Living out, both as individuals and as a gathered-church, the Sermon of the Mount, should appear as a threat to the social and cultural status quo and to those invested in maintaining this status quo. As such, Sermon on the Mount living cannot help but challenge the way things are. Interestingly, in the Sermon on the Mount there is no mention of ranting on public platforms as the means to challenge the powers, no mention of protesting or boycotting, no calls for platforms to leverage any form of power, no voice nor stones–only light and salt (i.e., living in community, that is as church); rather we are not to practice our righteousness hypocritically for the applause and/or affirmation of others (and you don't get invited to be an A-list Christian speaker without that applause), not to judge, and are to do to others how you want to be treated (no matter how you are treated by them). Living out the Sermon on the Mount is meant for church, a social group whose allegiance is to the risen Lord Jesus, not to be attempted solo, for apart from the gospel at work in the flock of God, encouraging one another and loving one another, such living is impossible. The Sermon on the Mount is not possible for the State to legislate by law apart from granting power to some to enforce by forms of punishment and violence. Surprisingly we seem to be doing the opposite. We love the opposite, because we like power, whether the power of the crowd (i.e., the mob) or the power of platformed applause. Sermon on the Mount living is the opposite of power. And, we are impatient. Sermon on the Mount living demands patience. And, we trust our leverage and platforms. Sermon on the Mount living calls for extraordinary, faithful trust in God's ability to work in the affairs of humankind, and thus to be often hidden and away from the applause of others. It is no wonder that the first two book volumes produced by the church were on "Patience" (i.e., Tertullian and Cyprian). No one, especially Jesus, said this Sermon on the Mount living is easy. This is why the gate is narrow to this life, the life imagined by the Beatitudes. We, as church and, especially, our individual elite-celebrity Christians, seek to use the wide and broad way (judging, law and thus State enforced punishment and retaliation, encouraging hatred and others to judge, and non-forgiveness, and the building of power and leverage (the complete opposite of the Sermon on the Mount), which leads to destruction. And just in case we didn't get that the Sermon on the Mount is actually God's word to his church, we are to build on the Rock of this Word and not the sands shifting power. God, forgive me for not living out the Sermon on the Mount and for being all too willing to call the church and other Christians to live out the wide and broad way to get our way in this world. *Check out as a part of this thread, Matthew 6:1-18 as a reflection on the Beatitudes >> Click Here

0 Comments

*This is the fourth instalment of quotes from my presentation on "Church (local), the poor and their neighborhood," which are somewhat random, but still focused on the church and the poor. For all the posted "Church (local) quotes >>

Yes, I posted the set of most influential books I read in 2016. Yet, there are three books that have significantly moved me to rethink my gospelology (how come that’s not a word). Granted I’ve been heading this way, but in God’s gracious providence, he allowed or choose these three books to enter publication and find their way to me. The books underscored the things God has been teaching me this year. Two words can sum up what has been taught: horizontalization and leveling. The three books are:

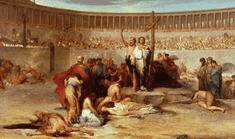

These three books, more than anything, taught me about the two words--horizontalization and leveling--and their importance for a better, more proper understanding of the gospel and church.  I am sure I will post something soon on “horizontalization” and “leveling,” but for now, it is enough to say that God has taught me that the uniqueness of the gospel is leveling, that is, there is a leveling among believers unlike anything else upon earth. The table or the partaking of the Lord’s Supper is a leveling event (or should be). Our fellowship, i.e., our church life and worship, is a leveling of our social status’s. Whereas “leveling” is what should occur among believers and through its events of worship, the Table, baptism, and living in the world, “horizontalization” is the effects of the gospel that are displayed to the world; what outsiders, nonChristians, the unchurched, and the powers should see in and through our behavior, our habits, and our systems (i.e., the way we worship, the way we facilitate the Table, the way we do baptisms, and the way we live among people and together as a church). In other words, where such social leveling occurs, the church is displaying the horizontalization of the gospel. This is what I have been taught this year. Now, let’s see if I have learned anything. Check out my sermon on John 13, Jesus’s Community of Footwashers: His Public Presence in Caesar’s Arena of Death, that offers some of the insights on what I have been taught about "leveling" and "horizontalization." There is a link on that page for downloading the sermon and for listening to it as well (if you have the time).

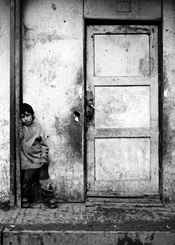

I am constantly looking for books I can give away or refer to that might move my friends, maybe just a little, to reconsider their understanding of the gospel and its relationship to the poor. Craig Greenfield’s Subversive Jesus: An Adventure in Justice, Mercy, and Faithfulness in a Broken World is, thankfully, one such book. This volume does exactly what I am looking for: it connects Christians to the issues of poverty and to the poor through reflections on the Bible and through the messiness of ministry. Greenfield points out that respectable Christians don't "throw in their lot with the poor” (22), yet he believes, as I do, that “there is a biblical mandate for Christ-followers to become lobbyists for the poor” (139). Subversive Jesus explains wasted evangelism very well, portraying the relationship between the gospel and social action through the ministry illustrations and, as well, through his autobiographical sketches of real life stories among the poor. Subversive Jesus isn’t just another book guilting Christians into helping the poor. It is as much a confession (of the struggles living out a subversive gospel) and story-telling as it is a reflection on the nature of the gospel and the person of Jesus as the New Testament portrays him. The content—yes, the rightfully convicting content—is embedded throughout the book within his family adventures in learning how to live among the poor—and as Christian neighbors. He confesses, “. . . it wasn’t long before we came face-to-face with the messiness of living on the edges of society with those who struggle—for we cannot separate the beauty and goodness of subversive hospitality from its challenges” (55). Greenfield shares their ministry of hospitality, that is opening up his home and dinner-table to the poor, homeless, and messy (and sometimes reckless) individuals who we, too, often turn away in our hearts long before we even have a table to invite them to. We are led into the vulnerability of the Greenfield family as they experience and learn learn some of the tougher aspects of home and hospitality ministry to the poor. He writes, “Those of us who practice subversive hospitality will forever live in the tension between our finiteness, our human limitations, and grace. It will break our hearts when we have to say no or close our doors” (57). Greenfield does not hold back on the exposition, that is, the power of portraying the Jesus of the gospels. He explains, “I began to understand what this upside-down kingdom on earth might look like. For Jesus’ life was bookended by an empire’s standard response to anyone who is a threat: violence and brutal repression” (24). In fact, he is right to call out church people, exposing how we have tamed Jesus to fit our more suburban (I prefer to say, exurban and nonpoor) lifestyles of home and church: “Many of our Sunday schools continue to encourage followers of Jesus to embrace a respectable Jesus, an agreeable teacher with pleasant stories to tell about how to be good. But no one would crucify this Jesus. No one would be threatened by such a bland personal morality. Instead, they’d invite this Jesus over for a cup of tea and a chat about the weather” (25). He reminds us of one of Luke's marks of the church strangely absent today: “God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them” [Acts 4:33–34, emphasis added by Greenfield] (52). The stories in the book are not prescriptive, he writes, but are demonstrations of how God worked in his life and, as well, his family’s life. He draws us into the overwhelming sense of hopelessness we can have when we are confronted by the effects of poverty and brokenness: “Who hasn’t felt like this in the face of our broken world? We can’t help feeling overwhelmed when we hear that on billion people live in slums worldwide, or that four hundred busloads of children die every day from preventable illnesses. It’s hard enough to face the challenges of our own impoverished neighborhoods and inner cities” (50). Yet, he is quick to point out that we have put too much reliance on non-church organizations and para-church ministries to deal with the poor and marginalized: “. . . we rely on soup kitchens and institutions. Instead of opening our churches and homes to the hungry, we are taught to “leave it to the professionals.” He says, “this is the way of the empire.” There is, however, hope for the poor in God’s kingdom and among Jesus’ followers. “Jesus promises that even though the empire is a cold and lonely place for the vulnerable, his kingdom on earth will be especially good news for the poor. As followers of Jesus, we need to figure out what that good news looks like as we respond to those who are suffering because of poverty and oppression, whether a beggar on the corner or an orphaned child in a slum halfway around the world” (68). Yet, we choose to live apart from the poor, separated from the people and the effects of poverty in which they, themselves, must—and mostly not by choice—live their everyday lives. “As people of privilege, we make choices every day about where we will live, where we will shop, how we will travel, and who we will spend time with. Often these choices isolate us from those on the margins of society. Our isolation from the poor shapes how we understand poverty, and it drives how we respond to it” (107) Many of us have the power (and platform) to change how we view and approach the poor and the issues of poverty—first in our own lives, then our church life, and, as well, through advocacy and example, in the world around us. But, Greenfield pin points the problem: “Those who hold the most power and authority in society are the least likely to want to change the system that produces poverty” (111). The Greenfield family understands the risk involved with following the subversive Jesus (the Jesus of the New Testament): “We realized at a very personal level that when we align ourselves with the poor and seek to be in solidarity with those Jesus called us to embrace, there will be a cost” (157). If the gospel is subversive to culture and power, what is it about your life as a Christian that is, well, subversive? I highly recommend Subversive Jesus for your own edification, perhaps as a small group reading among your church family. You will be convicted, encouraged, at times angered, and you will cry. But most of all, you will be confronted by the subversive Jesus of the gospels and pierced and humbled by a life (the Greenfield’s) caught up in the beauty, messiness, and ministry to the least among us. Greenfield is the founder and director of Alongsiders International (alongsiders.org), an organization that seeks to mobilize and equip thousands of young Christians in the developing world to walk alongside those who walk alone, especially the orphans and vulnerable children in their own communities. The Greenfields have lived and ministered for more than fifteen years in slums and inner cities in Asia and North America. Subversive Jesus is available on Amazon. And, his first book, The Urban Halo: a story of hope for orphans of the poor, is also available. Both books may also be found on Craig's website, craiggreenfield.com.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed