Idolatry and Poverty: “idolatry comes naturally to us" (samples from a chapter in Wasted Evangelism)6/25/2017  Christian responses to poverty often draw from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5–7; Luke 6), further substantiated by other NT teaching (e.g., Acts 2–4; Jas 1–2). Although important, this tends to be applied more to church-life and to the private sphere rather than developing a response to those living with the effects of poverty. Others turn to the Pentateuch and the Prophets, and, rightly so, for such biblical material is rich in addressing the issues of poverty. The results, however, can tend toward justification for political alignment and socio-economic policies (right/left, conservative/liberal). Christians across the spectrum wrestle with how the Pentateuch and the prophets apply in the (post)modern world. Many question the contemporary relevance of such documents of antiquity addressed to an ancient nation whose social-political location is the Ancient Near East. Nonetheless, there is a way to decipher the significance of OT ethical texts, namely to draw significance from their incorporation into the gospel itself. Mark draws upon a fascinating range of OT contexts throughout his narrative that juxtapose idolatry and the economically vulnerable. Although Mark’s use of the OT is extensive beyond these particular texts, he embeds his Gospel with OT contexts related to the economically vulnerable, whether Law, land-stipulation, or prophetic announcement, which also contain, within the context or flow of thought, mention of idolatry.  The juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty in Exodus and the memory-judgment context in Malachi bear out the apologetic framework discussed above. Additionally, Mark’s constant use of Isaiah also reinforces this framework, which is particularly vivid in Isaiah 40, a component of Mark’s programmatic summary. Mark’s Isaiah referent itself--A voice is calling, “Clear the way for the Lord in the wilderness; make smooth in the desert a highway for our God” (Isa 40:3; Mark 1:3)—carries imagery common to Isaiah’s world, reflecting the procession of ANE monarchs. Here, Yahweh comes as Victor-king, announcing the Good News (v. 9), where all flesh will see the glory of the Lord (v. 5). Isaiah 40 then compares Yahweh to surrounding idolatrous nations, which are like a drop from a bucket (v. 15) and are as nothing before Him . . . less than nothing and meaningless (v. 17; note v. 23). Mark’s introduction contrasts the gospel to the concept of the imperial cult of Caesar linking it with the apologetic of Isaiah, emphasizing the incomparability of Yahweh, whose sovereign power over creation is boasted of (v. 12) and affirmed to be in need of no-one’s counsel regarding justice (vv. 13–14). Yahweh is distinct from the image-bearers made of gold and silver who need to be fashioned by human-hands (vv. 19–20), for he sits above the circle of the earth and stretches out the heavens like a curtain (v. 22). The Holy One takes on all-comers: To whom then will you liken Me that I would be his equal? (v. 25). Isaiah notes the starry hosts (v. 26), each representing idolatrous pagan powers, yet it is Yahweh who created them and calls them by name, indicating his might and strength over the idols of the nations.  Mark’s consistent references to OT material that juxtaposes idolatry and the poor is certainly embedded into the very nature of the gospel, suggesting that the gospel is formative for social arrangements. Mark’s highlighting of these OT texts that juxtapose idolatry and expectations regarding the poor, as well, points to an apologetic and evangelistic potential for social action. Still, moving from ancient text to significance to application can be very difficult, especially as we consider how the application of such texts can include social action outcomes. At the risk of over-generalization, even Christian approaches to poverty tend to align with political views, party affiliations, and social-locations: Politically conservative Christians tend to read capitalism, free markets, and individual charity as biblical solutions to poverty; the politically liberal tend to read more public, state-centered solutions. Although both find some textual support, neither consider the biblical juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty, nor our own human capacity for idolatrous alignments in our own social-locations. L. T. Johnson reminds us that “idolatry comes naturally to us, not only because of the societal symbols and structures we ingest from them, but also because it is the easiest way for our freedom to dispose itself.” Shifting the issue of poverty to the realm of discipleship and apologetics focuses our attention on the social-location of non-poor Christians and their relationship to the poor. In light of the gospel framed by Mark, non-poor Christians should be mindful of the idolatries that can form their own social reality, particularly those experiencing everyday life in places where poverty is not concentrated (i.e., non-urban life). It is not necessarily how OT ethical texts apply to our modern social-location (although important) that is significant, but how the apologetic nature of the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition relates to those who are to be formed by the gospel, then, how that significance dissuades Christians from conforming to any private vs. public dichotomous response to poverty.

1 Comment

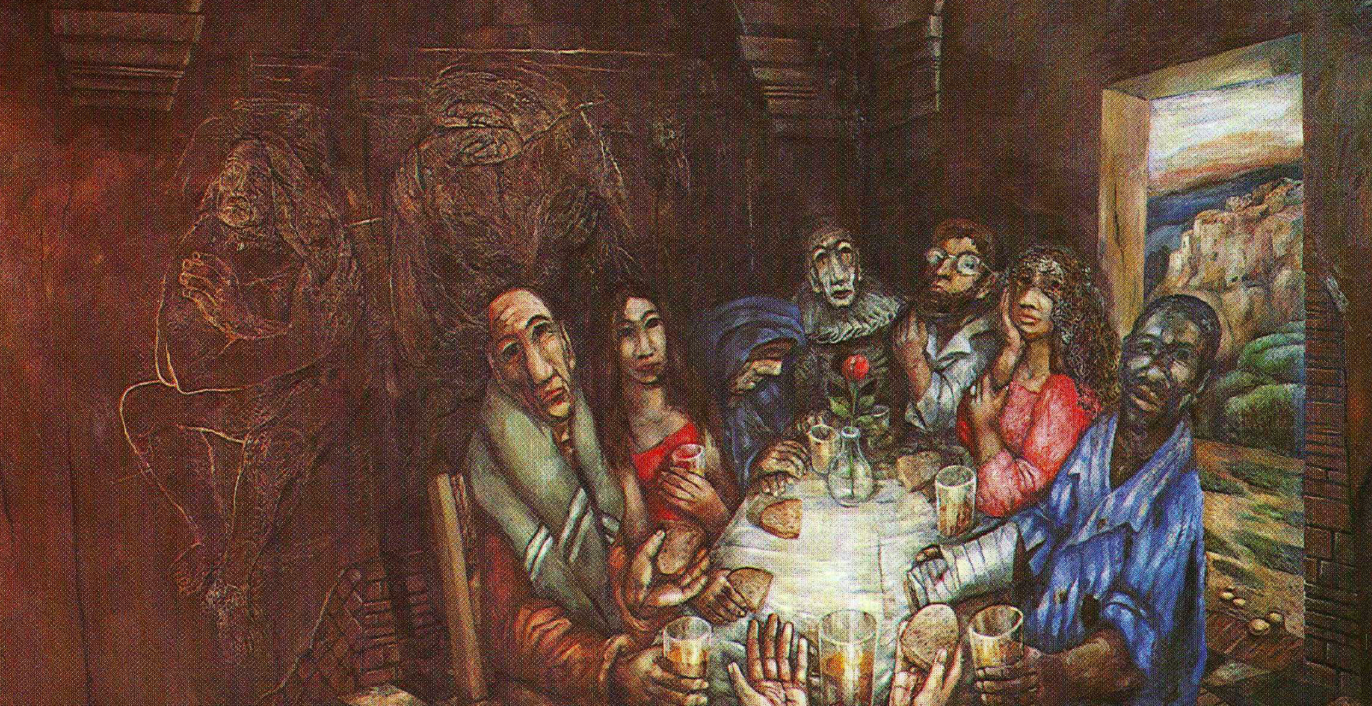

Been dwelling some in Luke’s parable of the Father, stay at home son, and the prodigal son. First, the trio-parable set in Luke 15 is not about our individual salvation nor a focus on simply the Father’s love for me--it is incredibly more and speaks loudly to the habits and the forming of church. We need to hear how, in fact, Luke starts chapter 15: “Now the tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribes grumbled, saying, ‘This man receives sinners and eats with them’ (vv. 1-2). So, the issue is pretty clear: The temple-leadership had a problem with Jesus’ welcoming of the unclean, marginal, socially unacceptable and despised to the table of fellowship. What is often overlooked in the wider context is that Luke’s chapter 15 set of parables is surrounded (preceded and followed) by “feasting” and “eating” lessons. (We’ll get to this in a moment.) Additionally, Luke’s three-parable set is also about “feasting” and “eating.” For in both the first two Luke 15 parables, after what was lost is found, there is a gathering of friends and neighbors for rejoicing: “And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost’” (v. 6). Likewise when the prodigal son returns, he is welcomed into a feast as the honored guest (vv. 24-27).

The wider narrative in Luke suggests that it is whom we invite to these “feasts” and times of “eating” that is at issue. For Luke 15 is bracketed by chapters/stories of "feasting" (i.e., "eating"). First, there is the parable about proper kingdom table etiquette (the inviting of the marginal and socially unacceptable) vs. the acceptable social norms (chapter 14) and, then in the preceding chapter, the story of a rich man, who “feasted sumptuously” and poor Lazarus, “who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man's table” (16:20-21). The lost-dead-prodigal-son isn’t just a picture of the wayward sinner, the lost law-breaker, but is a figure representing--to keep with Luke's theme--the socially unacceptable that are now welcome, equally, without hesitation or qualification (save faith) to God’s kingdom table. These parables, including Luke 15's parable of the prodigal son, are forming for church and missional church-life. Luke 15 is one of the parables that scream out: “Go do likewise!” Who are you eating with? Who are you intentionally inviting and compelling to come be a part of your local church? Maybe even more so, who are you making second class citizens of the kingdom by how we do church?

Most take what Jesus says here in a self-protecting and spiritualized manner as if Jesus said, “I have not come to call the [self] righteous but [all] sinners [that is, those who recognize they are sinners] to repentance.” But this is not what Jesus said nor meant at all. “Righteous” and “sinners” are titles, stock terms, totally recognizable to the audience at that party. “Righteous” are those who keep the law of Moses, who have recognized status and position in and among Israelites; more narrowly to temple leadership and Jewish leaders of the Pharisees and Sadducees. “Sinners,” on the other hand, are the uneducated in the law of Moses, shepherds, outcasts, the disfranchised, Jewish tax-collectors for Rome, the working class, the poor, beggars, and slaves. This is made clearer by the Pharisees and Scribes pointing out, “Why do you eat and drink with tax collectors and sinners?” One cannot get around the social and cultural location embedded in this: The Jewish tax-collector for Rome, Levi puts on a banquet-meal for Jesus, who is to be the honored guest and symposium speaker for the evening. Jesus clearly states that he had come to call [probably the idea here, given the setting, "invited" to Jesus’ banquet-meal table], not the Jewish temple leadership, but social and religious outcasts. Jesus describes his banquet-meal and table as one of social leveling and transformation, along with the purposeful association of those considered outcasts and disenfranchised. We tend to generalize and uproot Jesus’ terms the “righteous” and “sinners,” so as to keep our categories of people comfortably and neatly in place. But in the end, Jesus still upsets our social categories, for this is the nature of the gospel of the kingdom. We need, in light of this text, to rethink "church" and "evangelism" and the importance use of meal and table as a venue for creating new social spheres and acceptance.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed