets,” but made known God’s cosmic reconciliation in the midst of household temple-churches through the reoriented relationships of reciprocity. Paul was calling, in particular, Gentile Christian men (i.e., the husbands-fathers-masters) to act against their own self-interests and against the norms of the dominant culture, literally to take up arms against the Empire by adopting the reconciled, sacrificial love of Messiah Jesus, demonstrating reciprocity to wives, children, and slaves. They must now live “no longer as the Gentiles walk” (4:17). Paul does not seek to overthrow the authority structures of the culture in which the Ephesian church found itself. But what he does do is instruct those in the family of God, within the all-welcoming worshipping venue, a new way of relating to one another in Messiah. This should affect what we consider as church growth. Buildings and addressed spaces do not foster relationships and authorities in a vacuum. In fact, a building decodes the concept of “the church.” This is true of a building-centered church experience, for our “church” experience and how we read and understand the Bible exist within a complex web of social, cultural, and religious meanings, habits, and relationships that are manifested in the fabric of our sacred spaces. In other words, a building-centered church experience fosters certain types of relationships, affirms a different set of authorities, and establishes a different set of burecratic powers than does a household venue as church. Today, church buildings tend to gather together the like-minded and those politically and economically similar—causing our building-centered sacred space and religious habits to be formed separate from other lesser individuals. Additionally, within a building-centered church experience the “power” a building has over people cannot be avoided, namely “the power of management, of expertise, or pure power against pure power,” while at the same time, ironically expressing “the power-refusing cross of Christ.” Perhaps, the reading of the command to be filled (Eph 5:18c) and the reoriented household code (5:22–6:9) offered throughout this paper opens other potential reasons for Paul’s final section—directly after the table—on the church, Messiah, and the powers. One could argue the need for sacred space identity in a place, but such arguments are deeply cultural. Paul locates the identity of the church both “in the heavenly places” (Eph 1:20–23; 2:6; 3:10) with the enthroned Messiah Jesus and “on earth” locally in household temple-churches. Yet, it is within the household temple-church(es) that God calls those in power, not to force others to submit, but for themselves to obey him through submission to others in the reciprocity of human relationships. As Dudrey insightfully points out, God “calls us not to seek empowerment, but to live out our lives in the moral and spiritual equivalent of martyrdom.” More specifically, God calls those with power into this new life of “martyrdom.” Within and through the household temple-churches that were spreading throughout the Empire, what it was to be human had been “irrevocably altered.” Albeit vast numbers of people flowed into the church—and that is certainly church growth as well—yet the filling in Spirit command and the reoriented household code provoke us to imagine church growth in terms of reconciliation among people, namely to recognize the value intrinsic to others and act in ways that promote outcomes of personhood (i.e., intentional reciprocity). As Megan Shannon Defranza has so poignantly observed in her book, Sex Difference in Christian Theology: Male, Female, and Intersex in the Image of God, “Postmodern vigilance on behalf of others and the Christian command to love our neighbors as ourselves call us to more careful attention to persons as they are found in the real world rather than in the ideal world of philosophical and theological systems.” Paul’s description of the household temple-church places real people from all strata of life together as church, literally giving priority of place to lesser persons and, more strikingly, calling those in power to show reciprocity in their associations with others. Therefore, potential church growth should also include outcomes of personhood and appropriate outputs (i.e., “church” activities) that ensure such outcomes. *For those following my thoughts on "Church Growth" here is my conclusion to the paper (and hopeful chapter in a forthcoming book) as I prepare for the upcoming November 2015 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta.

Other Not by the Numbers posts >> Intentional outputs promoting social mapping affirming mutuality and equality among persons10/31/2015 Introduction to the last section: A Temple-Church Architecture Reorienting Trajectory: Personhood OutcomesWith a contextually wider view of the Ephesians Letter, one of the outcomes of God’s cosmic reconciliation through Messiah can be seen in the transformation of the principal Roman social unit into relationships of reciprocity [see Russ Dudrey, “‘Submit Yourself to One Another’," RestQ, v 41/1]. This is even more substantial when we consider that the household code setting is framed within a temple-church venue, God’s new sacred place where believers gathered as the locally enfleshed fullness of Messiah’s body (cf. 1:22-23). Our observations of the code and its literary connection to the Spirit-filled temple-church (see Eph 2:19-22; 5:18) provoke us to reimagine potential relevant outcomes for the significance of how Paul works the household code text (5:22-6:9). The priority of the “lesser” household member (i.e., wives, children, slaves) in each pairing and the leveling of the male head of household through the expected reciprocity to the “lesser” members suggest that personhood (or the recognition of personhood) is an appropriate contextual outcome for the command to be filled in Spirit (5:18c). God’s new humanity (2:15c) is a result (an outcome) of his cosmic reconciliation (his output). Thus, the growing household temple-church in Spirit (2:19-22; 5:18-6:9) is God’s recreated sacred space where (a local) church growth is measured by local “church” habits and intentional outputs that promote a socially constructed reality wherein social mapping affirms mutuality and equality among persons (outcomes). *For those following my thoughts on "Church Growth" here are some concluding thoughts as I prepare for the upcoming November 2015 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta.

Other Not by the Numbers posts >> The fullness/filling, the Spirit, and the Ephesians temple-church. Andreas J. Köstenberger points out that “God’s subjection of all things under one head—that is, Christ (Eph 1:10)—sets the remainder of the epistle in proper perspective.” Paul, it should be noticed, takes up considerable space in the Letter linking the concept of filling/fullness, the church, and the Spirit throughout the Ephesians text. The Ephesians 5 filling command, then, is associated with God’s summing up of all things under Messiah, which links the filling to God’s cosmic reconciliation (Eph 1:10; 1:23; 2:16; 4:4, 12, 16; 5:23, 28, 30; cf. Rom 12:4-5; 1 Cor 12; Col 1:18; 3:15). The range of Ephesian referents associated with the work of God through the Messiah (the Head) and his church (Messiah’s body) to the cosmic reconciliation of his Lordship over alienated earth and heaven suggests that the Ephesians 5 filling command is to move us to reimagine the redemptive reordering of human existence. This suggests the same for the household code that syntactically follows (5:22-6:9) the filling command (5:18). As the temple-church is a reordering of human relationships (i.e., believing Jews and Gentiles together in one household-church, Eph 2:11-22), so also the household code is a reordering of the status quo and points us toward the concept of personhood as reflected in the relationship-trio. In chapters 1-3, Paul stacks up relevant terms (Messiah, body, filling, fullness, Spirit, head, subjection) to ensure the hearer/readers a vivid imagination of the church’s relationship to God’s redemptive/reconciliation action through the Son (the Head). In Eph 5:18 the concept of filling is also linked to the Spirit, drawing our attention back to Paul’s description of the Ephesians 2 growing/expanding temple-church (vv. 19-21), which is being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit (v. 22). The Ephesians 5 household code (5:22-6:9) even has a conceptual link to the Ephesians 2 temple-church in Paul’s reference to the Ephesus church as God’s household (v. 19c), where God is the paterfamilias. There are sufficient antecedent lexical and conceptual marks in the Ephesians 2 growing temple-church to indicate an epistolary connection to the Ephesians 5:18 command to be filled in Spirit and the following household (5:22-6:9). The sphere of the Spirit in Ephesians ought to influence the interpretive imagination of the Ephesians 5 filling command. The believers in Ephesus are sealed in Him with the Holy Spirit of promise (Eph 1:13) and they are not to grieve the Holy Spirit by whom they were sealed for the day of redemption (4:30; cf. Isa 63:10-11), connecting the Ephesians 5 filling to the Old Testament. The Spirit is related to temple images: the community of believers of Jews and Gentiles together (i.e., the one new man, Eph 2:15c), have access in one Spirit [en heni pneumati] to the Father (2:18) and are now, together, growing into a holy temple in the Lord (2:21b), which is being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit [en pneumati] (Eph 2:22). The connection is strengthen by the Ephesians 2 temple-church and the Ephesians 5 filling by en pneumatic (in the sphere of the Spirit) used in both texts. Finally, the sphere of the Spirit (en pneumati, Eph 6:18) is associated with prayer and petitions, also a temple related activity.The Ephesians 5 filling command, in light of its antecedent range of referents in the Letter, suggests that the command to be filled in Spirit is to be considered corporate, that is applicable to the saints who at Ephesus (1:1), as a (multi)household-centered church experience, rather than a command directed at the individual. Thus, it is better to understand the filling command more related to ecclesiology rather than anthropology, that an activity related to the temple-church (Eph 2:19-22). *For those following my thoughts on "Church Growth" as I prepare a paper for the upcoming November 2015 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta. Other Not by the Numbers posts >>

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed