Some sermon prep thoughts . . . the fuller text is Galatians 3:23-4:7 . . . and yes, this is a Christmas Season Sermon text . . . See Galatians 4:4. The part I am reflecting on is the well known Galatians 3:27-39: “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ's, then you are Abraham's offspring, heirs according to promise” (Galatians 3:27-29). I am not sure that we fathom how radically deconstructing these words would have been for the Greek, Roman, and Jewish man, especially male head of households, who were also masters of household slaves . . . nor can we (but we should) grasp the radical reconstruction and liberation these same exact words would have been to the Greek, Roman, and Jewish women and slaves and free (emancipated) slaves, who had no home or legal status whatsoever . . . interestingly we forget that Paul just mentioned sonship (“you are all sons of God, through faith,” v. 26) and will soon talk again about sonship and heirs (Gal 4:1-7), that is, being sons of God. I know we like to be modern and relevant and say “sons and daughters of God,” attempting to get past the so-called ancient gender-bias; but this is both unwarranted and does injustice to the text in its culture—depriving the Christian, especially the female Christian, of its impact. “Sons” were everything in the Greek, Roman, and Jewish world. They got everything. They had far more respect. They got citizenship. And if you were the first born male, an heir to family wealth, possessions, land, and legacy. The goal of marriage to the Greek and Roman was to produce a legitimate male heir citizen for the Empire. So, to deprive the female Christian direct title “son” with all of its rights and privileges (as it would have meant to the ancient world reader) would simply be not right, unfair, unjust, unbiblical . . . it would not be Christian. The impact of such sonship on the Jew, the Greek, slave or emancipated slave is left with no contemporary translative spin—as it should be. Yet, our cultural sensitivity (although sincere and well-meaning at times) toward the gender-bias we have robed the sister in Christ of the applicable impact on her status as a “son of God.” And, for sure, this simple slight of hand turning “sons” into “sons and daughters” makes us (you know I mean, us brothers) feel as if we’ve (they’ve) solved all the gender-bias (male-dominating, male-centrism) within Christianity and its religious systems, habits, and attitudes with one easy “translation” fix. In some since, this translative adaption helps to lessen the power of this text to deconstruct our male-centeredness and robs the church from allowing the place of the female to be reconstructed into the place of a “son of God.” It is no wonder the early church grew as it did . . . and it is no wonder why women were especially attracted to the fulness of time when God sent his son, “born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Gal 4:4).

0 Comments

Typically, church growth outcomes are limited to numbers of people indicated by an increased averaged attendance at one specific type of event (i.e., a weekly worship service) in one room (i.e., the “sanctuary” or space where a weekly worship service is held) at a particular addressed-place or tallied as increased paper membership at an annual congregational meeting. This is a building-centered form of church growth, which is foreign to the concept of “church” in the New Testament. On the other hand, Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians imagines believers “growing into a holy temple in the Lord” that forms “a dwelling of God in the Spirit” (2:21–22). The habits and experience of most who attend a building-centered church seem to focus on the individual Christian: sermons target those in the pew with generalized easy-to-make individualized application; the style and design of the service focuses on an audience of one to ensure faithful attendance; and, programs and activities are developed to meet personal needs. Furthermore, most building-centered churches are neighborhood-less, disconnected from the built space of the addressed-church building. By design or default, the building-centered experience is designed to move people away from their respective neighborhoods in order to develop and isolate the building-centered church community—again, separated from its built environment; programs and activities are designed to keep people returning to the “building.” However on the other hand, Paul’s reference to “the inner man” (Eph 3:16c) and the very temple background reverberating throughout Ephesians, as well as, the immediate context (i.e., Eph 3:1–13, 14–19, also 20–21) focuses us, the reader/hearer, on the importance of rethinking “church” and helps to establish a biblical understanding of church as sacred space. This essay seeks to establish Paul’s “inner man” (3:16c) as a corporate temple reference (befitting the context) and as an allusion to back to the Ephesians 2:15c “one new man,” that is God’s growing church-temple. This essay offers a corporate reading of Paul’s Ephesian 3:16 “inner man” reference, which reinforces the gathered-temple-church, the one new man, as sacred space, the liminal space space between (the heavenlies and a local neighborhood, let's say); and, as such, the local temple-church has revelatory significance for disclosing the wisdom and mysteries of God (cf. 3:8–10). This implies that church growth outcomes go (far) beyond mere numbers of people and may include, as the antecedent one new man suggests, social, demographic, and justice outcomes as well. The ensuing study will develop this thesis (I) through leveraging the concept of sacred space as a socio-rhetorical interpretive-model; (II) by weighing the context to determine a “corporate” or “individual” reading of Paul’s use of “inner man” in Ephesians 3:16; (III) by showing that Solomon’s temple dedication and other Old Testament temple texts have implications for a corporate reading of Paul’s “inner man” reference; (IV) by summarizing how a corporate reading “inner man” that denotes the revelatory nature of the temple-church; and, (V) by presenting a list of inferred outcome relevant to church growth.

I am reading an article called “The Nothingness of the Church Under the Cross: Mission without Colonialism” by Ry O. Siggelkow. Two things strike me right away in reading this article, especially since I have been thinking about this myself in recent years: First, the author says what is at stake is the very question of the truth of the gospel itself and the extent to which the presence of Christian mission and western colonialism marks nothing less than a denial of the gospel. Furthermore, any theological study, it seems, needs to also understand the theological conditions by which the gospel itself became “bound theologically, ideologically, and practically to established powers” (e.g., institutions, the state, educational processes, business success, and of course affluent and status-ed people—my list of “powers” not Siggelkow's; he doesn’t id the powers except for the implications of the word “colonialism”). The author writes that the question, then, of mission, today, is what is mission now in a post Christendom context. I would say, rather, now it is understanding mission, not so much in a post-Christendom context, but rather in a context in which the church and its institutions are seeking to only partially free itself from only parts of Christendom. Second, in the long stretch of history we have seen the diminishing of what is evident in the NT, namely the parousia. Some call this the second coming of Jesus. I will call it the “apocalyptic expectancy and hope” (as does the author) of the imminent coming of Jesus. This expectancy and hope is solely lacking and, in some minds, has for all practically purposes vanished. So, we have exchanged the expectant hope of Jesus’ second appearing in the fulness of his kingdom with political visions (right and left, we all do this, even the woke). The “slacking of apocalyptic expectancy and hope” has made church leadership, and as a result, the church—at least in the western American church—dependent on the systems and structures of Christendom. Those that rant against Christendom, however, are selective, nonetheless, as to which parts of Christendom (i.e., to which aspects of its systems and structures and institutions) are ranted against and those that are passively accepted and/or embraced. This is to some, a matter of survival, especially for those invested in such Christendom systems and institutions. Yet, as far as I can tell, the NT doesn’t teach us to do what it takes so the church survives; the NT teaches us to be church and expect the Lord Jesus to return–and to act, suffer, and endure accordingly. An apocalyptic gospel is always destabilizing, both for the institutional church (local or otherwise) and, as well, society (for which many/most Christians form their identity, seek stability, and pump up their status). No wonder a threat to Christendom is a threat to much of the church (and its institutions) and to us, our social and cultural us. In part, this is what made the world-turn-up-side-down at the birth of the church, at least until Constantine aligned the state and the church together. (Presto, Christendom was born!). Some thoughts to make us rethink church. *This post incorporates some of the words and phrases used by the author of the article and deserves a thread of footnotes. But the thoughts and conclusions are mine, of which I take responsibility for.

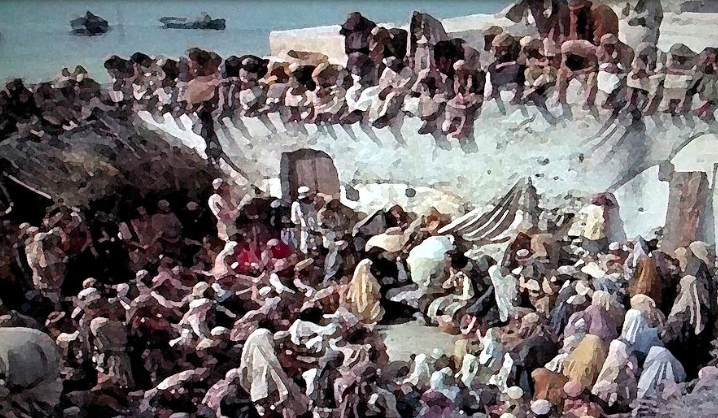

Recently during a Sunday sermon on Matthew 11, I asked: “How do you think the young church, with nothing much to offer, no social or political power, possessing little resources—and life didn’t really get easier and better for early believers. They risked everything, and for most, life got harder. How do you think, in the first 150 years after Pentecost, Christianity became the largest religious sect in and around the Empire? How? “They changed their households . . . street by street, village by village, at the table [I pointed to our table where we would shortly celebrate the Lord’s Supper together]. It all changed right here where gathered-churches lived out ‘Come all who labor and are heavy laden.’ “The body of Christ, the local church, with Jesus our Head, ruling and reigning at the Father’s right hand, is His presence in its community. We show them Jesus by who we are and what we do so that all who struggle and toil and are carrying burdens no one should carry alone hear (because they see) the invitation to Come to Jesus and take on His yoke and find rest. We are to embody the invitation to Come.” ¿Como piensas que la iglesia naciente sin nada que ofrecer, sin poder, careciendo de recursos? - y la situación no se puso ni mas fácil ni mejor para estos primeros creyentes que se arriesgaron todo, sino la vida mayormente se les hizo aún más difícil - ¿Como piensas que dentro de 150 años el cristianismo llegó a ser la religión más prominente en y alrededor del imperio Romano?

¿Cómo? Ellos hicieron cambiar sus hogares ... calle por calle, aldea por aldea, en la mesa. Todo se cambió allí mero, donde las iglesia reunida practicaba el "Venid a mí, todos los que estáis cansados y cargados." El cuerpo de Cristo es la iglesia local, con Jesús como nuestra cabeza regiendo y reinando a la diestra del Padre, su presencia en esa comunidad. Les demostramos a Jesús por quienes somos y por lo que hacemos para que todo aquel que lucha y labora y que lleva carga pesada no lo haga a solas porque oye y ve la invitación de venir a Jesús y tomar su yugo y hallar descanso. Debemos encarnar la invitación a venir.

And this is why church, that is ecclesiology, is so so important.

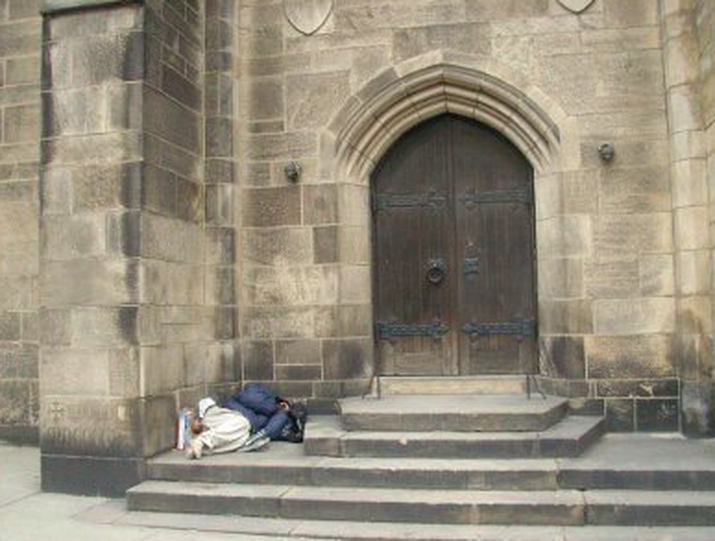

I have been wrong on many things theological over the years (e.g., nature of man and nature of sin, God's sovereignty and election, the importance of the Lord's supper, and too many more to be embarrassed over, which I hope I know better now), but the biggest “didn’t get” was “church.” I, like most of us, define “church” by and through our culture, our sociological history (i.e., our story), even my personal story, and my social location as (now don’t get offended, or maybe you should)—my social location as a white, suburbanite, living in America, and a person within a westward marching, European cultural history (story). Really need to rethink church and do so within the context of the biblical story.  Just saw a rather good tag line in a meme: "Is there room for me in your Christmas?" Yes, I know a cliché, but this time there is valid application. I sure like this Christianese cliché more than the other-ad nausea-one: Jesus is the reason for the season--and here's why: Of course the original Christmas story teaches us somethings about the Christ, the second person of the trinity, the Son of God become flesh (very very important stuff), but these texts are to help us understand the nature of redemption--the gospel--and the purpose of the church. So who we are as church is to be lifted from this story. So, here goes: "We are the reason for the season." Not only did Jesus come to save us (i.e., the reason for the season), but we are Christmas to the dying world. And, I am wondering if all our attempting to follow the retail and commercial world in our presentation of the Christmas story has taken us away from our role in all the gospel. As for the other meme quote, "Is there room for me in your Christmas?" is so relevant a question for the church, the local church. There are so many people (do I really need to list them for you?) that are wondering about just this with regards to our churches. What, really, whom don't we have room for "at church"? Not only has retail highjacked Christmas, in some way the church has as well made retail our bottom-line; making it exactly the same as retail version to grow our churches, up-contributions, and make us feel all warm for this holiday season. Here's the rub: What does our way of "doing church" (and doing Christmas) suggest or teach others for whom we do and do not have room? Think more deeply about Christmas this year.  I read books that challenge me, push my convictions, and expose my idolatries. No book, recently, has done this as has Christine Pohl’s Making Room: Recovering Hospitality as a Christian Tradition as I digested page after page. As many who have the patience to read my posts and blogs, I have been rethinking church and its relationship to the poor for some time now. It’s has gotten somewhat more personal as I have been challenged to reevaluate the concept of Christian “hospitality.” Pohl reminds me that biblical hospitality isn’t entertaining friends and family, but the household extending relationships and meeting the needs of the poor and marginal, nearby and traveling through. Typically, most in the church seem to understand hospitality (or the “gift” of hospitality) to be the entertaining or hosting of those we already have some form of relationship (“established bonds”) or shared social status and “significance common ground.” Here, “[h]ospitality builds and reinforces relationships among family, friends, and acquaintances” (13). This kind of hospitality reinforces the shared social status among host and guests, wherein the guests give or affirm something by their presence to the host. Frankly put, this “kind” of hospitality is simply entertaining of guests who affirm or build the host’s social or ecclesiastical status. This is not biblical hospitality. There is commonality, that is the liminal space is shared by hosts and guests before, during, and after the act of hospitality. However, biblical hospitality is more closely related to offering space, comfort, and resources to the stranger, the poor, the marginalized—someone outside or estranged from one’s social status, whereby nothing is gained or affirmed by the hosts. This kind of hospitality, framed by the nature of the gospel itself, is for those disconnected from basic relationships and resources. As Pohl reminds, this “hospitality is central to the meaning of the gospel” (8). Thus, in a real sense,“[h]ospitality is the lens through which we can read and understand much of the gospel, and a practice by which we can welcome Jesus himself” (8). The act of hospitality is a concrete display of the gospel. Prior to hospitality, the host and guests might very well be living out a world that affirms verticality; yet the household becomes a gospel-liminal space that affirms horizontality. This reality—where the gospel is displayed, that is where a leveling of human relationships takes place amid the basic human entity, the household—is an expression of God’s kingdom. Granted biblical hospitality isn’t a mere “how to” for the Christian faith nor should be considered lightly. Yet, I cannot rethink church without considering the Christian tradition of biblical hospitality. It is stretching, convicting, and stressing me to think more deeply. Here is a series of quotes from Making Room that confront me on the issue of being Christian, having resources amid the scarcity of many, and the concept and practice of hospitality. “These hospitality communities embody a decidedly different set of values; their view of possessions and attitudes toward position and work differ from those of the larger culture. They explicitly distance themselves from contemporary emphases on efficiency, measurable results, and bureaucratic organization. Their lives together are intentionally less individualistic, materialistic, and task-driven than most in our society. In allying themselves with needy strangers, they come face-to-face with the limits of a ‘problem-solving’ or a ‘success’ orientation. In situations of severe disability, terminal illness, or overwhelming need, the problem cannot necessarily be ‘solved.’ But practitioners understand the crucial ministry of presence: it may not fix a problem but it solves relationships which open up a new kind of healing and hope” (112). “Recognizing our status as aliens in the world is important for attitudes toward resources and property. Although for most of church history private property was taken for granted, its use among Christians was sometimes moderated by the teaching that everything beyond necessity belonged to the poor. Most of the normative discussions of hospitality assumed that God had loaned property and resources to hosts so they could pass them on to those in need” (114). “In the second-century writing of Hermas we can see an important connection between alien residence and the use of resources. The Similitudes began with the claim that servants of God are living in a ‘strange country,’ far from their true home of heaven. Given their alien status, it makes little sense for believers to collect possessions, fields, or dwellings. Christians live under another law; whatever they have beyond what is sufficient for their needs is for widows, orphans, and other afflicted persons. God gives more than sufficiency for that purpose, not for making believers comfortable and vulnerable to the enticements of a strange land (Sim. 1:1–11)” (115). “If Christians live ‘in a strange land as though in [their] home country,’ they build ‘extraveagent mansions,’ and indulge in ‘countless other luxuries,’ wasting their substance on ‘inanities’ [a nonsensical action, silliness]. Because, when forced to leave the land of their sojourn they will be unable to take their possessions and buildings with them, Christians should instead use their wealth to benefit those in need” (115). Seems that much of our "church" experience affirms our cultural's values regarding social status, continues the horizontal nature of social status quo, and displays the divisions fostered already in society. The way we do church isn't neutral to the issues of poverty, racism, and wealth. Biblical Christian hospitality reverses all of this and helps us to question what we truly believe as Christians concerning our "landed" status as aliens of a different kingdom.

Each spring I attempt to write a brief paper for our Northeast Regional Evangelical Theological Society. This year (2016) I thought I’d put together a study on the Synoptic writers’ use of “crowd” (oxlos) in their Gospel narratives. Below is my paper submission abstract and outline, along with a brief reflection on how I came to consider “crowd” as a Gospel character. A Real Time, Messy Missional (Local) Church: What “Crowd” as a Gospel Character Teaches About Being Missional-Church Pastors and lay-teachers tend to be more comfortable focusing on cognitive effects and propositional aspects of the gospels like Jesus’ preaching, parables, and teaching. Characters are another matter in the gospel narratives, for they are more likely to be “identified with” or used as “lessons” in which they tend to be allegorized, devotionalize, or typified rather than seeking how they are used in the story and, thus, developed for their contextual interpretive significance. The “crowd,” on the other hand, is rarely viewed as a character in the Synoptic Gospels and, thus, often not considered for its interpretive value. The “crowd” character presents a difficulty for the interpreter of the Gospel narratives. The “crowd” is that messy, unclear presence at much of Jesus’ ministry—sometimes for Jesus, sometimes against him, occasionally believing, oftentimes unbelieving, and, then, more so, it is split believing and not believing. And what makes the interpretation-application process even more troublesome, often the reader is left just not knowing the crowd’s confessional state of mind. One thing is consistent, however, the “crowd” is almost always present at Jesus’ public activities, teaching, and travels. Conversely, one could posit that Jesus was present among the crowd in much of the Synoptic Gospel narrative. Assuming that the Gospels were written to help local, believing communities to imagine how the gospel was to inform and form their discipleship and missional purpose, the “crowd” has value at the teaching level. What does the Synoptic Gospel crowd reveal about a church’s mission and presence among others? Is our building-centered church experience prohibitive of such crowds? What can the significance of the Synoptic Gospel crowd (as) character tell or instruct us on how we should do church, today? To give this a contemporary social location, the forming significance of “crowd” as a Synoptic Gospel character should be juxtaposed with the forming power of a building-centered church experience and how this affects the missional life of the local church. We should grasp how a building-centered church experience is anti-crowd; the “crowd” as a Gospel character should inform our exegetical-significance-application process; we should observe how the role of “crowd” and its impact in the text informs the missional purpose of a local church; and, the significance of “crowd” shows is what is suitable “space” for a local church. This effort here [in the full paper] seeks to demonstrate (conclude) that a missional-church creates space for crowd to engage the gospel of the kingdom. A preliminary reflection on “crowd  After studying and writing on the Mark 3 Beelzebul passage and “the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit” (it isn’t what you think it is; trust me), I was fascinated by Mark’s use of “crowd” throughout his Gospel. If we take Mark as inspired and his use of “crowd” as a strategic character in the gospel story, it seems to me, we should grasp the crowd’s significance within our understanding of both the gospel and, as well, the (local) church. Obviously more needs to be studied and written on this, but a brief forethought on crowd is worth it as we strive to rethink church. One specific characteristic of the “crowd” worth noting, it is always around Jesus (or Jesus is in the midst of the crowd), meeting and greeting him, listening to him, and sometimes literally jumping over one another to be near to what Jesus was doing or saying. Second, another aspect to grasp, the “crowd” is sometimes believing and sometimes unbelieving, and sometimes, well, you just can’t tell one way or another. Sometimes the “crowd” is even split by belief and unbelief. Yet, the presence of Jesus was marked by the presence of "crowd" (ochlos).  I have come to the conclusion this is the way it should be with the (local) church, which is God’s fullness, Christ’s body local (e.g., Ephesians 1:22). Seriously, as the body of Jesus, the church, that is, a local church, should be surrounded by “crowd” in a similar fashion as Jesus himself was surrounded by “crowd.” We read out such inferences (to “crowd”) in the Gospels and mostly cannot conceive the church’s role in this way. This is one of the negative aspects of our building-centered church habits. We need to stop thinking church as a building, and acting like it is—in fact, a building-centered church experience is prohibitive of this crowd-missional aspect of the church's purpose and, can be, antithetical of gospel. We, as evangelicals, are uncomfortable with crowds “at” church; uncomfortable where the categories of believing and unbelieving are rather foggy. (This does havoc on a high fencing view of communion, for sure.) This suggests we need to rethink church and where “church” (and possibly how it) happens. Whereas the inner circle of followers and disciples (we more comfortably refer to as the church members or regulars attenders) are believing (and sometimes maybe even struggling to believe) and, at differing levels, learning obedience, on the other hand, the outer circle that surrounds the church (and sometimes crowding inside as it were) is a little foggy on the issue of belief. But, they ought to be there—sometimes they’ll look like believers, sometimes they won’t, and sometimes you just will not be able to tell one way or another. We need to see “crowd” around the (local) church as a vital character in the (local) church’s story within the community it seeks to minister and serve. Perhaps more biblically accurate, we should experience church in the midst of “crowd,” for the church is Jesus’ body--and this is what Jesus displayed in the Gospel narratives.  I am in favor of and an advocate for a public social service net--I worked hard at and made my livelihood from one for many years. I have designed and facilitated many programs on behalf of our most vulnerable. While still a good thing, I am very weary of a government-run and semi-government (by design which receive substations government funds either by the grant process of by legislation (or law) non-profit system (yes, they are one system) whose programs still leave the poor in poverty with little or no escape (no upward mobility, if you will) and, in the end, that mostly benefits the politicians and EDs/CEOs who are dependent on the poor, well, being poor for their votes and grant money, and, as well, the massive bureaucracies--the armies of clerical and professional poverty-fighters whose livelihoods and their own upward mobility are only secure in as much as poverty continues. The least likely beneficiary for such a system is the actual poor. In fact, too many people and groups are dependent on the poor remaining poor. I have a problem with this. It is time to rethink how poverty is addressed.  Even large corporations—the biggest ones—aren't geared to support a truly anti-poverty approach to, well, end poverty and/or move the poor out of poverty. Year ago now, I had asked one of the most involved funders of poverty programs (GE, Inc.) if they'd consider a new approach to fighting poverty, one that will actually move individuals and families OUT of INTERGENERATIONAL POVERTY and the response: "Sorry, we can't. That's just not one of our buckets." Yes, indeed, all players need to be at the table (including BIG BUSINESS and the GOVERNMENT), yet I believe the church, or better, churches (implying churches local) are the ones to offer a new (really an older) paradigm for fighting poverty. But, in order to be able to and best be positioned to alleviate poverty and actually move people (really communities) out of poverty, the church needs to rethink church, which in the end might be the harder system to undo.

When Jesus called his disciples to “follow me and I will make you become fishers of men” (Mark 1:17), most assume a positive evangelistic outcome of reaching people for Christ. Nothing could be further from the reality behind Jesus’ intentions in calling out followers to be such witnessing-fishers. At least the benign, banal application of making this verse a proof-text for “witnessing” is a shallow and narrow application of Jesus’ powerful imagery cast in this tremendous text.

Tax collectors are outsiders; rich they might have been, but they were in the eyes of temple leadership, traitors to God and to God’s people. Yet, the sinners are most certainly the uneducated serfs and peasants, farmers, and those who lived on the margins of life in and around Jesus’ house in Capernaum of Galilee (2:15). One cannot spin from this text a general characteristic that “sinners” are all sinners anywhere you find them. As are the "tax collectors," they are a specific demographic associated with those living as the poor and marginal of Jesus’ day. Jesus’ response, then, takes on an ominous shadow—a fisher shadow, standing on the shore, cast into the waters of those that are "healthy." True fisher-followers of Jesus will not rationalize their standing in the community nor their affluence, but will count their privilege, their advantage, at the disposal of the “sick” who need a physician. Paul is not far from the same imagery when he describes how Jesus took his advantage (his privilege) and gave it all on behalf of all those with the greatest of disadvantage. Have this attitude in yourselves which was also in Christ Jesus, who, although He existed in the form of God, did not regard equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men. Being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross (Phil 2:5-8). Most likely Amos 4:1-2 is one of the underpinning Old Testament referents that would have given the disciples a frame, a rather menacing edge, for understanding the potency of Jesus’ call on their lives. In view of the inclusion (contextually) of Amos 4:1, namely the “cows of Bashan” referent, I have become wary of the poorly distributed resources, talents, and wealth among the richer, more affluent churches at the expense of the poorer churches, neighborhoods, and urban mission fields. By “expense” I am thinking biblically, not culturally, socially or (heaven forbid) politically, nor through the lens of class, but by the very New Testament discipleship implications, namely that those with advantages (“privilege,” if I may) who are called by their association with Jesus to help those who are at a disadvantage. The assumption that it takes more money to reach the rich and affluent than the poor is turned on its head by the very presence of the Kingdom (cf. Mark 1:17 with Mark 1:14-15). A more gospel-centered and mature view of discipleship seem to argue that it takes far more resources to go into the poor urban fields to bring forth a harvest for the gospel of the kingdom. These are under-resourced communities in every imaginable aspect of life. As affluent Christians, we tend to justify our station in life as a combination of gift and hard work and hear any talk of “privilege” as a justification of those of lesser means, with poorer gifts, and perhaps, with what we perceive, a lesser work ethic to grab what we have for themselves. Is there no wonder the affluent in the days of both Amos and Jesus attempted to rid themselves of the troublemakers who upset the "healthy's" status quo? This will be the lot of fisher-follows of Jesus in any culture. Following Jesus, as the gospel is imagined by Mark (and the other Gospel writers), put us at odds with everything we hold dear, in particular those who have the advantage in resources are to empty themselves on behalf of those who are at a disadvantage (cf. Phil 2). The fisher-follower mission is toward the sick (of our society), not the healthy (in our society)—toward the disadvantaged and not the advantaged. Michael Card prophetically reflects this Marken view of Jesus and the gospel in the words of his song, The Stranger:

For a youtube of Michael Card's "The Stranger" >> Click here *See chapter 3, “‘You Will Appear as Fishers’ (Mark 1:17): Disciples as Agents of Judgment,” in my Wasted Evangelism for a further and more detailed study of the Mark 1:17 “fishers of men” passage.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed