First, Reread the Mark 3 Commission and Its Components--to Preach and to Cast In order to obey the Mark 3 commission and, thus, show faithfulness to the gospel of God (1:14), we need to think more deeply about the significance of the Mark 3 commission and its application; then, we should seek activities and measurable outcomes that indicate obedience and faithfulness to the gospel. To do this it is necessary to reread the Mark 3 commission more effectively. This will be accomplished by seeking to understand the narrative relationship between the two commissioning components--to preach (v. 14c) and to have authority to cast out the demons (v. 15)—within the “sequence of events emplotted” in Mark’s Gospel.[1] The Mark 3 commission and the fisher-promise—the inaugural connection In chapter 3, “You Will Appear as Fishers,” I demonstrated that the Mark 1:17 fisher-promise finds its inaugural fulfillment in the Mark 3 creation and commission of the twelve (vv. 13–15). Some of those observations and connections bear repeating as we begin to reread the Mark 3 commission. The link between the fisher-promise and the commission can be seen in how Mark introduces the promise (1:17) and, then, how he presents the creation of the twelve (3:13–15):

An obvious promise-fulfillment (I will create/He creates) is crafted into Mark’s narrative regarding the call and creation of the fishers. In Mark 1, the eschatological characters (i.e., Jesus, John the Baptist, the Spirit, and fisher-followers)[3] that play a role in inaugurating the gospel of Jesus Christ are introduced (vv. 4–17). After the mission summary (1:14–15), there is an invitation to become followers (1:17) that includes a promise: “I will make [poieso] you to become fishers of men.” This promise, then, is fulfilled when Jesus creates (epoiesen) the twelve in the Mark 3 commission episode (3:14a). There is a narrative relationship between the call and promise in 1:17 and the summons and commission in 3:13–15, specifically discernible by the repeated use of poieo (create/make), which is often translated appointed, ordained, chose that can mask the reference back to the fisher-promise. The other synoptic Gospel writers did not use poieo (make/create) to characterize the establishment of the twelve, making it more likely that Mark wanted his readers/listeners to make the narrative connection between the fisher-promise (1:17) and its inaugural fulfillment in the commissioning of the twelve (3:14–15). The fisher metaphor and the role of the created twelve indicate that fisher-followers are to be inaugurators of the kingdom (1:17; 3:13–15; 6:7–13)—that is, presenting its demands (1:14–15), expanding (sowing/harvesting) the gospel (4:1–5:43), and imitating Jesus’ ministry (Mark 1:21—6:13). It follows, then, that the content of the commission (vv. 14c–15) is the nature and activity of the created fisher-followers: those who are with Him (v. 14b) are also sent forth to preach and to have authority to cast out the demons (v. 15). At this point, and in light of the Mark 1:17 fisher-promise discussed in chapter 3 (“You Will Appear as Fishers”), the following interpretive summary (I) gives a sense of the meaning of the Mark 3 commission:

[1] Ibid. [2] The author’s translation of Mark 1:17 and Mark 3:13–15. [3] See chapter 3, “You Will Appear as Fishers,” for an elaboration of these characters (from Mark’s introduction) as inaugurators of the kingdom. [4] After each section I present an interpretative summary of the Mark 3 commission in order to show the development of the text’s significance to the reader/listener; as the study expands, the interpretative summary develops.

0 Comments

Authority for application: narrative intention and antecedent authority The process from exegesis to application is characteristically discussed within the context of sermon preparation or homiletics.[1] Typically there is detailed discussion regarding the need to discover the “significance of a text,” that is the time and cultural gaps between the Bible’s historical and cultural settings and the now of the reader/listener. This process is labeled under various titles: contextualization (Osborne), transferring the message (Greidanus), fusion of horizons (Gadamer; Thiselton), and principlization (Kaiser; Virkler).[2] Developing the significance of a text, however, is not simply about seeking the universal truth behind the text and its historical context, or attempting to link the ancient cultural value or historical situation to something similar in the contemporary so it may be “applied.” It should also establish the relationship of the text’s meaning to those in front of the text. Put another way, we need to decipher the significance of the biblical author’s original meaning to the contemporary reader/listener and church community beforedetermining application. Also, simply attaching an “application” to a text, or even a text to an “application,” is not enough; application should be built on reasonable authority.[3] It must produce analogous and relevant obedience reflective of the text. Obedience (i.e., application) ought to correspond in-kind to Mark’s narrative. There needs to be a reasonable association between Mark’s understanding of the gospel and faithful obedience to that gospel. When application is detached and/or dissimilar from his narrative (in this case the Mark 3 commission and his overall Gospel narrative), then there is no authority for that application. In fact, it might not be obedience at all. Application on the contemporary side of the text should find support by analogous associations and applications made by the original author. When application is based on the consequence or result of a text’s meaning, then it carries the weight of biblical authority, which leads to relevant faithful obedience.[4] Abraham Kuruvilla offers a helpful set of principles for developing the significance and range of potential application from a biblical narrative such as Mark’s Gospel. Kuruvilla proposed what he calls “the two rules” for establishing the significance of the text to the readers/listeners, that is, their relationship to the text:1) the Rule of Plot“prepares the interpreter of biblical narrative to attend to the structured sequence of events emplotted in the text, in order to apprehend the world projected by that text” and 2) the Rule of Interaction that “directs the interpreter of biblical narrative to attend to the interpersonal transactions of the characters as represented therein, in order to apprehend the world projected by the text.”[5] Thus, our move here toward application will seek its underlying authority from Mark’s surrounding plot and the role and responsibilities of the characters in the story (i.e., the fisher-followers who are sent forth to preach and to have authority to cast out the demons, 3:14c–15). [1] See Greidanus, Modern Preacher, 157; and, Osborne, Hermeneutical Spiral, 318. [2] Osborne, Hermeneutical Spiral; Greidanus, Modern Preacher; Gadamer, Truth and Method; Thiselton, Two Horizons; Kaiser, Toward an Exegetical Theology; Virkler, Hermeneutics. [3] Kaiser, “Inner Biblical Exegesis,” 33–46. [4] Ibid. [5] Kuruvilla, Text to Praxis, 73. The word “emplot” or “emplotted” is not found in the Oxford English Dictionary or in any dictionary to my knowledge. Kuruvilla, in the context of his “two rules,” refers to “a plot” as “a sequence of causally related events” (Text to Praxis, 73), therefore I take the word and use it here and throughout the chapter to mean em-plotted, or to embed material into a plot; more specifically to assemble together historical events and place them strategically into a narrative in order to create a plot (i.e., a storyline).

Pay Attention to Significance—Think Deeply About Application Walter Kaiser reminds us, “Exegesis is never an end in itself.”[1] In Toward an Exegetical Theology, he rightly points out that the ultimate purpose of exegesis is “never fully realized until it begins to take into account the problems of transferring what has been learned from the text over to the waiting Church.”[2] Obedience to the biblical text is essential to the Christian life and is, as well, defining for the life of the church. This should be the goal of the mindful Christian and what faithful leadership should intentionally foster in a church community (Mark 3:35). This is why developing appropriate, not just “relevant,” application is important. Yet, applying the Bible can offer its own set of problems and difficulties. If we move too quickly to application, it is quite possible to miss the obedience implied by the text (any text for that matter) and, as well, the gospel. Before examining the Mark 3 commission, specifically vv. 14–15, it is worth considering the problem of application. The problem of application In their book, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart point out that many Christians start with “the here and now” and “read into texts meanings that were not originally there.” They rightly affirm that Christians “want to know what the Bible means for us,” and “legitimately so.” However, we cannot make the Bible or the gospel or any text for that matter “mean anything that pleases us and then give the Holy Spirit ‘credit’ for it.”[3] Fee and Stuart hit the mark as it relates to the problem of interpretation: the step of good study and exegesis to decipher the original author’s intention is too often skipped or undertaken lightly, with readers/listeners jumping straight-away to “the here and now.” This actually confuses interpretation with application. Although Fee and Stuart’s point concerns interpretation of the text, the same problem occurs when the “here and now” of contemporary application is read back into the text. We cannot make any application we want from any text, give the Holy Spirit credit, and then call it obedience. Application can often be read into a text, again, confusing interpretation with application. A fixation on the practical does not inevitably lead to obedience of the biblical text. In view of these present set of studies, application, as evangelism is typically understood, might not necessarily indicate faithfulness to the gospel of Jesus Christ (Mark 1:1). This can be a problem with application—that is, application is not always obedience. Moving from meaning to significance, then to application Understanding what the biblical author (in this case, Mark) meant is certainly the first step necessary for seeking faithful obedience to the gospel of Jesus Christ (1:1). The previous five chapters have sought to do just that. Yet, bridging the gap from the then to the now demands thoughtful attention. In order to think more deeply and thoroughly about application, three basic steps are essential to the process:

Meaning is that which is represented by the text, that is, what the biblical author intended by the words, syntactical and contextual relationships, and use of antecedent biblical material and contexts. Significance establishes the relationship between the original meaning and the person, persons, place, or situation (or “anything imaginable”) on this side of the text.[4] The meaning of the text does not change, but its significance to those on this side of the text (who, when, where, etc.) does change and can be relevant in different ways.[5] Application, on the other hand, is the least rigid of the three elements for determining faithfulness to the gospel and can take multiple forms to reflect obedience. Still, application needs to flow from significance and be an appropriate action that reflects the obedience implied by the text (e.g., the Mark 3 commission) or biblical concept (e.g., the gospel). For example, the meaning of the Mark 3 commission is determined by exegesis (an analysis of the text and surrounding narrative). The significance of that meaning is deciphered by the text’s relationship and its implications to those on this side the text. In other words the reader/listener should ask, What is the significance of the Mark 3 commission to me, to my church, and to the community where I live? Application, then, is the appropriate and analogous actions, behaviors, and/or attitudes that produce or indicate faithful obedience to the text. If Mark intended his audience to understand that those who follow after Jesus will be created fishers of men who have a role in inaugurating the kingdom that has arrived in the appearance of God’s Messiah-King (1:1, 14–15, 17),[6] then it is important to discern the significance of the commission components to preach and to have authority to cast out the demons (3:14–15) for today’s readers/listeners. Application, then, requires a determination of what appropriate and analogous actions correspond to thatsignificance. [1] Kaiser, Toward an Exegetical Theology, 149. [2] Ibid. [3] Fee and Stuart, How to Read the Bible, 26. [4] Hirsch, Validity in Interpretation, 8. [5] Ibid., 255. [6] See chapter 3, “You will Appear as Fishers,” for the background of this interpretation.

And he appointed twelve (whom he also named apostles) so that they might be with him and he might send them out to preach and have authority to cast out demons (Mark 3:14-15).

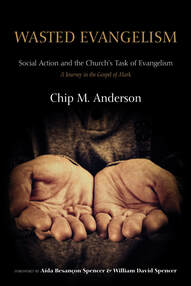

“You need to be more practical.” These are the dreaded words no preacher or Bible teacher wants to hear, particularly if he or she wants to be considered effective and well-liked in modern, contemporary church circles. I am among the unfortunate who have been admonished and, even, scolded with these words more often than I’d like to admit. Yet, I am not ready to yield to the tyranny of the practical. As modern Christians, particularly evangelicals, we often measure biblical information (teaching, preaching, sermons, commentary, Bible studies, etc.) by its immediate practical value. The up-side—Christians want to be obedient to Scripture. This is a good thing. The down-side—a preoccupation with the “practical” can too often dissuade us from thinking deeply about the significance of a text, the kind of reflection needed for developing well-thought through application, which ought to be based on an appropriate and authoritative reading (i.e., an exegesis) of the text. The path to application can be too quickly made and too frequently unconnected to the original intention of the biblical author. Wasted Evangelism is not intended to be “practical.” However, I have worked hard throughout the last five chapters to uncover the meaning of the Markan texts under consideration, ending each study with the significance of these texts for church communities, for church leaders, and for those who call themselves Christian. Each chapter unfolded more fully the nature and content of the gospel we are to believe (Mark 1:1, 14–15), seeking to answer the question, How should my faith, our church, our discipleship, our evangelism be informed and formed by the narrative of Mark’s Gospel? I mentioned early in this book that chapters 1 through 5 were originally papers presented at meetings of the Evangelical Theological Society between 2006 and 2012.[1] At the conclusion of my paper on the Mark 1:17 “fishers of men” text (chapter 3 in this volume), I made this assertion: The fisher metaphor is appropriate, not just narrowly for individual, private salvation, but more broadly for applications, activities, and outcomes of social action and justice, as well. I offered this deduction based on the antecedent OT meaning of the fisher concept and on my conclusion that the Mark 3 commission (vv. 13–15)[2] was the inaugural fulfillment of the Mark 1:17 promise that Jesus would create his followers to become fishers of men. After I finished presenting the paper, during the Q&A, a very nice gentleman (a pastor I believe) asked a reasonable follow-up question: “Does that mean ‘casting out demons’ is social action?” Without hesitation I responded, “Yes, it does.” As a result of my overly confident off-the-cuff response, I began crafting a longer answer. This chapter, in part, is that longer answer: In light of the promise to be created fishers, what is the significance of the Mark 3 commission for Christians and church communities on this side of the text? This final chapter is a far cry from any “how to” regarding specific, practical application. Although there is a measure of exegetical investigation regarding the Mark 3 commission, this chapter, more so, offers a model for deciphering the significance of the text. Here, I will focus on the process for developing application that reflects obedience to the text and a legitimate range of potential outcomes, which I posit can be related to social action that addresses the issues of poverty that surround local congregations. This will be as practical as I get! The Gospel, Deep Enough to Include God’s Concern for the PoorThe previous five chapters have been a series of in-depth exegetical arguments, demonstrating that Mark’s programmatic content links the gospel and evangelism to social action.[3] Thus, social action falls legitimately within the realm of evangelism. I have endeavored to show that a narrow, proclamation-centered definition of evangelism based exclusively on word-studies and isolated proof-texts does not match the narrative meaning of the gospel, particularly as Mark presents the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God (1:1). Clearly a mere verbal- and cognitive-based definition of evangelism solely related to the etymology of the word “evangelize” is too narrow and devoid of much of the biblical content that Mark gives his Gospel narrative. As the previous studies have shown, Mark relies on OT backgrounds and contexts (e.g., 1:2–3) to fill the gospel of Jesus Christ (1:1) with defining and programmatic content. Typically, it is accepted that the gospel is defined by incorporating various OT motifs and concepts such as God’s dominion, the Exodus, exile, redemption, and even sacrificial propitiation and forgiveness. The previous chapters have shown that the same OT contexts that Mark harnesses to give programmatic definition to the gospel also clearly contain correspondences and direct references regarding socio-economic relationships and community responsibilities toward the economically vulnerable and the poor.[4] As the five previous studies have demonstrated, social action, therefore, can be evangelism. In chapter 3, “You Will Appear as Fishers,” an examination of Mark 1:17, I concluded that the promise to be created “fishers of men” finds its inaugural fulfillment and premiere “application” in the Mark 3 commission; namely, fishers are those who are with Jesus and who, then, will be sent out to preach and to have authority to cast out the demons. Through the Markan context and antecedent OT background, I showed that the “fisher metaphor is appropriate for applications, activities, and outcomes of social action and justice”([x-ref]).[3] This implies that the Mark 3 commission to preach (v. 14c) and to have authority to cast out the demons (v. 15) can be associated with social action and, thus, can be legitimate obedience to Jesus-Messiah and faithful application of the gospel. Close examinations of Mark’s programmatic understanding of the gospel of Jesus Christ (1:1–3), the fisher-promise (1:17), the Mark 3 sandwich and Beelzebul episode (3:20–35), the Mark 4 parable of the Sower who Sows, and the account of the widow vs. duplicitous scribes in Mark 12 all have shown that the gospel itself is defined broadly and deeply enough to include God’s concern for the poor. Fisher-followers of Jesus, the Messiah-King (1:1, 17), are commissioned to demonstrate the presence of God’s kingdom (3:14–15), which is the gospel of God (1:14–15). As part of the application process (that is, thinking deeply and more thoroughly about application), the following seeks to show that the significance of “preaching” and “casting” (3:14–15) provides a basis for building social action outcomes into a church’s evangelistic activities. [1] This chapter was originally, in part, presented at the annual meeting of the Northeast Region of the Evangelical Theological Society, which met at the Alliance Theological School, Nyack, NY, April 2013. [2] The full text encompasses vv. 13–19, which includes the list of the twelve in vv. 16–19; however this study more specifically will focus on vv. 14–15, the Mark 3 commission component. [2] My working definition for biblical social action: a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor (see the Introduction for an extended explanation). [3] All the previous studies/chapters in this volume address the wide range of OT texts related to the poor; see chapter 5, “Idolatry and Poverty,” specifically for a list of OT texts and contexts Mark utilizes in his Gospel which refer to the economically vulnerable and issues of justice. [4] See chapter 3, “You will Appear as Fishers” for the full exegetical argument.

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed