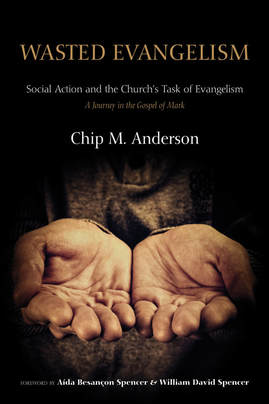

Almost all works on the relationship between evangelism and social action, most books on the church and the poor, and every book out there on the subject of Christians and social justice are argued from experience, a theological bent, a political aisle, or a church experience. Although such platforms have value and have their place, there are few, if any, volumes that seek an exegetical foundation for the author’s conclusion: a what does the text imply? My Wasted Evangelism is an exegetical argument for understanding that social action can be a component of biblical evangelism and ought to be an element in a church’s task of evangelism.

Please consider purchasing a copy of my Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism, a deep, exegetical read into the Gospel of Mark. All royalties go to support our church planting in the Hill community of New Haven, CT. The book and its e-formats can be found on Amazon, Barns'n Noble (and most other online book distributors) or directly through the publisher, Wipf & Stock directly. Here are some excepts from each of the chapters: Samples

0 Comments

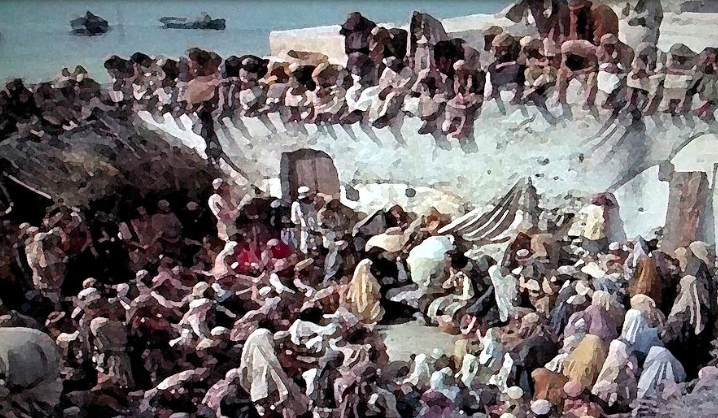

Each spring I attempt to write a brief paper for our Northeast Regional Evangelical Theological Society. This year (2016) I thought I’d put together a study on the Synoptic writers’ use of “crowd” (oxlos) in their Gospel narratives. Below is my paper submission abstract and outline, along with a brief reflection on how I came to consider “crowd” as a Gospel character. A Real Time, Messy Missional (Local) Church: What “Crowd” as a Gospel Character Teaches About Being Missional-Church Pastors and lay-teachers tend to be more comfortable focusing on cognitive effects and propositional aspects of the gospels like Jesus’ preaching, parables, and teaching. Characters are another matter in the gospel narratives, for they are more likely to be “identified with” or used as “lessons” in which they tend to be allegorized, devotionalize, or typified rather than seeking how they are used in the story and, thus, developed for their contextual interpretive significance. The “crowd,” on the other hand, is rarely viewed as a character in the Synoptic Gospels and, thus, often not considered for its interpretive value. The “crowd” character presents a difficulty for the interpreter of the Gospel narratives. The “crowd” is that messy, unclear presence at much of Jesus’ ministry—sometimes for Jesus, sometimes against him, occasionally believing, oftentimes unbelieving, and, then, more so, it is split believing and not believing. And what makes the interpretation-application process even more troublesome, often the reader is left just not knowing the crowd’s confessional state of mind. One thing is consistent, however, the “crowd” is almost always present at Jesus’ public activities, teaching, and travels. Conversely, one could posit that Jesus was present among the crowd in much of the Synoptic Gospel narrative. Assuming that the Gospels were written to help local, believing communities to imagine how the gospel was to inform and form their discipleship and missional purpose, the “crowd” has value at the teaching level. What does the Synoptic Gospel crowd reveal about a church’s mission and presence among others? Is our building-centered church experience prohibitive of such crowds? What can the significance of the Synoptic Gospel crowd (as) character tell or instruct us on how we should do church, today? To give this a contemporary social location, the forming significance of “crowd” as a Synoptic Gospel character should be juxtaposed with the forming power of a building-centered church experience and how this affects the missional life of the local church. We should grasp how a building-centered church experience is anti-crowd; the “crowd” as a Gospel character should inform our exegetical-significance-application process; we should observe how the role of “crowd” and its impact in the text informs the missional purpose of a local church; and, the significance of “crowd” shows is what is suitable “space” for a local church. This effort here [in the full paper] seeks to demonstrate (conclude) that a missional-church creates space for crowd to engage the gospel of the kingdom. A preliminary reflection on “crowd  After studying and writing on the Mark 3 Beelzebul passage and “the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit” (it isn’t what you think it is; trust me), I was fascinated by Mark’s use of “crowd” throughout his Gospel. If we take Mark as inspired and his use of “crowd” as a strategic character in the gospel story, it seems to me, we should grasp the crowd’s significance within our understanding of both the gospel and, as well, the (local) church. Obviously more needs to be studied and written on this, but a brief forethought on crowd is worth it as we strive to rethink church. One specific characteristic of the “crowd” worth noting, it is always around Jesus (or Jesus is in the midst of the crowd), meeting and greeting him, listening to him, and sometimes literally jumping over one another to be near to what Jesus was doing or saying. Second, another aspect to grasp, the “crowd” is sometimes believing and sometimes unbelieving, and sometimes, well, you just can’t tell one way or another. Sometimes the “crowd” is even split by belief and unbelief. Yet, the presence of Jesus was marked by the presence of "crowd" (ochlos).  I have come to the conclusion this is the way it should be with the (local) church, which is God’s fullness, Christ’s body local (e.g., Ephesians 1:22). Seriously, as the body of Jesus, the church, that is, a local church, should be surrounded by “crowd” in a similar fashion as Jesus himself was surrounded by “crowd.” We read out such inferences (to “crowd”) in the Gospels and mostly cannot conceive the church’s role in this way. This is one of the negative aspects of our building-centered church habits. We need to stop thinking church as a building, and acting like it is—in fact, a building-centered church experience is prohibitive of this crowd-missional aspect of the church's purpose and, can be, antithetical of gospel. We, as evangelicals, are uncomfortable with crowds “at” church; uncomfortable where the categories of believing and unbelieving are rather foggy. (This does havoc on a high fencing view of communion, for sure.) This suggests we need to rethink church and where “church” (and possibly how it) happens. Whereas the inner circle of followers and disciples (we more comfortably refer to as the church members or regulars attenders) are believing (and sometimes maybe even struggling to believe) and, at differing levels, learning obedience, on the other hand, the outer circle that surrounds the church (and sometimes crowding inside as it were) is a little foggy on the issue of belief. But, they ought to be there—sometimes they’ll look like believers, sometimes they won’t, and sometimes you just will not be able to tell one way or another. We need to see “crowd” around the (local) church as a vital character in the (local) church’s story within the community it seeks to minister and serve. Perhaps more biblically accurate, we should experience church in the midst of “crowd,” for the church is Jesus’ body--and this is what Jesus displayed in the Gospel narratives.  It is understandable that suburban, exurban, and affluent church congregations, typically, do not see the link between the gospel and the flourishing of their neighborhood. Here’s the problem: Which neighborhood? Whose neighborhood? And, O by the way, our neighborhoods by definition are flourishing. Suburban and exurban congregations tend to be a mix of like-minded, demographically related, geographically similar people who travel various distances away from their own neighborhoods to a building in an incongruent neighborhood (to most of the congregation), the place of gathered, weekly worship—the building they call “our church.” This is the habitus of Christians within suburban congregations each week. A habit that teaches, forms, and qualifies an understanding of the gospel. The neighborhood is a space we leave for church, more a concept of social structure rather than a concrete place or association; a place where my house is located, but detached from my church experience and faith. This offers a building-centered church experience that more easily relates to the command to love the Lord your God, but has no real, concrete relationship to love your neighbor(s) as yourself. In a real way, a suburban church congregation is without a neighborhood—at least without a specific one. There is no neighborhood for the church to ultimately be identified with, for the members are mostly transported from their actual neighbors and family in real neighborhoods to a one-size-fits-all neighborhood that is stuffed inside a building. Rather than a public faith that engages a neighborhood, practicing the second-which-is-like-unto-the-first-command to love one’s neighbor, more affluent and suburban/exurban congregations form a more privatized, truncated, thin faith (i.e., Christian experience) and, as a result, there is a bent toward more cognitive (knowledge-based) and behavioral outputs (i.e., activities) and outcomes. Thus, the church, the gospel, and discipleship are all aligned with a neighborhood-less social grouping, separated from the day to day realities of life in a neighborhood. Unexpectedly, the early church grew, not because they verbally witnessed, had an outreach program, or held bible studies; but, because they lived their daily lives in contrast to the world around them—their habits were different and their habits were noticed by their neighbors. And, not just in cultured, acceptable behavioral ways, but in concrete, intentional actions. Their discipleship included helping the poor, rescuing exposed (abandoned, thrown away) babies, adopting orphaned children, rescuing prostitutes (temple slavery), and meeting the needs of the widows (who were the most vulnerable and under-resourced population in the empire). This is how the body of Christ, the church, grew. The presence of Jesus was experienced in concrete intentional action through the church—practicing the presence of Christ amid neighbors. Typically for the non-urban churches, evangelism and mission is understood, not by kingdom righteousness, advocacy for injustice, and social action on behalf of a neighborhood, but by numbers of people funneled into a building for a worship service, a bible study, or special fellowship event—a head count of conversions or transfer growth. Church leadership institutes activities and behaviors to draw the unchurched out (and away) from their neighborhood (without actually going into those neighborhoods) and into the building (they call church), which is neighborhood-less (or at least in a neighborhood that is not their own). When the liminality of church life is separated from the daily life of a neighborhood, the gospel and its associated outputs (i.e., activities) and outcomes are disconnected from the life of their neighbors. When one’s own neighborhood consists of those who have had the privilege of flourishing and a church congregation is detached from a neighborhood, the Christian experience affirms a gospel unrelated to the flourishing of a neighborhood. Christian behaviors, then, are limited to relationships and social associations that affirm “traditional” cultural values (within that building) rather than including behaviors that understand the dynamic relationship between structures, systems, and people’s well-being within the context of a neighborhood. The gospel of the suburban church is a limited, one dimensional gospel. A one-dimensional gospel indicates solely a person/God dynamic relationship; whereas a multi-dimensional gospel includes the person/God dynamic and, also, creation/God, person/creation, and person/person. The habits of the suburban and exurban church makes it difficult to see the link between the gospel and the flourishing of a neighborhood.  For a more comprehensive study on the relationship between the gospel and social action, please take the time to read through my Wasted Evangelism, an exegetical commentary on Mark's Gospel. I am also working on another volume on Church Growth from an exegetical study in Ephesians, hopefully titled, Not (just) By the Numbers: Getting Beyond Building-Centered Church Growth in Search of Other Biblical Outcomes—a Thesis on Biblical Temple-Church Growth; see some posts related to these studies (evangelism and Not by the Numbers).  An etymologically based proclamation-centered evangelism is insufficient to reflect the reality of the presence of the kingdom of God, and, as well, disconnects evangelism, not only from the full life of the church, but also from the public and social implications of the kingdom. True, it might be anachronistically incorrect to jump completely from Jesus’ deeds straight to social action, but it is equally wrong to turn Jesus’ parables into mythic stories that affirm “traditional” American values, limited government, and a political and legal agenda that seeks to promote “our way of life” [note A]. Although leaping from the text to “Christian humanitarianism” is an over-simplification, we cannot ignore that Jesus engaged social institutions, nor overlook that Jesus had immense theological conflicts with temple leadership that reached back to Exodus stipulations and their social implications regarding the vulnerable. The kingdom context places evangelism directly in the midst of the public realm where the Christian community is obligated to deal with structural sin and be an advocate for the vulnerable and the poor. Also, to not include social action outcomes in evangelistic activities, limits the possible outcomes where God’s rule and reign can be expressed, realized, and experienced. Such limiting is the result of a privatized and dualistic understanding of the gospel. Rather, a kingdom-centered evangelism allows for the fullness of the gospel to be realized in individuals, groups, structures, systems, and even culture. Evangelistic strategies and actions ought to enact, demonstrate, fulfill, and advocate for outcomes consistent with God’s reign over all the realms of humanity. Evangelistic outcomes ought to include both personal decisions for Christ and actions that promote God’s righteousness and, in particular, social action that engages the needs and welfare of the vulnerable and the poor. Almost four decades ago, David Moberg, in his The Great Reversal: Evangelism and Social Concern, asked how Christians were to deal with the issues of poverty. This continues to be a pertinent question for the Christian community today—let the debate be lively! However, the topic should not be shrunk to public vs. private, government vs. church, or red vs. blue politics. The gospel of the kingdom is “multidimensional and all-encompassing” and is concerned with both the individual and society. Of course, the gospel calls individuals to a right relationship with God, but it goes beyond private piety, calling Christians, especially Christian leadership, to engage, not only with direct action (i.e., social action) on behalf of the economically vulnerable, but also social and institutional structures that work against fulfilling the church’s obligations toward the poor. The Exodus land-laws, operating behind Mark’s programmatic theme, were given to ensure that the vulnerable (i.e., the land-less) were full participants in the benefits of living in the land.[2] Social Action is a means to ensure that the blessings and benefits of living in society reach to the poor. The parable of the Sower who sows encourages the Christian community to waste its seed, sowing it into every realm and every corner of society “in hopes that good soil might somewhere be found,” because it is “our area.” Note A: Actually, it is not altogether inappropriate to make a logical leap from Jesus’ deeds—miracles, exorcisms, healing, over-turning temple-trading tables, cursing a fig-tree, and the ultimate temple-destruction announcement—for it has been noted that some of the miracle stories contain references to actual political referents, and the miracles themselves carry a contrast to a social-political dynamic of crowd control. Note B: For insight on “the land” and the land-less poor, see Walter Brueggemann, Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith (Fortress). *Excerpt from the 2nd chapter of Wasted Evangelism: Social Action and the Church's Task of Evangelism (Resource Publications, an imprint of Wipf & Stock).

Intentional outputs promoting social mapping affirming mutuality and equality among persons10/31/2015 Introduction to the last section: A Temple-Church Architecture Reorienting Trajectory: Personhood OutcomesWith a contextually wider view of the Ephesians Letter, one of the outcomes of God’s cosmic reconciliation through Messiah can be seen in the transformation of the principal Roman social unit into relationships of reciprocity [see Russ Dudrey, “‘Submit Yourself to One Another’," RestQ, v 41/1]. This is even more substantial when we consider that the household code setting is framed within a temple-church venue, God’s new sacred place where believers gathered as the locally enfleshed fullness of Messiah’s body (cf. 1:22-23). Our observations of the code and its literary connection to the Spirit-filled temple-church (see Eph 2:19-22; 5:18) provoke us to reimagine potential relevant outcomes for the significance of how Paul works the household code text (5:22-6:9). The priority of the “lesser” household member (i.e., wives, children, slaves) in each pairing and the leveling of the male head of household through the expected reciprocity to the “lesser” members suggest that personhood (or the recognition of personhood) is an appropriate contextual outcome for the command to be filled in Spirit (5:18c). God’s new humanity (2:15c) is a result (an outcome) of his cosmic reconciliation (his output). Thus, the growing household temple-church in Spirit (2:19-22; 5:18-6:9) is God’s recreated sacred space where (a local) church growth is measured by local “church” habits and intentional outputs that promote a socially constructed reality wherein social mapping affirms mutuality and equality among persons (outcomes). *For those following my thoughts on "Church Growth" here are some concluding thoughts as I prepare for the upcoming November 2015 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta.

Other Not by the Numbers posts >>  R.T. France concludes that the “Mark has declared his hand” in the opening verses of his Gospel [1:1-3], setting the framework in which we are to understand his whole story. We accept that Mark has drawn into his Gospel the motifs of God’s dominion, the Exodus, exile, the Spirit, and idolatry. What is undervalued, overlooked, or even ignored is that the same context that contains these obvious correspondences [from OT contexts in Exodus 23, Malachi 3, and Isaiah 40], likewise, includes direct references regarding socio-economic relationships and community responsibilities toward the poor and vulnerable. [From the chapter on Mark 4, "Wasted Evangelism: Social Action Outcomes and the Church’s Task of Evangelism" in my book, Wasted Evangelism.]  Church leaders should, at least, question who benefits and who does not benefit from current church structures and bureaucracies (i.e., church life and function). The building-centered and business-centric models that most contemporary church-systems emulate can result in duplicitous habits, which can be suggestive of a protective posture for its leaders and for the cultural status quo. Our ways of doing church are not neutral. The temple system into which the gospel is introduced in the New Testament, as well as its leadership, were antithetical to the arrival of the kingdom that had been inaugurated by Jesus’ arrival. Perhaps it is not the construction of temples or the development of religious bureaucracies per se, but the energy and resources used to maintain these systems that promote the status of their own authorities and stakeholders, which can distract (to put it blandly) from a church’s responsibility toward the poor. Rather than laboring to maintain current church systems and structures, contemporary church leaders need to promote the church’s responsibilities to the poor. Otherwise, they may replicate the social and cultural location described throughout the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. The cost of doing church business and maintaining church bureaucracies are not neutral to the church’s role as advocates for the poor. This includes the allocation of human, financial, and social capital available in and through a church or a consortium of churches for use in the public square. Such allocations of financial and human capital could be used for advocating and caring for the economically vulnerable and the poor. The resources and capacity of the local church need to be evaluated, not by our contemporary cultural expressions of church life, but in terms of the kingdom of God, which certainly includes addressing the causes of poverty and advocating for the poor. Andrew Davey, in his book Urban Christianity and Global Order, insists that a church concerned about “its own sustainability must have strategies other than the growth paradigm” (p. 112). Contemporary church growth models are multimillion-dollar business ventures with huge marketing campaigns and an elite celebrity leadership of its own that promote costly expectations for a local church. There should be consideration whether such growth expectations divert resources and human capital away from a church’s responsibilities regarding the poor. While a church’s sustainability should be directed outward and toward the future, it should also have positive, redemptive consequences for the community, with special consideration for its vulnerable populations. Adapted from chapter 1 of Wasted Evangelism, "Widows in Our Courts (Mark 12:38–44): The Public Advocacy Role of Local Congregations as Discipleship."

In the field of social services, of which I have been vocationally related for the last seventeen years, outcomes are an important element in determining what actions are needed. So, likewise with evangelism—if an outcome of evangelism is “personal decisions for Christ,” then activities of soul-winning, witnessing, crusades, and salvation-centered preaching are reasonable; if numerical church-growth is the outcome, then activities that promote such “growth” are acceptable; and, as I posit in Wasted Evangelism, if addressing the issues of poverty and social-righteousness are outcomes, then social action is a valid evangelistic activity. It is not entirely clear that the New Testament presents the concept of evangelism merely from verbal consideration related to the etymology of the word “evangelism.” The early church, especially reflected in the Gospels, seems more interested in creating a narrative understanding of evangelism so future church generations could imagine what it means for the gospel of the kingdom to have been inaugurated. Any attempt to develop a coherent theory of evangelism must begin with the implications of the presence of the kingdom, which is wholly constitutive of the gospel. The parable of the Sower who sows, which fits within this framework, offers a narrative definition of evangelism that includes social action outcomes. *Adapted from the chapter entitled “Wasted Evangelism” on Mark 4’s parable of the Sower who sows in Wasted Evangelism >> |

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed