A gathered-church: scandalous, not so family friendly to the status quo, yet their only hope3/24/2018  “Finally, all of you, have unity of mind, sympathy, brotherly love, a tender heart, and a humble mind. Do not repay evil for evil or reviling for reviling, but on the contrary, bless, for to this you were called, that you may obtain a blessing. For ‘Whoever desires to love life and see good days, let him keep his tongue from evil and his lips from speaking deceit; let him turn away from evil and do good; let him seek peace and pursue it. For the eyes of the Lord are on the righteous, and his ears are open to their prayer. But the face of the Lord is against those who do evil.’ Now who is there to harm you if you are zealous for what is good? But even if you should suffer for righteousness' sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled, but in your hearts honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame. For it is better to suffer for doing good, if that should be God's will, than for doing evil” (1 Peter 3:8-17). Church (or that big word, ecclesiology) finds its relational or social foundation in the terms and concepts of “household” and “family.” The church (really a locally addressed gathered-church) is a new kind of “household,” a new kind of “family”; with a new definition, not of blood, but from new birth in Christ, that is a company of gathered strangers and unequals who are now in Christ, where the Spirit of God dwells, and who are the presence of Christ (His body) in space and time in a community, a neighborhood, a spot on the map. The presence of this new family, a local gathered-church, was viewed as inappropriate to the social order of the Greco-Roman (even Jewish) world by those outside the church, especially by those in authority and those who had power over the social order; and, thus, was viewed as a threat to the status quo and social order. The church was dangerous to those who were in power (from Caesar to male head of households). The question is, do we, the local church, so look and feel like the world and social norms around us that we are no longer a real threat. We do not read well our text here in 1 Peter 3 (above) unless with get, unless we grasp the church as “as aliens, scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1) was a threat to the Roman Empire and its ordered way of life. This text reminds us of who we are as a gathered (local) church—in a neighborhood—that is, first, a safe space for a gathering of strangers and unequals, a new kind of family; and that, second, our gathering together as church and our putting on Jesus provokes those outside the church to ask us about the hope we have in Christ. On the one hand we ought to be scandalous, while at the same time be the hope those who are outside need.

0 Comments

III. Above all this scene reminds us as a gathered-church, we are wholly at odds with Caesar and all the powers—the tables are turned The final of the three Pilate-questions that occupy our attention comes after Pilate could find no guilt in Jesus, “Shall I crucify your King?” This question sets up the statement of all adamic statements: “We have no king but Caesar!” The Jewish leaders themselves had become frustrated with Pilate and, so, had turned to the clincher of their argument for doing away with this Jesus--they made it all about Caesar. They do what the world always does: they change the characters in the judgment hall. They put Pilate before Caesar rather than Jesus before Pilate. The Jews set Pilate up, for when “Pilate sought to release him” (19:12), the Jews cried out, “If you release this man, you are not Caesar’s friend. Everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar.” And in their last breath, the words that confront us all, Pilate was done—out-done: “We have no king but Caesar!” The ironic thing, the Jewish leaders didn’t want to defile themselves by going into Caesar’s Jerusalem judgment hall, yet they had carried Caesar in their hearts, leaving them most defiled and guilty at their very core before God. As he had tracked the Jewish leaders and Pilate down to that very moment, Jesus puts every listener of this story, us all, on trial. Who is your king? But I don’t want to leave this here before the individual—which of course each of you, each of us must decide who is our king? —but I think we need to go right to the listeners of this in its original setting and see how this all works for church, for a gathered-church. This scene parallels the apostolic and early church’s social-religious-political-civil setting—as Jesus was on trial, so is the gathered-church—not just for judgment, but to affirm their allegiance, for encouragement, despite all appearances to the contrary, Jesus is king! As I said already, this scene is good news to the church!

The gospel shaped gathered-church is not simply one of social integration, but is a scandal to any human institution that systemizes tiers of human hierarchies, be it social, civic, or religious. More than simply a model, everything about the early, locally gathered-churches challenged the empire, the temple-cults, the religious and political establishment, the business world, and, supremely, all human relationships.

Celsus, the second century critic of Christianity, described the spread of Christianity as a religion of “slaves, women and little children,” a warning and an argument against the church, for it disrupted the status quo ordering of life. It was “unlikely that Celsus would have thought the Christians worth his notice had he not recognized something uniquely dangerous lurking in their gospel . . .” These gathered-churches were made up of unequals and strangers. Their gatherings were seditious and dangerous at two levels: social (the leveling of social status) and empire (another king). Their presence, like no other, threatened to destabilize all of society. It is no shock, then, that the church was scorned and persecuted. Yet, the church lived in the tension and conflict differently (than other rebellious sects and groups) . Like Jesus and his kingdom, the church will not be defended (or grow) by the world’s means. By any form of violence or appeal to power. Yet, we turn too often to the powers to get our way, to defend our plot of ground, to promote our agenda—way too close to the duplicitous Jewish leaders’ use of Caesar’s power through Pilate. The very opposite of Jesus before Pilate. The Ephesus church would later hear from the Apostle Paul that the gathered-church's fight is not against blood and flesh, but against the spiritual powers in the heavenly places (6:12) . . . our struggle is always to keep Jesus before our accusers and we must stop making our gospel, our stake of ground, our values a fight between our neighbors and Caesar.

You see, this cup would have been raised throughout the Roman Empire at this time, at every household supper gathering (an evening household banquet, if you will) . . . this is where the church would have declared openly, in front of each other and guests and onlookers (remember, the uninvited would crowd around these suppers to see what's happening)—this is where they would risk everything, set things right, and declare that they had no king but Jesus!

[1] David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 167. *This message was originally delivered at Christ Presbyterian Church Fairfield and Christ Presbyterian Church in The Hill.

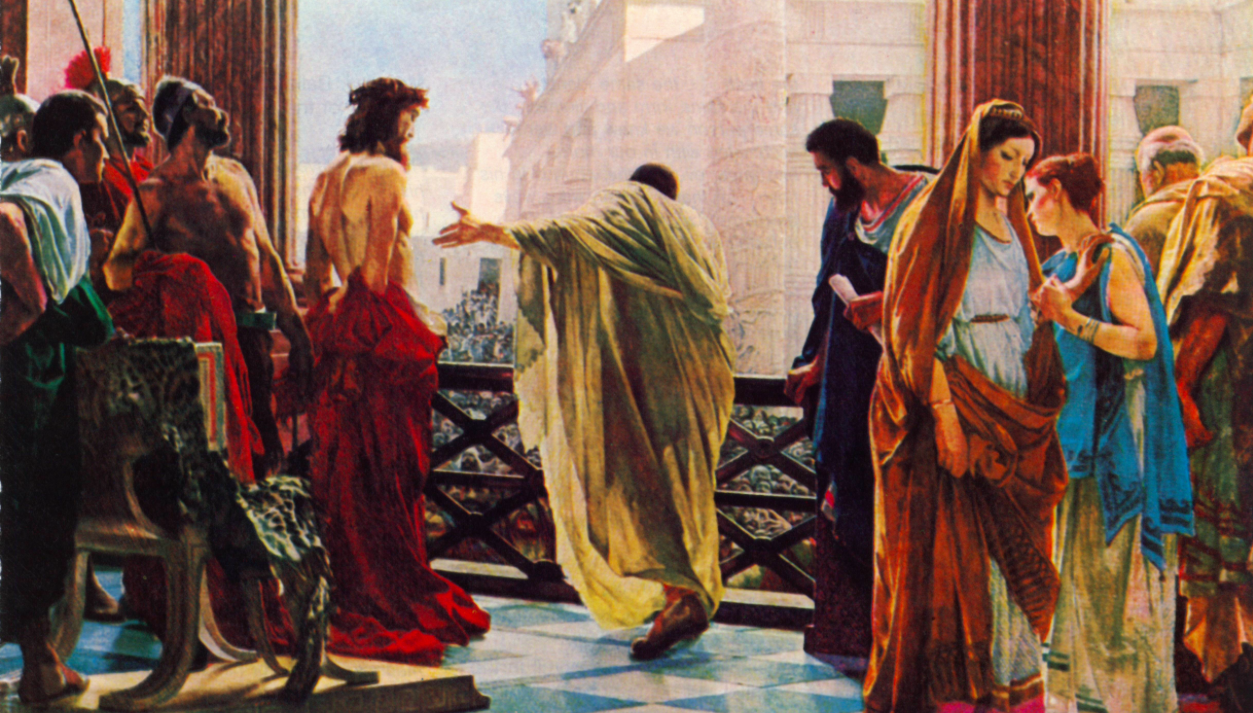

II. This scene tells us we serve another king and is the gospel to us, the church The second of our Pilate-questions comes to us in v. 33, “Are you the King of the Jews?, and suggests that Jesus is no ordinary accused. This question sets us (the listeners of the story) up to realize we belong to another kingdom and serve another kind of king, that our belief and church habits should affirm this in our gathering and in our discipleship, in how we do church. As Paul pulled from an early liturgy in Phil 2 (And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross, 8) and certainly his the “Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed” (1 Cor 11:23), the church early on began to remember the events associated with what we call Passion Week. Some of the earliest Christian art portrayed the scenes in this episode of Jesus before Pilate, an indication of their importance in the habit and devotional life of the early church . . . “that which we have seen with our eyes and our hands have handled,” later John tells us—and then we have the creedal, “He suffered under Pontius Pilate.” God died–not in legend, not symbolically, not in a distant past, not in some mysterious realm. The gospel story is brought down to earth and made a part of the life of the church, a part of the life of a gathered-church. Each Sunday Christians everywhere make as part of their confession two names: Mary and Pontius Pilate. Mary’s name as part of Christian creeds is no surprise, but something should jar us about the inclusion of Pilate into the church’s liturgical memory. Karl Barth once said that running into Pilate’s name in creedal recitation was akin to the movement of “a dog into a nice room.” This scene in John’s Gospel has been etched into the memory and habits of the church for centuries. We hear it in the Apostles Creed:

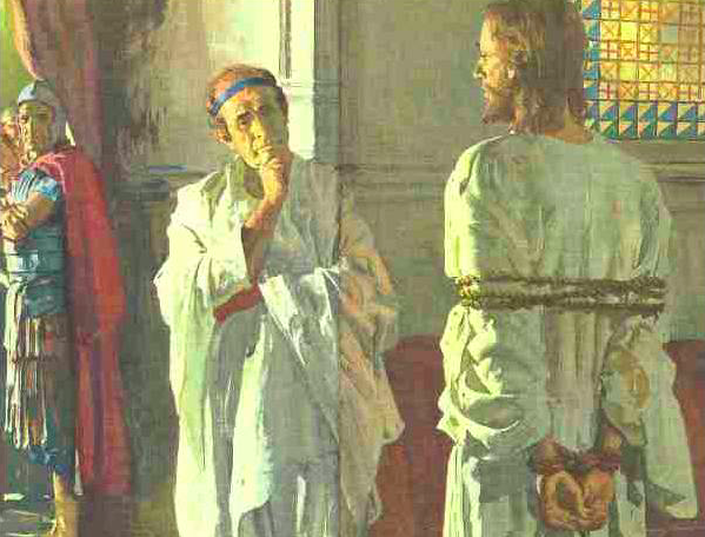

What I find interesting is that the Pilate-Jesus scenes are a part of early household baptisms. Before we moved from gathered-household churches scattered across the empire to Caesar-sanctioned buildings, we have an account of a baptismal service from Hippolytus of Rome (about 200 AD): The candidate to be baptized would be asked: “Do you believe in God, the Father Almighty?” The baptismal candidate was to say: “I believe.” Then just as the rite of baptism took place, the one being baptized was asked: “Do you believe in Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who was born of the Virgin Mary, and was [wait for it . . .] crucified under Pontius Pilate . . .” Christians began their life of faith with a confessional connection to Pontius Pilate. Later in the Nicean Creed, about 325 AD we read (we recite), “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven . . . For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate.” For our sake . . . the initiation and weekly confession of our faith was linked to . . . Pilate and Jesus We don’t know much about Pilate. We know that he was a Roman prefect over Judea and we know that he was married. Dorothy Sayers wrote: the importance of Christ before Pilate is that we no longer behold God-in-his-thusness, as transcendent, abstract, and universal, but rather God-in-his-thisness, as embodied in the person of Jesus, as immanent, concrete, now encountered as triune. Indeed, we are face-to-face with the shocking particularity of the Christian faith, made more scandalous by God’s weakness and poverty in the person of Jesus. Sayers reminds us that the threats of those in power mean nothing to those prepared to die, to those who know that dying and suffering is not the worst thing we do as human beings. The truth rests with those who, in humility, are not afraid because they know what is beyond this life–they know a different king and belong to a different kingdom. In this confrontation between Jesus and Pilate, the battle between the powers of this world and divine power comes to a pen-ultimate climax, with Jesus acknowledging Pilate’s limited culpability when Christ tells him “You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above.” Pilate’s question in 18:39, ‘What is truth,’ exposes the perplexity of a person who is a stranger to himself, uncomprehending and confused, so very short of the freedom proper to human life (Sayers). But this is the same space the church occupies amid outsiders, for we know the truth. There is narrative parallel here between Jesus’ kingly authority and the mention of truth. In his Gospel, John closely webs Jesus’ presence and authority to the concept of truth:

And in our scene this morning (v. 37): “. . . for this purpose (Jesus says to Pilate) I have come into the world—to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth listens to my voice.” It is here that the Accused calls his judge to repentance and to choose what does not appear to be the case in that judgement hall. Jesus opens a path to faith for Pilate to believe Jesus is a king and has kingly authority: choose Christ or choose Caesar. The One in the dock (the old English word for the place of the accused in a courtroom) invites his judge to be his follower, to align himself with those who are “of the truth,” to deny Caesar. In this Jesus is very dangerous to all who have power. Isn’t this our calling? Isn’t this the church, a local gathered-church, set at the end of accusation . . . calling our accusers (the skeptical, the unbeliever, those that misunderstand us, those that judge us fools and foolish) to join us, to deny Caesar and all the powers aligned against God and to follow the One who went to a cross because that is the only way for life to happen, the only path of resistance to the powers of this world.

Isn’t this the sphere and place of church: we confront our accusers (outsiders on that wide range of skeptics to haters) in our worship and in our mixed gathering of unequal strangers with the presence of Christ, to create an opportune space to acknowledge Jesus as king? The tables are turned in a gathered-church. It is our very presence, it is the witness of the very presence of the church, as it stands before Pilate if you will, before our neighbors, family, and friends, that opens the choice: choose Caesar or choose Christ . . . And for us, right here, right now: If Jesus’ claims are to be believed and investment in the church is to be had, despite social, political, religious, and familia pressures to abandon or compromise, then the nature of Jesus’ authority, the nature of his kingship need to be clear—at the most critical moment, right here before Pilate (when life or death is the apparent choice) it is made very clear. This claim, the fledgling, persecuted, maligned, powerless church needed to hear, just as we do as a gathered-church right here: Life nor salvation would not be found in the temples that Caesar used to maintain his control over his empire; but, in the One standing before Caesar’s proxy—life and salvation is only found in the One who suffered under Pontus Pilate. Even this awful scene, despite all appearances, is gospel especially to a gathered- church.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is one the most influential novels in American history. I betcha didn’t know it has a subtitle: Or, Life Among the Lowly. Released in 1852, second best-selling book of that century only to the Bible. Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicted the reality of slavery, and, to some, helped to lay “the groundwork for the Civil War”[1] A southerner reported saying that this novel “had given birth to a horror against slavery in the Northern mind which all the politicians could never have created” (David S. Reynolds). Even Abraham Lincoln, upon meeting Harriet Stowe, famously said, Is this the little woman who made this great war? I love to tell stories. My daughter says, “Dad, you have a story for everything.” She didn’t say I had lots of stories, but for everything I had a story. Stories are for the hearer—they do something for those who listen. Just like Uncle Tom’s Cabin had unleashed “this great war” to help end slavery, so the Gospels are for changing us, motivating us, the gathered-church . . . no wonder God created the “Gospels” to immortalize His story to his gathered-churches. I’m persuaded the Gospel of John was written in Ephesus and its audience was the household churches throughout western Asia Minor. These house gathered-churches were filled with believers who had had a very cultural, pagan temple-life, centered around the Roman empire, the Caesar-cult, and multiple deities, regional, local, and even household amulets; and, who celebrated this life at regular “suppers” of gathered guests and peers (known as diapnon). I know Pastor Andrew has drawn out the temple themes in John’s Gospel—and this should be no surprise, for as the gospel had so disturbingly penetrated the Gentile world and now . . . believing Gentiles and households of worshipping believers needed to learn a different temple-life. One that looked and felt more like a living room filled with unequal strangers . . . one that was treasonous to Caesar and the empire rather than one socially and culturally safe and approved by Caesar—or, like now, safe in a Christianized culture. What would this episode in John 18-19 mean to those young household churches of mostly former (and some, for sure, still) temple-worshipping Gentiles; of families empire-dependent and encultured by pagan temple-life? In some way, this switch from going to temple and living a temple-habit life, in and out of one’s home, has some bearing on how we are to hear this epic set of scenes in John’s Gospel of Jesus before Pilate. The question before us in this episode isn’t just historical (e.g., nice things to know about Jesus), but how does it speak to us as church? Not insights for our privatized Christian lives, but a story for church, a gathered-church, for Christ Presbyterian Church Fairfield or Christ Presbyterian Church in The Hill. As with any story, we should ask with whom do we identify? We’d be splitting hairs over identifying with the Jewish leaders or the crowd or with Pilate. Let’s not say Jesus . . . not this time. As with the nature and purpose of the Gospels, I say, it is the readers with whom we are to identify: what does this text mean for those early Christians and what is its significance to us, the gathered-church right here, right now? There are lots of questions Pilate asks throughout this scene. John harnesses them as platforms for the listening gathered-church to hear and respond themselves to this story . . . there are three questions in particular that help us through this scene so we may respond as church. I. This scene orients us toward fulfillment—it calls the church to have patient-trust in God’s fully capable providence The first of our Pilate-questions comes at the scene’s beginning, verse 20: “What accusation do you bring against this man?” Though Pilate is asking the Jewish leaders to determine if Jesus should be before him in the first place, this question sets up the listener to learn that Jesus, despite all appearances, was before Pilate because God had put him there. John records for us in 18:31-32 Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law.” The Jews said to him, “It is not lawful for us to put anyone to death.” This was to fulfill the word that Jesus had spoken to show by what kind of death he was going to die. Later, in 19:10-11, after the Jews challenged Pilate’s authority, which made him fear, we hear Pilate demand of Jesus: “You will not speak to me? Do you not know that I have authority to release you and authority to crucify you?” Jesus answered him, “You would have no authority over me at all unless it had been given you from above . . .” In this, we should detect the plan of God. Jesus is right where God put him. The opening scene links the Jewish temple-leadership and the Roman imperial power together (18:28–32). After Jesus’ arrest, he is led from the house of Caiaphas, who was High Priest, to the governor’s headquarters to get Pilate to exam him. Although Pilate was a weak regent for Caesar in Judea, with him there, Caesar was there in that judgment hall nonetheless. And, despite appearances, the presence of Jesus was confronting temples and temple-powers. Yet, we should also note well the hypocrisy of the temple-leadership exposed here: “. . . They themselves did not enter the governor’s headquarters, so that they would not be defiled, but could eat the Passover” (v. 28) They are willing to use the power of Caesar to do their dirty work in doing away with this troublemaker to their own established authority. Yet they didn’t want to touch the heathen plot of ground—they didn’t want to appear polluted, contaminated and so be denied the Passover. This is significant in that they knew full well that turning Jesus over to Pilate and in short order making it all about Caesar’s authority was to condemn Jesus to crucifixion. The irony: manipulating the political system to kill off the true Passover—1 Cor 5:7, Christ our Passover has been sacrificed. Here, too, we should detect the plan of God.

The first Christian book to be penned by an early church leader, the very first, do you know what the subject was? Tertullian penned Of Patience about 207AD. But when the Lord says this about the flesh, pronouncing it “weak,” He shows what need there is of strengthening, it—that is by patience—to meet every preparation for subverting or punishing faith; that it may bear with all constancy stripes, fire, cross, beasts, sword; all which prophets and apostles, by enduring, conquered! (Chapter XIII) A second general Christian volume comes to us from Cyprian of Carthage at about 257 AD. Guess it’s subject? The Advantage of Patience. What is so fascinating is that Cyprian linked patience to that scene in John’s Gospel of Jesus and Pilate: Surely, He who was not rebellious, neither contradicted, when He offered His back to stripes, and His cheeks to the palms of the hands; neither turned away His face from the foulness of spitting. Surely it is He who, when He was accused by the priests and elders, answered nothing, and, to the wonder of Pilate, kept a most patient silence. . . (No. 23) This is the first thing: As a church we need, despite all appearances, to have a patience-trust in God’s providence. Imagine the trust and patience that they needed . . . no leverage, no power, disconnected from everything that gave life meaning (no temple, no protection from honoring Caesar, no affirming the tiers of human-hierarchy that sustained the life of the empire), nothing but their fellowship of unequal strangers, somewhat unlawfully meeting in someone’s home . . . Jesus standing there at the end of Pilate’s (really Caesar’s) judgment . . . we, too, must have such patient-trust that we are right where God has put us as a church

I have come to the end of my study and preparation for a sermon on the John 18-19 episode of Jesus before Pilate. Here are some final thoughts: In the final scene of this Passion-week episode our attention is drawn to Pilate’s last question. He could find no guilt in Jesus, “Shall I crucify your King?” This question sets up the statement of all adamic statements: “We have no king but Caesar!” The Jewish leaders themselves had become frustrated with Pilate and, so, they turned to the clincher of their argument for doing away with this Jesus–they made it all about Caesar. They do what the world always (and the church, all too often) does: they change the characters in the judgment hall. They put Pilate before Caesar rather than Jesus before Pilate. The Jews set Pilate up, for when “Pilate sought to release him” (19:12), the Jews cried out, “If you release this man, you are not Caesar’s friend. Everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar.” And in their last breath, the words that confront us all, Pilate was done—out-done: “We have no king but Caesar!” The ironic thing, the Jewish leaders didn’t want to defile themselves by going into Caesar’s Jerusalem judgment hall, yet they had carried Caesar in their hearts, leaving them most defiled and guilty at their very core before God. As he had tracked the Jewish leaders and Pilate down to that very moment, Jesus puts every listener of this story, every church, all of us on trial. Who is your king? But I don’t want to leave this here before the individual—which of course you must decide who is your king? —but I think we need to go right to the listeners of this in its original setting and see how this all works for church, for the gathered-church. This scene parallels the church’s social-religious-political-civil setting—as Jesus was on trial so is the gathered-church—not just for judgment, but to affirm their allegiance, for encouragement, despite all appearances to the contrary, Jesus is king! This scene is good news to the church!

“He who dies with the most toys wins ” – What would it take, really take, to make you content?3/16/2018

What would it take, really take, to make you content? . . . to make you happy? . . . to make you satisfied? A fancy pickup truck, stocked with all the options, passed me on US Interstate 95 in Connecticut. My ancient mini‑truck was dwarfed by its size and flamboyance. I had a sense of feeling cheated. There I was, put‑putting along in my multicolored, very used ‘74 Chevy Luv. And, there was this guy, flashing by me in his shiny new behemoth. As he passed I noticed a bumper sticker neatly pasted to the thick and bright, shinny chrome rear bumper. He who dies with the most toys wins As far as the world with its toy-ish passionate pursuits was concerned, I was the obvious loser. But, I, in my aging pickup, knew something that fellow didn’t. Perhaps I should say I knew Someone he didn’t. When life consists of items of purchase and the fulfillment of temporal pleasures, the result is meaninglessness. The writer of Ecclesiastes cautions us to be careful where we look for contentment: So my heart began to despair over all my toilsome labor under the sun. For a person may labor with wisdom, knowledge and skill, and then they must leave all they own to another who has not toiled for it. This too is meaningless and a great misfortune. What do people get for all the toil and anxious striving with which they labor under the sun? All their days their work is grief and pain; even at night their minds do not rest. This too is meaningless (Eccl 2:20–23). I am amazed at the attitudes of my contemporaries. I am even more aghast because so many among the community of faith have been seduced by similar attitudes. Whether it is instant success, material affluence, or bigger and better churches, we believers can be accused of exchanging the Christ‑life for life as the world defines it. I am not a fan of Christian designer tee shirts. Much of what is plastered on them comes close to sacrilege. But I was pleasantly surprised by one shirt that mocked the boastful arrogance of that trucker’s life verse. It read: He who dies with the most toys still dies. A Vital Truth That slogan catches the essence of a vital truth. Christians, of all people, ought to know that this world and the things of this world are passing away (1 Cor 7:31; 1 John 2:15–17; Matt 7:24–29). Yet we have fashioned our criteria for meaningful spirituality and meaningful church life from the world’s models. Affluence and the American ideas of success and freedom are what count. But death, the common denominator, will expose our vanity in striving for the wind—striving for a world‑given, culture‑driven contentment. I ask the question again. What will it take to make you content? Perhaps our problem is rooted in how we become content. We have reduced contentment to its lowest common denominator—items we buy and feelings of comfort. Paul’s final words to the church at Philippi raise the Christian idea of contentment to its proper sphere. True contentment flows from a commitment to something worthy, something eternal, something beyond us. True contentment flows from a commitment to the gospel. We have come to the exhortative section of this letter in Philippians 4:1–20. The last half of it (4:10ff) is highly informative regarding Christian contentment. Before this the apostle exhorted his readers to imitate his life (3:17; 2:17–18; 3:4–14). He says it again in 4:9: “Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me—put it into practice” (Gordon Fee). There is no doubt that in this closing section, Paul continues to suggest that he has modeled the authentic Christian life, the deeper life. Restless Christians struggling to find contentment give rise to a self‑interest mentality within church communities. That, in turn, results in ill health for the Body of Christ. In 4:10–19, however, we discover a strong and dynamic connection between Christians’ level of contentment and their commitment to the gospel--and, as Philippians has been emphasizing, their commitment to church.

The passion week scene of Jesus and Pilate has provoked many thoughts for me as I prepare for this year's Easter season. I mentioned in a previous post that we ought to identify with the readers of this story and listen closely as they would have to John's telling of this story, and in particular the scenes of Pilate and Jesus (in John 18-19). This scene was an answer to them, as it still remains an answer for us, this is how things change–this is God's way to change the world, destroy powers, and save humanity (our friends, family, and neighbors, even our enemies). Looking to Ephesians for a moment: I am persuaded that the Gospel of John was written by John in the Ephesus area and its first audience was the gathered-churches throughout western Asia Minor (similar as Paul's Letters to Ephesians and Colossians). So, I start with Ephesians. Most take Paul’s Ephesians letter as an issue-less document (e.g., no real problem in the church) and crafted in such a way to address the church universal rather than the church local. Nonsense. Absolute nonsense. The Letter was written to the local churches—ye, household gathered-churches—throughout western Asia Minor . . . and given Ephesian's highly liturgical and hierophany-like nature, its temple-ish and sacred space framing . . . I take the issue to be: the gospel had so penetrated into the Gentile world that former pagan-temple worshippers entering into church fellowship needed to learn a new temple-life as church, something wholly different that there temple life in Roman, pagan culture and society. In this case, a gathered church that looked and felt more like a living room filled with unequal strangers, wives and husbands, children and slaves, and extended family . . . than a theater-like building with mostly equals sitting in pews . . .  What would this scene, Jesus before Pilate, mean to the young church of mostly former (and some, for sure, still) temple-worshipping Gentiles and a number of Greek-speaking diaspora Jews living in western Asia Minor? We must acknowledge and grasp that there is no New Testament analogy for what we do on a Sunday morning. We’ve exchanged someone’s dining or upper room in the greater Ephesus or perhaps Laodicean region for a theater-like building that Caesar (now) sanctions. We have exchanged a meal, a diepnon or supper, with the broken break shared at the beginning of the meal to signify all those gathered at table were in Christ, a family, made one because of Jesus’ broken body on that criminal’s cross (cf. Eph 2:11-22) and where a cup would be raised after the meal (cf. Luke 22:20) to honor, not Caesar or a household deity, but the resurrected treasonous-traitor, Jesus, the real and only King of kings and Lord of lords, the One standing before Pilate–all exchanged for tokens and symbols rather than a gathered-church of unequals and strangers, poor and wealthy, beggars and doctors, the discarded and the elite, the temple prostitute and the patron, slaves and masters, orphans and male child-heirs, girls and children of slaves, women and men . . . this was the way to destroy the gods of the Greco-Roman empire and to topple a Caesar. There was only one king in that judgment hall. The one wearing a crown of thorns, bloodied by a criminal's beating, fist marks on his cheeks, in a mock purple robe. You see, we hear the passion-week inquisition where Jesus stood before Pilate with strange ears to the story . . . but . . . hear again we must . . . again, differently . . . we must cry out, 'We have no king but Jesus!' and abandon all our idolatries and allegiances to the kings and powers of this world. As it was for those early gathered-churches in western Asia Minor, so still for us: this is how God destroys the powers and changes everything. All the Wasted Passion Week Thought blogs >> Click Here

Wasted Passion Week Thoughts: “Show hospitality to one another”–– It's not what you think (really)3/5/2018 Some percolating thoughts on next week’s (3/11) sermon passage, 1 Peter 4:8-11, and in particular verse 9 in this context (see the last set of words and you will see why as you read my thoughts below):

Can’t get around it: NT (expected) hospitality was risky business. First, it was (as it should be now) developed around unequals and strangers, aliens to one’s own patria (family), peers, and peeps; and if expected hospitality (e.g., 1 Peter 4:9) is for the purpose of opening one’s home for worship, instruction, and fellowship—that is to be the space for a gathered-church—that gathering would be, by its very nature and habitus, subversive and treasonous, for not only would it upset and upend the cultural norms that stabilized the social order of the empire, a cup would be raised to celebrate and acknowledge that the dead-but-now-risen-traitor-criminal Jesus, not Caesar, was Lord and King—and coming again! Our modern expression of church does not fall under this type of hospitality (space), which needs to be—per the NT, really, ought to be—a part of our ecclesiology. The empire (i.e., our culture, social associations, and government) does not consider us too much of a threat in how we meet or who meets with us. What I find interesting is that when a church does start to act or envision church in this hospitality-way, it is a threat to the existing church. What’s up with that?

Wasted Passion Week Thoughts: Jesus' authority needs to be clear, if the church is to survive3/2/2018

As with any story, we should ask “who do I identify with" in the larger John 18:28–19:16 story? More importantly, who does the author expect his readers to identify with? To be honest, we’d be splitting hairs over identifying with the Jewish leaders and priests, or the crowd, or with Pilate. All of these are certainly possible. And, please don’t say Jesus . . . not this time, in this story, anyway. This time, however, it is the original readers that we should be identifying with as we read and place ourselves in this story. So, what was it that the original audience of Ephesus area, Asia Minor gathered-churches were to hear? So, just a thought . . . as we, our own locally gathered-churches identify ourselves in the story . . . If Jesus’ claims are to be believed and long term commitment and investment in the church, really a local gathered-church, is to be had, despite and amid social, political, religious, familia pressures to abandon or compromise, then the nature of Jesus’ authority, the nature of his kingdom need to be clear. It is made very clear in that scene before Pilate. Jesus' kingship and kingdom is not of this world–and doesn't defend or act in accordance with the powers of this world. This scene parallels the church’s social-religious-political-civil setting--as Jesus was on trial so is the gathered-church. So, this claim, the fledgling, persecuted, maligned, powerless church needed to hear. Life nor salvation would not be found in the temples that Caesar used to maintain his control over his empire; nor in the Roman house where a cup to Caesar would be lifted up at a diapason (a social supper where people were invited to come and recline); but, in the One standing before Caesar’s proxy—life and salvation is only found in the One who suffered under Pontus Pilate. All the Wasted Passion Week Thought blogs >> Click Here

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed