I read books that challenge me, push my convictions, and expose my idolatries. No book, recently, has done this as has Christine Pohl’s Making Room: Recovering Hospitality as a Christian Tradition as I digested page after page. As many who have the patience to read my posts and blogs, I have been rethinking church and its relationship to the poor for some time now. It’s has gotten somewhat more personal as I have been challenged to reevaluate the concept of Christian “hospitality.” Pohl reminds me that biblical hospitality isn’t entertaining friends and family, but the household extending relationships and meeting the needs of the poor and marginal, nearby and traveling through. Typically, most in the church seem to understand hospitality (or the “gift” of hospitality) to be the entertaining or hosting of those we already have some form of relationship (“established bonds”) or shared social status and “significance common ground.” Here, “[h]ospitality builds and reinforces relationships among family, friends, and acquaintances” (13). This kind of hospitality reinforces the shared social status among host and guests, wherein the guests give or affirm something by their presence to the host. Frankly put, this “kind” of hospitality is simply entertaining of guests who affirm or build the host’s social or ecclesiastical status. This is not biblical hospitality. There is commonality, that is the liminal space is shared by hosts and guests before, during, and after the act of hospitality. However, biblical hospitality is more closely related to offering space, comfort, and resources to the stranger, the poor, the marginalized—someone outside or estranged from one’s social status, whereby nothing is gained or affirmed by the hosts. This kind of hospitality, framed by the nature of the gospel itself, is for those disconnected from basic relationships and resources. As Pohl reminds, this “hospitality is central to the meaning of the gospel” (8). Thus, in a real sense,“[h]ospitality is the lens through which we can read and understand much of the gospel, and a practice by which we can welcome Jesus himself” (8). The act of hospitality is a concrete display of the gospel. Prior to hospitality, the host and guests might very well be living out a world that affirms verticality; yet the household becomes a gospel-liminal space that affirms horizontality. This reality—where the gospel is displayed, that is where a leveling of human relationships takes place amid the basic human entity, the household—is an expression of God’s kingdom. Granted biblical hospitality isn’t a mere “how to” for the Christian faith nor should be considered lightly. Yet, I cannot rethink church without considering the Christian tradition of biblical hospitality. It is stretching, convicting, and stressing me to think more deeply. Here is a series of quotes from Making Room that confront me on the issue of being Christian, having resources amid the scarcity of many, and the concept and practice of hospitality. “These hospitality communities embody a decidedly different set of values; their view of possessions and attitudes toward position and work differ from those of the larger culture. They explicitly distance themselves from contemporary emphases on efficiency, measurable results, and bureaucratic organization. Their lives together are intentionally less individualistic, materialistic, and task-driven than most in our society. In allying themselves with needy strangers, they come face-to-face with the limits of a ‘problem-solving’ or a ‘success’ orientation. In situations of severe disability, terminal illness, or overwhelming need, the problem cannot necessarily be ‘solved.’ But practitioners understand the crucial ministry of presence: it may not fix a problem but it solves relationships which open up a new kind of healing and hope” (112). “Recognizing our status as aliens in the world is important for attitudes toward resources and property. Although for most of church history private property was taken for granted, its use among Christians was sometimes moderated by the teaching that everything beyond necessity belonged to the poor. Most of the normative discussions of hospitality assumed that God had loaned property and resources to hosts so they could pass them on to those in need” (114). “In the second-century writing of Hermas we can see an important connection between alien residence and the use of resources. The Similitudes began with the claim that servants of God are living in a ‘strange country,’ far from their true home of heaven. Given their alien status, it makes little sense for believers to collect possessions, fields, or dwellings. Christians live under another law; whatever they have beyond what is sufficient for their needs is for widows, orphans, and other afflicted persons. God gives more than sufficiency for that purpose, not for making believers comfortable and vulnerable to the enticements of a strange land (Sim. 1:1–11)” (115). “If Christians live ‘in a strange land as though in [their] home country,’ they build ‘extraveagent mansions,’ and indulge in ‘countless other luxuries,’ wasting their substance on ‘inanities’ [a nonsensical action, silliness]. Because, when forced to leave the land of their sojourn they will be unable to take their possessions and buildings with them, Christians should instead use their wealth to benefit those in need” (115). Seems that much of our "church" experience affirms our cultural's values regarding social status, continues the horizontal nature of social status quo, and displays the divisions fostered already in society. The way we do church isn't neutral to the issues of poverty, racism, and wealth. Biblical Christian hospitality reverses all of this and helps us to question what we truly believe as Christians concerning our "landed" status as aliens of a different kingdom.

0 Comments

*This is the fourth instalment of quotes from my presentation on "Church (local), the poor and their neighborhood," which are somewhat random, but still focused on the church and the poor. For all the posted "Church (local) quotes >>

A hard, maybe even harsh, but a true and needed word for God’s people, for those who are questioning the darkness, confusion, uncertainty, and chaos that surrounds them; a word for those called to the humble but selfless mission to save others no matter the cost to themselves . . from Samwise Gamgee . . .

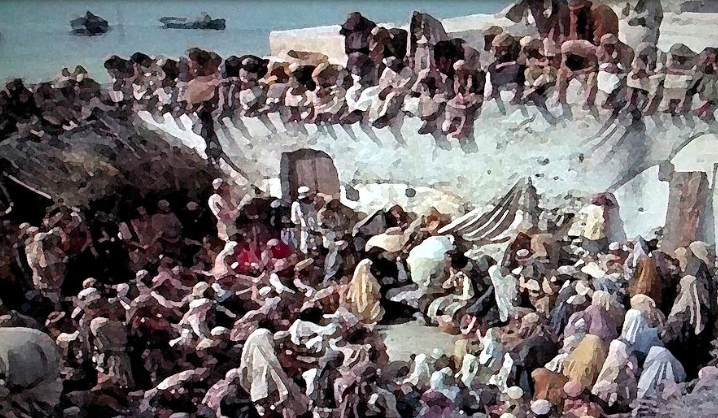

Each spring I attempt to write a brief paper for our Northeast Regional Evangelical Theological Society. This year (2016) I thought I’d put together a study on the Synoptic writers’ use of “crowd” (oxlos) in their Gospel narratives. Below is my paper submission abstract and outline, along with a brief reflection on how I came to consider “crowd” as a Gospel character. A Real Time, Messy Missional (Local) Church: What “Crowd” as a Gospel Character Teaches About Being Missional-Church Pastors and lay-teachers tend to be more comfortable focusing on cognitive effects and propositional aspects of the gospels like Jesus’ preaching, parables, and teaching. Characters are another matter in the gospel narratives, for they are more likely to be “identified with” or used as “lessons” in which they tend to be allegorized, devotionalize, or typified rather than seeking how they are used in the story and, thus, developed for their contextual interpretive significance. The “crowd,” on the other hand, is rarely viewed as a character in the Synoptic Gospels and, thus, often not considered for its interpretive value. The “crowd” character presents a difficulty for the interpreter of the Gospel narratives. The “crowd” is that messy, unclear presence at much of Jesus’ ministry—sometimes for Jesus, sometimes against him, occasionally believing, oftentimes unbelieving, and, then, more so, it is split believing and not believing. And what makes the interpretation-application process even more troublesome, often the reader is left just not knowing the crowd’s confessional state of mind. One thing is consistent, however, the “crowd” is almost always present at Jesus’ public activities, teaching, and travels. Conversely, one could posit that Jesus was present among the crowd in much of the Synoptic Gospel narrative. Assuming that the Gospels were written to help local, believing communities to imagine how the gospel was to inform and form their discipleship and missional purpose, the “crowd” has value at the teaching level. What does the Synoptic Gospel crowd reveal about a church’s mission and presence among others? Is our building-centered church experience prohibitive of such crowds? What can the significance of the Synoptic Gospel crowd (as) character tell or instruct us on how we should do church, today? To give this a contemporary social location, the forming significance of “crowd” as a Synoptic Gospel character should be juxtaposed with the forming power of a building-centered church experience and how this affects the missional life of the local church. We should grasp how a building-centered church experience is anti-crowd; the “crowd” as a Gospel character should inform our exegetical-significance-application process; we should observe how the role of “crowd” and its impact in the text informs the missional purpose of a local church; and, the significance of “crowd” shows is what is suitable “space” for a local church. This effort here [in the full paper] seeks to demonstrate (conclude) that a missional-church creates space for crowd to engage the gospel of the kingdom. A preliminary reflection on “crowd  After studying and writing on the Mark 3 Beelzebul passage and “the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit” (it isn’t what you think it is; trust me), I was fascinated by Mark’s use of “crowd” throughout his Gospel. If we take Mark as inspired and his use of “crowd” as a strategic character in the gospel story, it seems to me, we should grasp the crowd’s significance within our understanding of both the gospel and, as well, the (local) church. Obviously more needs to be studied and written on this, but a brief forethought on crowd is worth it as we strive to rethink church. One specific characteristic of the “crowd” worth noting, it is always around Jesus (or Jesus is in the midst of the crowd), meeting and greeting him, listening to him, and sometimes literally jumping over one another to be near to what Jesus was doing or saying. Second, another aspect to grasp, the “crowd” is sometimes believing and sometimes unbelieving, and sometimes, well, you just can’t tell one way or another. Sometimes the “crowd” is even split by belief and unbelief. Yet, the presence of Jesus was marked by the presence of "crowd" (ochlos).  I have come to the conclusion this is the way it should be with the (local) church, which is God’s fullness, Christ’s body local (e.g., Ephesians 1:22). Seriously, as the body of Jesus, the church, that is, a local church, should be surrounded by “crowd” in a similar fashion as Jesus himself was surrounded by “crowd.” We read out such inferences (to “crowd”) in the Gospels and mostly cannot conceive the church’s role in this way. This is one of the negative aspects of our building-centered church habits. We need to stop thinking church as a building, and acting like it is—in fact, a building-centered church experience is prohibitive of this crowd-missional aspect of the church's purpose and, can be, antithetical of gospel. We, as evangelicals, are uncomfortable with crowds “at” church; uncomfortable where the categories of believing and unbelieving are rather foggy. (This does havoc on a high fencing view of communion, for sure.) This suggests we need to rethink church and where “church” (and possibly how it) happens. Whereas the inner circle of followers and disciples (we more comfortably refer to as the church members or regulars attenders) are believing (and sometimes maybe even struggling to believe) and, at differing levels, learning obedience, on the other hand, the outer circle that surrounds the church (and sometimes crowding inside as it were) is a little foggy on the issue of belief. But, they ought to be there—sometimes they’ll look like believers, sometimes they won’t, and sometimes you just will not be able to tell one way or another. We need to see “crowd” around the (local) church as a vital character in the (local) church’s story within the community it seeks to minister and serve. Perhaps more biblically accurate, we should experience church in the midst of “crowd,” for the church is Jesus’ body--and this is what Jesus displayed in the Gospel narratives.  I am in favor of and an advocate for a public social service net--I worked hard at and made my livelihood from one for many years. I have designed and facilitated many programs on behalf of our most vulnerable. While still a good thing, I am very weary of a government-run and semi-government (by design which receive substations government funds either by the grant process of by legislation (or law) non-profit system (yes, they are one system) whose programs still leave the poor in poverty with little or no escape (no upward mobility, if you will) and, in the end, that mostly benefits the politicians and EDs/CEOs who are dependent on the poor, well, being poor for their votes and grant money, and, as well, the massive bureaucracies--the armies of clerical and professional poverty-fighters whose livelihoods and their own upward mobility are only secure in as much as poverty continues. The least likely beneficiary for such a system is the actual poor. In fact, too many people and groups are dependent on the poor remaining poor. I have a problem with this. It is time to rethink how poverty is addressed.  Even large corporations—the biggest ones—aren't geared to support a truly anti-poverty approach to, well, end poverty and/or move the poor out of poverty. Year ago now, I had asked one of the most involved funders of poverty programs (GE, Inc.) if they'd consider a new approach to fighting poverty, one that will actually move individuals and families OUT of INTERGENERATIONAL POVERTY and the response: "Sorry, we can't. That's just not one of our buckets." Yes, indeed, all players need to be at the table (including BIG BUSINESS and the GOVERNMENT), yet I believe the church, or better, churches (implying churches local) are the ones to offer a new (really an older) paradigm for fighting poverty. But, in order to be able to and best be positioned to alleviate poverty and actually move people (really communities) out of poverty, the church needs to rethink church, which in the end might be the harder system to undo.

There is some irony to the two typical reactions (that is, the two interpretations) to the story, which I call the poor widow vs. duplicitous scribes episode: one holds it up as an example of faithful devotion and sacrificial giving, while the other sees judgment, lament, and tragedy. Everything about this short story, in Mark 12, suggests that the widow is being taken advantage of by a temple leadership that does not have her best interests in mind. Although it might be advantageous for churches and Christian ministries to see the poor widow as an example of sacrificial giving, this interpretation, however, turns the text 180 degrees contrary to its context and is disconnected from the plot Mark has developed through his Gospel narrative. This leads to a failure of interpretation that distracts the Christian community from developing biblically authoritative and analogous application from this text. This episode fits within Mark’s paradigm for Christian discipleship; but, what does it require of the Christian community? How does it inform the Christian call to discipleship? Is the widow the focal point, or is the failure of temple leadership the crux of the story that should form the church’s understanding of discipleship? Mark does draw a narrative correspondence between the widow giving her whole life [my translation for holon ton bion autēs, 12: 44c] and Jesus’ imminent sacrifice, the giving of his own life. Some take this to mean that “we, too, should give our lives and resources sacrificially like the widow and Jesus.” No! This is an inappropriate analogy and is an ill-fitted correspondence to the text and its context. While the link to Jesus is certainly there in the Gospel story, the larger issue is the burden that was improperly, even maliciously, laid on the poor widow by the temple establishment—the poor widow should not have had to give her whole life (v. 44c). This is the point here: as God’s representatives, the scribes and, as well, the whole of temple leadership should have been her advocates, not the cause of her destitution. The link to Jesus is simply that he will step up to be her advocate and will give his life on her behalf.

Jesus’ observation of a poor widow who had given the last of her financial resources for which her whole life depended can just as equally be read as “downright disapproval” [Addison Wright] and not as praise. The contrast between the scribes and the widow is not about piety, but for illustrating and emphasizing the duplicitous conduct of the scribes. It is lamentable to watch this act of the poor widow in the presence of such wealth and religious duplicity. We can fail to notice there is a tragedy happening that day, right there in the temple courts. *From “Widows in Our Courts (Mark 12:38–44): The Public Advocacy Role of Local Congregations as Discipleship,” chapter 1 of Wasted Evangelism. All royalties from sales of Wasted Evangelism is given to support our church planting efforts and ministry in The Hill community of New Haven, CT.

The basic dictionary definition of social action is “individual or group behavior that involves interaction with other individuals or groups, especially organized action toward social reform.”[1] Within the discipline of sociology the concept is associated with the work of Max Weber, who understood social action in terms of the relationships people have between social structures and the individuals whose actions create them.[2] Acadia University professor Peter Horvath defines social action as “participation in social issues to influence their outcome for the benefit of people and the community” and concludes that “[s]ocial action can, under favorable circumstances, produce actual empowerment, impact, or social change.”[3] Horvath underscores the importance of seeking and implementing necessary change on behalf of others who do not have access to power for needed change. This can be seen within the social service and welfare arena in which the term “social action” is often used simply to mean efforts to improve social conditions or to address the needs of a particular group within a social setting or societal structure. Social action can be understood as attempts to improve human welfare and to develop commitment to each other, advocating for and/or making changes in social structures (whether at the individual, community, or legislative levels) for the betterment of all. Social action, therefore, is principally the means by which one group offers alterative means to an end for another group, taking action or advocating for action to address social issues and community life. Within the context of poverty, social action is not merely charity, alms-giving, or the transfer of wealth. It is actions taken to address relationships between the poor and the non-poor and, as well, the relationship between the poor, the social structures that can cause or promote poverty, and individuals or groups whose actions create those social structures. Social action is, therefore, associated with actions taken by individuals or groups on behalf of others, in particular advocating on behalf of marginalized or powerless individuals or groups whose access to the systems of power are limited or nonexistent.[4] What, then, is evangelistic social action? Throughout the studies in Wasted Evangelism, I frequently reference Mark’s programmatic[5] use of OT contexts regarding the economically vulnerable and the land, particularly contexts that reference Exodus land-laws (e.g., Exod 21–23; Mal 3:1–5; Jer 5:2; 7:9; Amos 4:1–2; etc.), which, for Mark, informs his understanding of the gospel (Mark 1:1–3; note Exod 23:20; Mal 3:1). The Exodus land-laws are operating behind his programmatic theme, informing the reader/listener of the gospel’s content (i.e., what the gospel is and what it means). Land-laws were given to ensure that the economically vulnerable (i.e., the land-less) were full participants in the benefits of living in the land.[6] This supports the importance of considering the poor in relationship to the Christian community’s social context. In light of Mark’s association of the kingdom with the gospel (1:14–15) and the gospel’s programmatic association with the Exodus land-laws, I propose that biblical social action is a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor.[7] Stephen Mott, former Professor of Christian Social Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, points out that the Bible speaks of what is called “social action” in terms of carrying out justice and caring for the needs of the weak. In her book, Social Justice Handbook, Mae Cannon affirms a similar understanding of the biblical concept of social justice: The resources that God provides were made available to his people from the very beginning. Justice is expressed when God’s resources are made available to all humans, which is what God intended. Biblical justice is the scriptural mandate to manifest the kingdom of God on earth by making God’s blessings available to all.[8] As my Wasted Evangelism, that is, the six deep, exegetical studies (i.e., the chapters), affirm, social action is a relevant and legitimate evangelistic activity when it promotes actions and outcomes that demonstrate the inaugural presence of God’s rule and reign over creation. Thus, social action, the advocacy and activities on behalf of the economically vulnerable, should be an intentional component of a church’s task of evangelism. A slightly adapted set of paragraphs from my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism. All royalties received from sales of Wasted Evangelism go to support our church plant in The Hill community of New Haven, CT. Further Wasted Blog on Barriers to discussing biblical, evangelistic social action >> Barriers [1] Social action. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/social action (accessed: May 27, 2013).

[2] Weber, Economy and Society, 1:78; also see Weber’s Theory of Social and Economic Organization for an in-depth understanding of his social theory, which includes his view of social action. [3] Horvath, “ Organization of Social Action,” 221–31; also see Townley et al.,“Performance Measures,” 1045–72. [4] What is being advocated for throughout [my] six studies is biblical social action that addresses the needs of economically vulnerable individuals and families and activities that seek to reduce the causes of poverty. Although [Wasted Evangelism] does not intend to endorse any particular method or specific type of activity for evangelistic social action, I feel compelled to stress the importance of community development models over paternalistic methods of charity or wealth distribution. I am grateful to Doran Wright, pastor of Grace City Church Bridgeport (CT), for recommending to me A Heart for the Community: New Models for Urban and Suburban Ministry (John Fuder and Noel Castellanos, eds.) as a text that underscores the importance of Christian community development for addressing the needs of poor neighborhoods and communities. Also, see Lupton’s Toxic Charity. For a catalog of various social action and anti-poverty related ministries see Mae Elise Cannon’s Social Justice Handbook. [5] By “programmatic” I mean that a concept, phrase, or an event described in the text contains a main theme of Mark’s Gospel, which offers a referent for meaning, definition, and/or content (an internal hermeneutical orientation) that Mark sets forth, assisting his audience to understand more clearly the parts or plotline of the story in view of the whole story. [6] See Brueggemann’s The Land regarding the biblical responsibilities of God’s people to the land and to the land-less (i.e., the economically vulnerable and the poor). [7] See chapter 2, “Wasted Evangelism.” [8] Cannon, Social Justice Handbook, 22. The goal or objective I have for this WastedEvangelism blog is to present my thoughts and commentary on the issues of poverty, the poor, church, church growth, discipleship, and, of course, evangelism. I believe we need to rethink these topics through better readings of the Bible and more honest reflection (at I try to be honest) on the issues of poverty, the poor and the marginal, oppression, and justice. My top two posts for 2016, which generated the most visits to my Wasted Evangelism site, were:

The runner up, 3rd most visited in 2016, was a set of quotes I gathered and posted from a presentation I did on “Church, the poor and their neighborhood”: My first post of 2017, on January 1, broke all previous WastedEvangelism blog posts to date. A great way to start the new year. The January post, garnishing the all-time highest record of visits is: I will try better and more consistently to post throughout the week during 2017. Thanks for visiting and reading my marginal thoughts. Here's to hoping you will be joining me regulary to rethink Church, the poor, poverty, and evangelism. PS I am a church planter and pastor of Christ Presbyterian Church in The Hill and a flawed practitioner of Wasted Evangelism. I am learning about Wasted Evangelism, myself, through my experience in The Hill and through the good people of CPC in The Hill. The picture at the head of this post is a night-time shot of the neighborhood, just outside our place of worship in The Hill. Check out the three books that most influenced me this past year >>

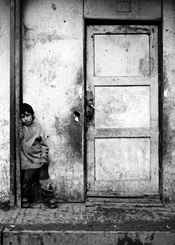

An article, “To the Poor, Poverty is More Than Material,” posted on the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics's website lifted an excerpt from a multiauthor volume called For the Least of These: A Biblical Answer to Poverty. The lengthy quote comes from Peter Greer's essay, “A Call to Compassionately Move Beyond Charity.” I was impressed by the reflection on how the poor view themselves and it reminded me of Matthew's “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (5:3). So many take Matthew's reference more broadly to mean those who have a good attitutde and recognize their “poverty” before God. You know, individuals who are humble and not arrogant. These interpretors make a difference between Luke's simple “Blessed are you who are poor" (6:20) and Matthew's “poor in spirit.” However, this is a rationalized, poor rich reading of Scripture that basically strips the poor out of “poor in spirit.” The excerpt from Peter Greer's essay gives us a basis for understanding that living in poverty is more than just a material matter and reminds us that the poor are indeed poor in spirit. In the 1990s, World Bank surveyed over sixty thousand of the financially poor throughout the developing world and how they described poverty. The poor did not focus on their material need; rather, they alluded to social and psychological aspects of poverty. Analyzing the study, Brian Fikkert and Steve Corbett of the Chalmers Center for Economic Development said, “Poor people typically talk in terms of shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, and voicelessness.” The study highlights that, by nature, poverty is innately social and psychological . . . In my book, Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, my definition of “social action” takes into consideration that those living with the effects of poverty are subject to systems and structures, that is the powers, that make poverty more than just material. Social action, therefore, is principally the means by which one group offers alterative means to an end for another group, taking action or advocating for action to address social issues and community life. Within the context of poverty, social action is not merely charity, alms-giving, or the transfer of wealth. It is actions taken to address relationships between the poor and the non-poor and, as well, the relationship between the poor, the social structures that can cause or promote poverty, and individuals or groups whose actions create those social structures. Social action is, therefore, associated with actions taken by individuals or groups on behalf of others, in particular advocating on behalf of marginalized or powerless individuals or groups whose access to the systems of power are limited or nonexistent. We must understanding that being poor is more than the lack of something material, but is living with the effects of poverty upon the whole person. This will help temper our judgments about the poor and why they are poor—and perhaps move us as Christians to relocate ourselves into the lives of the poor. This way we will experience and recognize what it is to be “poor in spirit.” Then, we might very will gain insight and appreciate why Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3).

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed