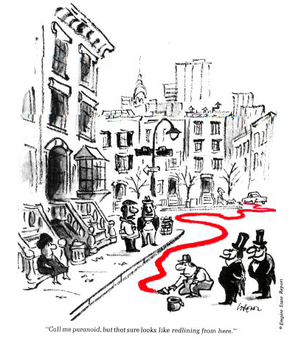

Conclusion: Social Action as Christian Apologetic  Simply, affluent suburbanites, despite a claim to a higher work ethic or a more developed sense of responsibility, didn’t do it on their own; they had help along the way. (I know, many do not like to hear this, but no less truthful.) On the one hand, the non-poor’s social construction of reality, which they now experience as everyday life, allows them to benefit, not just from the market, but also from past actions of government that laid much of the groundwork for continued prosperity. On the other hand, the concentration of poverty in central-cities is not simply about laziness, slothfulness, or even personal sin. (I assume the non-poor who benefit from the current structure and mediating institutions are just as much “sinners” as those living in geographic areas of concentrated poverty.) Indeed, much of what is in place and experienced now as normal arose from various forms of racism and redlining practices, as well as “the concentration of subsidized housing projects” that, as Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck observed in their Suburban Nation, “destabilized and isolated the poor, while federal home-loan programs, targeting new construction exclusively, encouraged the deterioration and abandonment of urban housing.” The fact of poverty and the reality of those affected by it in the central-cities could not have happened any more effectively if it were actually planned and implemented with malice. Without the aid of government policies and subsidies, as well as municipally empowered zoning laws and discriminatory business policies, the foundation for exurban wealth in America might not have happened. Rather than lamenting this inequitable state of affairs, participants, including many non-poor Christians, have been encouraged to rejoice in the “prudence” of such strategies and the institutions, capitalism and the “mythical” market, that sustain them. The modern, non-poor suburban dweller is the heir of such socially constructed forces.

Emil Brunner once remarked, “For every civilization, for every period of history, it is true to say, ‘show me what kind of gods you have, and I will tell you what kind of humanity you possess.’” For the Christian and Christian community it is: Show me what kind of association you have with those living with the effects of poverty, and I will tell you what kind of god you worship. The reality of everyday life is that Suburban life and its enablers—the free market and human acts of power—are often at odds with the gospel, especially a gospel that has been formed by the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition. For the non-poor Christian, this is an idolatrous mode of living and does not offer a biblically defensible apologetic for the God revealed in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 *adapted from chapter 5 of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism

0 Comments

I am reading or have read recently a number of books that seek to explain how we arrived at our very distinct demographic and mostly ethnic divisions that exist today—urban, suburban, and now exurban. (I will leave the rural landscape for others who have studied it more adequately.) Amid these books I am also learning how we have developed a functionally dependent class, mostly non-white, that live and try to survive in the most dense urban areas of our country. Much of what I have read affirms my own writing on the subject, which found its way into chapter 5—“Idolatry and Poverty: Social Action as Christian Apologetics”—of my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church’s Task of Evangelism. Below is a three-part adaption of the latter subsections of this chapter. Idolatry promotes a defective social reality for the non-poor Christian In his Nature and Destiny of Man, Reinhold Niebuhr observed that idolatry is making the contingent absolute, something relative into “the unconditional principle of meaning.” Luke Timothy Johnson points out that, when we consider something as ultimate, this is worship, not just what our lips or cultus ritual render, but in the exercise of our freedom in service to that which we consider absolute and unconditional, and, thus, derive our significance. It is, however, not just an image fashioned with gold and silver that provides the danger and potential of idolatry, for the Bible is clear, such man-fashion idols are no-things (Isa 41:21–24; 44:10; Ps 115; 135; Acts 14:15; 1 Cor 8:4; 10:19; Gal 4:8). Johnson reminds us that “important idolatries have always centered on those forces which have enough specious power to be truly counterfeit, and therefore truly be dangerous: sexuality (fertility), riches, and power (or glory).” It is the body of knowledge that accompanies the object and the habits of service in worshipping the objects (i.e., idols) and, then, the social and cultural habits that follow that develop an everyday “world,” with meaning and definitions for relationships (repeated action, mundane habits), that objectifies reality and maintains significance and plausibility (its symbols and corresponding institutions). Our socially constructed world, then, is reality formed by our service of worship and sustained (validated) through the habits and experience of everyday life.

However, to understand fully the non-poor’s everyday reality, it is simply “not enough to understand the particular symbols or interaction patterns of individual situations.” It is how the “overall structure or meaning” within “these particular patterns and symbols” are experienced. As we seek to apply the gospel that is embedded with texts regarding idolatry (e.g., the overwhelming number in Mark’s own gospel) and, as well, texts indicative of relationships toward the economically vulnerable, it is important to understand how the social-location experienced by many non-poor Christians was formed and its implications for their (i.e., the non-poor) participation in the outcomes of this social-location. Religion once offered an integrating principle that helped provide a “life-world” that was “more or less unified.” But, modern life not only provides a less unified everyday life, now religion often aligns itself with the socio-economic forces that help sustain the plausibility of our faith, which can then inoculate the non-poor Christian from the idolatrous forces embedded in their social-location. Over time new symbols and signs (lawns, yards, gated communities, commutes and highways, social status, shopping malls, upward mobility, the market, double-entry accounting, etc.) that permeate the social-location the modern non-poor Christian experiences as everyday life compete with biblical symbols (e.g., the words of God, the cross, redemptive-historical acts of God in history, etc.). Johnson reminds us, “Prior to any action or pattern of actions we might term ‘Christian’ is a whole set of perceptions and attitudes, which themselves emerge from a coherent system of symbols, and an orientation toward the world and other humans, which we call Faith.” In fact, the very habit of experiencing the fragmented, often unintegrated social-locations over and over everyday might feel like freedom bestowed by our socio-economic system, but actually weakens the plausibility of biblical faith to inform our home world. Non-poor Christians are in danger of idolatry when finding themselves in need of affirming “this worldly” system and its institutions as God-given in order to be at home, plotting their lives on the societal map provided by social institutions rather than biblical discipleship in order to relate—comfortably, plausibly, securely—to the overall web of acceptable meanings in society. As Berger in Homeless Mind points out, because of the plurality of social worlds—work, school, play, third places, highways, commutes, home, shopping, church—in modern society “the structures of each particular world are experienced as relatively unstable and unreliable.” The separated sectors of our social world are rationalized and relativized, forcing the non-poor Christian to justify religiously this worldly system and institutions in order to feel less exposed and vulnerable and more relevant and secure. After decades of political alignment and religious justification, for the most part, the non-poor Christians living in the suburbs now feel at home.

Idolatry and Poverty: “idolatry comes naturally to us" (samples from a chapter in Wasted Evangelism)6/25/2017  Christian responses to poverty often draw from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5–7; Luke 6), further substantiated by other NT teaching (e.g., Acts 2–4; Jas 1–2). Although important, this tends to be applied more to church-life and to the private sphere rather than developing a response to those living with the effects of poverty. Others turn to the Pentateuch and the Prophets, and, rightly so, for such biblical material is rich in addressing the issues of poverty. The results, however, can tend toward justification for political alignment and socio-economic policies (right/left, conservative/liberal). Christians across the spectrum wrestle with how the Pentateuch and the prophets apply in the (post)modern world. Many question the contemporary relevance of such documents of antiquity addressed to an ancient nation whose social-political location is the Ancient Near East. Nonetheless, there is a way to decipher the significance of OT ethical texts, namely to draw significance from their incorporation into the gospel itself. Mark draws upon a fascinating range of OT contexts throughout his narrative that juxtapose idolatry and the economically vulnerable. Although Mark’s use of the OT is extensive beyond these particular texts, he embeds his Gospel with OT contexts related to the economically vulnerable, whether Law, land-stipulation, or prophetic announcement, which also contain, within the context or flow of thought, mention of idolatry.  The juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty in Exodus and the memory-judgment context in Malachi bear out the apologetic framework discussed above. Additionally, Mark’s constant use of Isaiah also reinforces this framework, which is particularly vivid in Isaiah 40, a component of Mark’s programmatic summary. Mark’s Isaiah referent itself--A voice is calling, “Clear the way for the Lord in the wilderness; make smooth in the desert a highway for our God” (Isa 40:3; Mark 1:3)—carries imagery common to Isaiah’s world, reflecting the procession of ANE monarchs. Here, Yahweh comes as Victor-king, announcing the Good News (v. 9), where all flesh will see the glory of the Lord (v. 5). Isaiah 40 then compares Yahweh to surrounding idolatrous nations, which are like a drop from a bucket (v. 15) and are as nothing before Him . . . less than nothing and meaningless (v. 17; note v. 23). Mark’s introduction contrasts the gospel to the concept of the imperial cult of Caesar linking it with the apologetic of Isaiah, emphasizing the incomparability of Yahweh, whose sovereign power over creation is boasted of (v. 12) and affirmed to be in need of no-one’s counsel regarding justice (vv. 13–14). Yahweh is distinct from the image-bearers made of gold and silver who need to be fashioned by human-hands (vv. 19–20), for he sits above the circle of the earth and stretches out the heavens like a curtain (v. 22). The Holy One takes on all-comers: To whom then will you liken Me that I would be his equal? (v. 25). Isaiah notes the starry hosts (v. 26), each representing idolatrous pagan powers, yet it is Yahweh who created them and calls them by name, indicating his might and strength over the idols of the nations.  Mark’s consistent references to OT material that juxtaposes idolatry and the poor is certainly embedded into the very nature of the gospel, suggesting that the gospel is formative for social arrangements. Mark’s highlighting of these OT texts that juxtapose idolatry and expectations regarding the poor, as well, points to an apologetic and evangelistic potential for social action. Still, moving from ancient text to significance to application can be very difficult, especially as we consider how the application of such texts can include social action outcomes. At the risk of over-generalization, even Christian approaches to poverty tend to align with political views, party affiliations, and social-locations: Politically conservative Christians tend to read capitalism, free markets, and individual charity as biblical solutions to poverty; the politically liberal tend to read more public, state-centered solutions. Although both find some textual support, neither consider the biblical juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty, nor our own human capacity for idolatrous alignments in our own social-locations. L. T. Johnson reminds us that “idolatry comes naturally to us, not only because of the societal symbols and structures we ingest from them, but also because it is the easiest way for our freedom to dispose itself.” Shifting the issue of poverty to the realm of discipleship and apologetics focuses our attention on the social-location of non-poor Christians and their relationship to the poor. In light of the gospel framed by Mark, non-poor Christians should be mindful of the idolatries that can form their own social reality, particularly those experiencing everyday life in places where poverty is not concentrated (i.e., non-urban life). It is not necessarily how OT ethical texts apply to our modern social-location (although important) that is significant, but how the apologetic nature of the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition relates to those who are to be formed by the gospel, then, how that significance dissuades Christians from conforming to any private vs. public dichotomous response to poverty.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed