The systems (by design, default, and/or from unintended consequences) that are in place that create and sustain the conditions of poverty and our current social structures are near impossible to change. All the political and progressive rhetoric is ill-equipped to actually offer alternatives to the current conditions of poverty. Social boundaries, the ability for mobility (cultural, social, educational, economic, et al.) are mostly set in concrete, near unchangeable. Furthermore, those who have a vested interest in their own place and status (wealth, social, location, power) have no, sincere, vested interest (beyond appearance, mere rhetoric, or progressive voting) in changing the systems now in place. On the other hand, those in the bottom demographics do not have the power, do not live in geographic spaces, nor have the educational skills to make any significant change to the very complex, hierarchical-engendering, boundary rich, mobility disabling systems in place that keep most everybody in their social, economic, and cultural corners (socially, geographically, demographically, educationally, et al.) The spheres of government and of social-service (private and public) do not have the truly vested, self-less interests in making change. The appearance of change, perhaps. The rhetoric of change, perhaps. The political allegiance, perhaps. But not real, systemic changes that would actually release mobility beyond the current “corners.” When will we learn this, O Christian? Yet, as strange, foreign, and impossibly crazy as this sounds, the only space where the good life, flourishing, and even systemic social and cultural change to offer real mobility beyond our current “corners” or even truly be imagined is the gospel-rich church–literally amid local churches scattered throughout communities. Amid local churches where there is no earthly power being sought (even by its leadership), but the love of neighbor (and neighborhoods). Amid local churches where an individual’s humanity is honored, prized, and even died for is a result of believing in the gospel of Jesus Christ. This is the space, amid the early church, in which such change was nurtured and, albeit slowly, happened at the heights of the Roman empire. Where it actually outlived an empire. This is the space in which such changes have happened on small and large scales ever since. Where all lives literally matter; and, when there are lives deemed lesser, treated lesser, those lives matter more, intentionally more. The space where the hierarchies of tiered humanity are deconstructed and the alternative is constructed–that alternative is the kingdom of God, realized in Christ Jesus, and revealed through the church (literally through churches scattered in countless neighborhoods and communities). In the social and governing spheres where it takes power to make systemic changes, it will also take power to maintain such changes. And, this maintaining power is always violent. Furthermore, human nature (in the church we call it our sinful nature) will not, however, relinquish its desire for maintaining one’s advantage over others and freely disinvest its self-interests on behalf of others. So once systemic changes are make (where there is power to make such change), there will always be the powerful and powers that will seek to mark their place and status (i.e., those who make the laws have the power to enforce, by means of violence, their laws); also, there will always be those who obtained newly created social elite status, those who become affluent because of the changes and, then, will seek systems to exercise power (political and social) to maintain the new status quo (their new power). Thus, the boundaries remain and the violence to maintain them continue. This is not the way of the gospel; and, thus, not the nature of the church (read local churches scattered among communities, neighborhoods, regions). This is why the local, gospel-centered, gospel-rich, gospel-dependent, gospel-lived church is the only real space where such social change can truly be experienced. Church matters (#churchmatters).

0 Comments

Sabbath Pleasure: A Day for Reflecting . . . on Justice for Our Neighbors (a Sermon on Isaiah 58)8/24/2018  Think about it: Think about all the people who had to work (income earning work) today just so you and I could keep the Sabbath. Do you hear how ironic this is? I have a confession to make: I’m not a great Sabbath-keeper. Don’t get me wrong: in 40 years as a Christian (that’s a lot of Sabbaths), I can count on my fingers the Sunday services I’ve missed. I just don’t rest a lot. I haven’t had a vacation since 2011. The language of vacation, by the way, is the language of privilege and wealth more so than of the poor and oppressed. Even our 2-day weekend is historically new, starting in 1908 at some New England mills to accommodate Jewish workers and, then, the depression (1930s) institutionalized the 2-day weekend as a way to “solve” underemployment. I rarely take a full day off. Sundays are not rest: there are hospital visits, visiting families whose loved ones have died, and visiting those in drug rehab programs, et al. And, of course, Hill birthday parties. There goes my ceasing to work. I’m more a John 9:4–We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming, when no one can work–kind of Christian. In parts of Africa, water is scarce. Women and children must travel, on foot, carrying containers, to retrieve their daily water for cooking, drinking, cleaning, and bathing. Most travel far and even up to 3-hours on foot to find water–that can be a 6+ hour journey, every day! Most of the water is not potable (not clean); it is stagnant and filled with things you’d never allow your kids to put in their mouths. I think of this when I think of church planting, building a church, Sunday worship: how do these women stop and go a day without water so their families can join church worship and affirm our confession to keep the Sabbath? So, this leads me to ask: what is our Sabbath responsibility toward the under-resourced in Bridgeport or the Hill, those working 2 to 3-jobs, car-less, food-less, shelter-less, those who need to work on Sundays . . . ? Our text, Isaiah 58, is not a pleasant one and can be seen as rather harsh. Isaiah 58 will forever be a judge of our form (institutional and local) and our religious practices (habits), reproving our intentions and reminding us, as God’s people, the gathered-church in this place, what is important, what should be assumed about our habits, and what we should be famous for. I’d like to do three things this morning:

I. The honest accusations of Isaiah 58 on Sabbath-keeping

Ok, I won’t hold back! Religion, even Christianity, including our own church-life will take on form and over time will produce institutional structures and systems. These are inevitable. We have them (if you haven’t noticed). Now, these structures and systems must be maintained. Now, we need to appoint "maintainers" and give them authority that, will eventually, put the structures and systems over people. (This is what happens; it is mostly unavoidable.) That is the nature of structure and systems. And, there is always some who will have a vested interest in these “forms” and this clouds everything up--decision-making, budgets, and all the "who" which are overlords (managers) of the “forms.” Isaiah 58 comes as Israel faced exile and here the prophet speaks against how such institutionalized religion has failed to make a difference in human relationships, especially between the haves and have nots, between those of privilege and property and those of disadvantage and land-less (that is, those with scarce-to-no resources) . . . there are more possibilities, in our institution, of acquisition of things and the stink of pride that can attach itself to maintaining our Sabbath-keeping, which can drive our Sabbath experience and church-life maintenance decisions. The prophet indicates that, although the people think their behavior should win them favor with God (look, we’re keeping Sabbath!), its real purpose was to gain prominence, power, position, and, of course, possessions. With obvious sarcasm, Isaiah chides: they seek me daily and delight to know my ways . . . they delight to draw near to God (v. 2). We can outwardly be keeping Sabbath, even justifying what we do as somehow keeping Sabbath because we are seeking God, reflecting on God and his creation.

If we take the order of Isaiah seriously, by the time we get to Isaiah 58, they have experienced the Servant’s redemption (Isaiah 53). They would have received drink and their fill of food they did not have to purchase (Isaiah 55). The foreigner and the eunuch who love God’s Sabbath would have been received into the covenant family (Isaiah 56) and those who are near and those who are far would have come to know the peace of God (Isaiah 57). So, the Israelites of Isaiah 58 have tasted the Servant’s freedom, the Servant’s deliverance. Yet, what are they doing with it? Here is the problem—the beginning and end of the poem bookend the issue:

Isaiah is clear: the Sabbath-keepers were keeping the day or rest, the fasting of work, as a day for themselves, a day for their own pleasure. The New Revised Standard Version puts it well: If you refrain from trampling the Sabbath, from pursuing your own interests on my holy day (v. 13). Rather than keeping (honoring) the Sabbath, they were actually “trampling it.” Are we, today, trampling the Sabbath because we have missed the whole point of what it was to meant to "keep" the Sabbath holy? What are we, CPC Fairfield and CPC in The Hill, doing with our freedom in Christ? Are we guilty of trampling on the Sabbath because the focus is on our own pleasure . . . on our position and status in the community . . . on some declaration of our spirituality . . . on our acquisition of processions? How do we even begin to ensure we are not guilty of fake Sabbath-keeping? II. A look back at the original Sabbath commands and how they play a part in Isaiah 58 While in the Air Force, on July 10, 1978, I received Jesus as my Lord. And, I was on fire. I hung with other Airmen who were on fire. We liked to fast. It’s in the Bible, you know. Fasting was for serious Christians. We were serious Christians. Usually just a day, skipping a few chow-hall meals, you know, to get spiritual. Then we got the bright (“spiritual”) idea of fasting for three days––three whole days. We did. And we let everyone know it, too . . . sorry, can’t go to the chow-hall, I’m fasting. Skipping lunch to read my Bible . . . I am fasting, you know, three days. When the three days were over, we met up at the chow-hall and downed a lot of food. Hey, we had just fasted for three days, you know. Some mature Christians took us aside, “Guys, that’s not how it works. If you tell people you are fasting, it’s not fasting—it’s just skipping meals.” The fasting was about us. I’m glad they had the boldness to confront the future Pastor of CPC in The Hill. It’s worth noting the original Sabbath commands. The 4th commandment to keep the Sabbath does not focus on YHWH as the first 3 words do. This command centers on the extend of those who are to keep the Sabbath. However, our institutional mind plays tricks on us, hearing Moses as if he said, we are go to church, set the whole day aside to reflect on God--that’s how we keep the Sabbath, you know, we're serious Christians! But these commands say no such thing. Based on Exodus and Deuteronomy and, here, Isaiah 58, we are to keep the Sabbath holy by ensuring that our children, our neighbors, female and male slaves, even livestock (someone’s means of work), and the non-Israelite sojourner cease to work. Nothing about worship. Nothing about going to the beach or a park or pulling up a chair in the backyard to read a Christian book and contemplate God's good creation. Nope. Not a word.

[Nothing on what we are to do, but what we are not to do—and who “the not doing” extends to.]

And just in case you missed it, Moses repeats one specific people-group:

Moses repeats that even their “male and female slave” (come on, by now you know very well the term is “slave”), making for an emphasis on all, everyone are to Sabbath, not just the blood household. All were to cease to labor on the seventh day of the week. Then to offer the reason, Moses concludes in verse 15:

Let me offer a different reading for why remembering their slavery is important as a basis (i.e., the therefore) for keeping the Sabbath: It compliments the reminder, the repeat of “male and female servant" in the extend of who was to keep Sabbath. The history lesson underscores that Israel was oppressed and forced to work. The new association with YHWH, experiencing God's freedom, His deliverance, brings something new: the Sabbath command equalizes. The rest wasn’t just for the privileged and powerful. Again, Isaiah sings with some irony and sarcasm: Is such the fast that I choose, a day for a person to humble himself? (58:5). The way it is written (and to be heard) demands the answer: No that's not what that day is for. We claim the opposite as Sabbath-keepers; we claim it is a day to humble ourselves (again, nothing in the commands that point in that direction for the Sabbath day). Remember, our Sabbath–fast (the ceasing of our labor) is not about humbling ourselves (you can hear how Sunday can be turned into PR and self-fulfillment). Here’s how Isaiah 58 corrects us and what God desires:

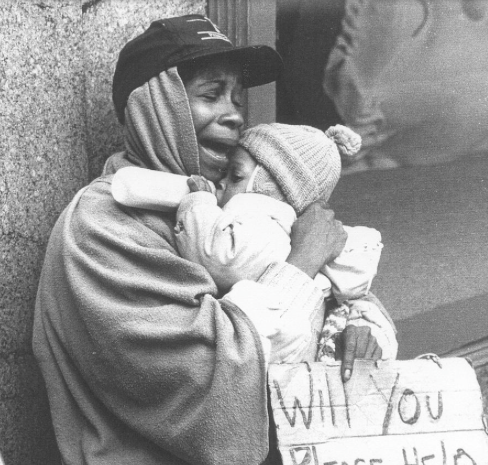

What are we doing to ensure all are equal and enjoy God’s rest? Isaiah 58 asks us, what are we famous for? III. A Sabbath–Fast that Ensures the Least and Lacking Among Us Experience Sabbath-rest Before returning to church ministry, I worked for 20 years as a community action grant-writer and program developer. We served the poorest of populations. One example: our population lacked good nutrition and underweight babies marked the population, but many could not get to the stores that had fresh produce (and if they could, travel back with all the groceries) nor could they afford food that was nutritious. Nothing in their neighborhoods. Bus routes didn’t reach where they lived. The system was against their well-being. As church, comfortable at our Sunday Sabbath-keeping, the very systems that allow us the privilege of a Sunday fellowship and worship might very well work against the well-being of the least of us. Isaiah 58 makes this connection for us. In Isaiah 58, fasting and Sabbath-keeping was their vision, but it was something for their own pleasure; yet, God had a different vision. Cultic behavior, systems, habits . . . may be self-indulgent . . . or [they] may [even] be magical in mentality (Muilenburg). Our Sabbath behavior can be turned into a device for making God do our will or to demonstrate how spiritual we are (sadly, a public display). If we truly want to cease (fast or Sabbath) from something, let us put a stop (a cease) to oppression. A) The equalizing intentions of the Sabbath will indicate God is in our midst Sabbath was a sign, but what did it signify? Exodus 31:13, states, “. . . you shall keep my Sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you . . . that you may know that I, the Lord, sanctify you.” The Sabbath-sign signified God was in their midst. Isaiah 58:8-9 affirms what the Sabbath-sign signifies: when the intent of the Sabbath is enacted (verses 6–7), then the presence of God among his people is apparent:

This is set as an if-then scenario: If we pour ourselves out for the hungry, then God will be seen in our midst. A small reflection of this can be illustrated by our CPC in The Hill summer park BBQ ministry, called “In His Midst.” When we go to the park, God is already there (we didn’t bring him) . . . so we are “in His midst.” And, because we are church in the park, the people in the park are “In His Midst.” B) Ensuring all have Sabbath pleasure, true rest, we will be the restorer of the streets It should not surprise us: the first marks of the church in Acts are the sharing of resources so no one had need. Have you ever wondered how believing on Jesus produced followers and gathered-churches that—knew instinctively—their possessions were to be held in common for meeting the needs of any and all, literally, house to house. Acts 2:44-45 The ascended Jesus and the outpouring of the Spirit brings about the deliverance and freedom for God's people, thus the call in Isaiah 58 becomes reality. The Isaiah 58 Sabbath rest is a call to restore the intentions behind the original Sabbath commands; this links the presence of God among his people to the flourishing of the City. So it was quite natural for God's people to be like a watered garden, like a spring of water, whose waters do not fail (v. 11b; see why I link the African water crisis to church planting) and you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to dwell in (v. 12b; and can you see why I connect the gospel to the flourishing of our neighborhood). The true mark of keeping Sabbath is to find ways to fulfil the intentions of the command: to find ways to ensure everyone, especially the marginal, oppressed, and the poor—those who lack resources—discover God’s rest and to be included in Sabbath pleasure. What is it about our “Sundays” that ensure others are “ceasing to work” and finding God’s rest . . . ? 1) First, we must ask: what is it about our institutional religion, our way of doing Sabbath that prohibits this? 2) Is our vision of Sabbath and fasting God’s vision or something that places us (places me) in the center? Something for our pleasure? 3) And finally, so, what are we famous for? May our form of church, our form of Sabbath-keeping be such that we ensure that the poor, the homeless, the hungry discover God’s rest and find Sabbath pleasure. For then, we may be called the restorer of the streets.

Idolatry and Poverty: “idolatry comes naturally to us" (samples from a chapter in Wasted Evangelism)6/25/2017  Christian responses to poverty often draw from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5–7; Luke 6), further substantiated by other NT teaching (e.g., Acts 2–4; Jas 1–2). Although important, this tends to be applied more to church-life and to the private sphere rather than developing a response to those living with the effects of poverty. Others turn to the Pentateuch and the Prophets, and, rightly so, for such biblical material is rich in addressing the issues of poverty. The results, however, can tend toward justification for political alignment and socio-economic policies (right/left, conservative/liberal). Christians across the spectrum wrestle with how the Pentateuch and the prophets apply in the (post)modern world. Many question the contemporary relevance of such documents of antiquity addressed to an ancient nation whose social-political location is the Ancient Near East. Nonetheless, there is a way to decipher the significance of OT ethical texts, namely to draw significance from their incorporation into the gospel itself. Mark draws upon a fascinating range of OT contexts throughout his narrative that juxtapose idolatry and the economically vulnerable. Although Mark’s use of the OT is extensive beyond these particular texts, he embeds his Gospel with OT contexts related to the economically vulnerable, whether Law, land-stipulation, or prophetic announcement, which also contain, within the context or flow of thought, mention of idolatry.  The juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty in Exodus and the memory-judgment context in Malachi bear out the apologetic framework discussed above. Additionally, Mark’s constant use of Isaiah also reinforces this framework, which is particularly vivid in Isaiah 40, a component of Mark’s programmatic summary. Mark’s Isaiah referent itself--A voice is calling, “Clear the way for the Lord in the wilderness; make smooth in the desert a highway for our God” (Isa 40:3; Mark 1:3)—carries imagery common to Isaiah’s world, reflecting the procession of ANE monarchs. Here, Yahweh comes as Victor-king, announcing the Good News (v. 9), where all flesh will see the glory of the Lord (v. 5). Isaiah 40 then compares Yahweh to surrounding idolatrous nations, which are like a drop from a bucket (v. 15) and are as nothing before Him . . . less than nothing and meaningless (v. 17; note v. 23). Mark’s introduction contrasts the gospel to the concept of the imperial cult of Caesar linking it with the apologetic of Isaiah, emphasizing the incomparability of Yahweh, whose sovereign power over creation is boasted of (v. 12) and affirmed to be in need of no-one’s counsel regarding justice (vv. 13–14). Yahweh is distinct from the image-bearers made of gold and silver who need to be fashioned by human-hands (vv. 19–20), for he sits above the circle of the earth and stretches out the heavens like a curtain (v. 22). The Holy One takes on all-comers: To whom then will you liken Me that I would be his equal? (v. 25). Isaiah notes the starry hosts (v. 26), each representing idolatrous pagan powers, yet it is Yahweh who created them and calls them by name, indicating his might and strength over the idols of the nations.  Mark’s consistent references to OT material that juxtaposes idolatry and the poor is certainly embedded into the very nature of the gospel, suggesting that the gospel is formative for social arrangements. Mark’s highlighting of these OT texts that juxtapose idolatry and expectations regarding the poor, as well, points to an apologetic and evangelistic potential for social action. Still, moving from ancient text to significance to application can be very difficult, especially as we consider how the application of such texts can include social action outcomes. At the risk of over-generalization, even Christian approaches to poverty tend to align with political views, party affiliations, and social-locations: Politically conservative Christians tend to read capitalism, free markets, and individual charity as biblical solutions to poverty; the politically liberal tend to read more public, state-centered solutions. Although both find some textual support, neither consider the biblical juxtaposition of idolatry and poverty, nor our own human capacity for idolatrous alignments in our own social-locations. L. T. Johnson reminds us that “idolatry comes naturally to us, not only because of the societal symbols and structures we ingest from them, but also because it is the easiest way for our freedom to dispose itself.” Shifting the issue of poverty to the realm of discipleship and apologetics focuses our attention on the social-location of non-poor Christians and their relationship to the poor. In light of the gospel framed by Mark, non-poor Christians should be mindful of the idolatries that can form their own social reality, particularly those experiencing everyday life in places where poverty is not concentrated (i.e., non-urban life). It is not necessarily how OT ethical texts apply to our modern social-location (although important) that is significant, but how the apologetic nature of the idolatry-poverty juxtaposition relates to those who are to be formed by the gospel, then, how that significance dissuades Christians from conforming to any private vs. public dichotomous response to poverty.

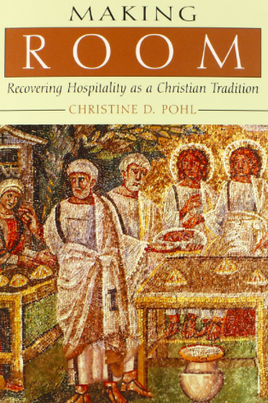

I read books that challenge me, push my convictions, and expose my idolatries. No book, recently, has done this as has Christine Pohl’s Making Room: Recovering Hospitality as a Christian Tradition as I digested page after page. As many who have the patience to read my posts and blogs, I have been rethinking church and its relationship to the poor for some time now. It’s has gotten somewhat more personal as I have been challenged to reevaluate the concept of Christian “hospitality.” Pohl reminds me that biblical hospitality isn’t entertaining friends and family, but the household extending relationships and meeting the needs of the poor and marginal, nearby and traveling through. Typically, most in the church seem to understand hospitality (or the “gift” of hospitality) to be the entertaining or hosting of those we already have some form of relationship (“established bonds”) or shared social status and “significance common ground.” Here, “[h]ospitality builds and reinforces relationships among family, friends, and acquaintances” (13). This kind of hospitality reinforces the shared social status among host and guests, wherein the guests give or affirm something by their presence to the host. Frankly put, this “kind” of hospitality is simply entertaining of guests who affirm or build the host’s social or ecclesiastical status. This is not biblical hospitality. There is commonality, that is the liminal space is shared by hosts and guests before, during, and after the act of hospitality. However, biblical hospitality is more closely related to offering space, comfort, and resources to the stranger, the poor, the marginalized—someone outside or estranged from one’s social status, whereby nothing is gained or affirmed by the hosts. This kind of hospitality, framed by the nature of the gospel itself, is for those disconnected from basic relationships and resources. As Pohl reminds, this “hospitality is central to the meaning of the gospel” (8). Thus, in a real sense,“[h]ospitality is the lens through which we can read and understand much of the gospel, and a practice by which we can welcome Jesus himself” (8). The act of hospitality is a concrete display of the gospel. Prior to hospitality, the host and guests might very well be living out a world that affirms verticality; yet the household becomes a gospel-liminal space that affirms horizontality. This reality—where the gospel is displayed, that is where a leveling of human relationships takes place amid the basic human entity, the household—is an expression of God’s kingdom. Granted biblical hospitality isn’t a mere “how to” for the Christian faith nor should be considered lightly. Yet, I cannot rethink church without considering the Christian tradition of biblical hospitality. It is stretching, convicting, and stressing me to think more deeply. Here is a series of quotes from Making Room that confront me on the issue of being Christian, having resources amid the scarcity of many, and the concept and practice of hospitality. “These hospitality communities embody a decidedly different set of values; their view of possessions and attitudes toward position and work differ from those of the larger culture. They explicitly distance themselves from contemporary emphases on efficiency, measurable results, and bureaucratic organization. Their lives together are intentionally less individualistic, materialistic, and task-driven than most in our society. In allying themselves with needy strangers, they come face-to-face with the limits of a ‘problem-solving’ or a ‘success’ orientation. In situations of severe disability, terminal illness, or overwhelming need, the problem cannot necessarily be ‘solved.’ But practitioners understand the crucial ministry of presence: it may not fix a problem but it solves relationships which open up a new kind of healing and hope” (112). “Recognizing our status as aliens in the world is important for attitudes toward resources and property. Although for most of church history private property was taken for granted, its use among Christians was sometimes moderated by the teaching that everything beyond necessity belonged to the poor. Most of the normative discussions of hospitality assumed that God had loaned property and resources to hosts so they could pass them on to those in need” (114). “In the second-century writing of Hermas we can see an important connection between alien residence and the use of resources. The Similitudes began with the claim that servants of God are living in a ‘strange country,’ far from their true home of heaven. Given their alien status, it makes little sense for believers to collect possessions, fields, or dwellings. Christians live under another law; whatever they have beyond what is sufficient for their needs is for widows, orphans, and other afflicted persons. God gives more than sufficiency for that purpose, not for making believers comfortable and vulnerable to the enticements of a strange land (Sim. 1:1–11)” (115). “If Christians live ‘in a strange land as though in [their] home country,’ they build ‘extraveagent mansions,’ and indulge in ‘countless other luxuries,’ wasting their substance on ‘inanities’ [a nonsensical action, silliness]. Because, when forced to leave the land of their sojourn they will be unable to take their possessions and buildings with them, Christians should instead use their wealth to benefit those in need” (115). Seems that much of our "church" experience affirms our cultural's values regarding social status, continues the horizontal nature of social status quo, and displays the divisions fostered already in society. The way we do church isn't neutral to the issues of poverty, racism, and wealth. Biblical Christian hospitality reverses all of this and helps us to question what we truly believe as Christians concerning our "landed" status as aliens of a different kingdom.

Gary Haugen, President and CEO of International Justice Mission, raises an important point:

Gary points out that for poverty to be eradicated, decreased, or lessened for individuals and communities, everyday violence needs to be addressed first. Good intentions, targeted anti-poverty programs, and crisis services are nice and fill a need, but they will not, ultimately, bring an end to poverty. Building a school in an impoverished global city is a good thing, but it does not good for the young girls who need to walk to school if that walk endangers their lives. As I heard Gary's TED Talk and read his book, The Locust Effect, I could not help but think locally as I serve as a pastor in a very poor community in New Haven, CT, called The Hill. Violence is an everyday threat to good families, adults, teens, and children who are seeking to manage messy, difficult lives in order to have any sense of a good future.

International Justice Mission is an organization that seeks to rescue victims of violence, sexual exploitation, slavery and and protect the poor from violence throughout the developing world.

While attending an early morning men’s prayer and devotional time (as a guest of the one leading the study component), I was horrified by some of the strained thoughts on the passage. The study leader actually tried to stick to the James text; it was the poor rich readers that made comments to lessen the impact of what God was saying through James' words in chapter 5 of his letter. Here are some of my thoughts as the poor rich readers of the Bible commented on James’ words:

Some might not think it, but I was being charitable here. My thoughts were a bit more harsh and even more direct than what I penned above. I will grant that it took me eighteen years after becoming a Christian to begin to see how suburban, affluent, and political I had been reading the Bible--all the while thinking I was interpreting rightly. We need to stop taking the poor out of the texts that actually call us to judgment for not doing something for the poor--neutrality, distance, time, politics will not be allowed as excuses on that day God judges all of our hearts. For on "that day" our riches will have rotten and our garments will have become moth-eaten. Our gold and our silver will have rusted; and their rust, on that day, will be a witness against us and will consume our flesh like fire.

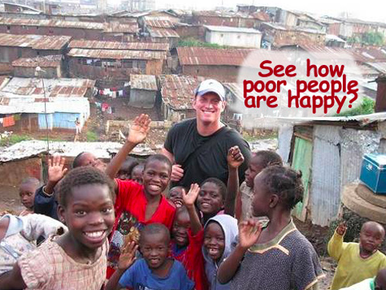

As Christians, we need to ask: does it matter to us that people live in poverty and in conditions that prevent healthy stable, safe lives and a more positive and fruitful future?

Overwhelmed? You should be. Poverty stats stare us right in the face. These stats (and far many more) can be found on almost any poverty website, NGO website, or among the number anti-poverty agency websites here in the USoA or around the globe. A quick Google search will hunt them down for you. What I am most concerned with here, however, is not just simply connecting you with issues of poverty, but that you understand these statistics are not numbers but real, living human beings--our neighbors, locally and globally. One should recall as you are reading these stats what Jesus referred to as the command like unto the first, Love your neighbor as yourself.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed