I don't smoke cigarettes . . . I don't go to the movies or the theater . . . I don't attend secular concerts . . . don't drink coffee . . . go to the beach . . . go dancing . . . fill in the blank. These lines and words are familiar to most evangelical and, especially, conservative Christians. Somehow these lines have been incorporated as a part of our idea of sanctification and how we take a stand against the world–in reality how we define ourselves and the world we oppose. For most of my Christian life I had understood some certain behaviors and places, some types of entertainment, and of course houses of ill repute were sinful, evil, and down-right ungodly–and no Christian should go or participate in such. There is a temptation, however, without some careful thought, biblical understanding, and wisdom, to identify certain activities and venues as evil, ungodly, and "pagan" (unChristian) in and of themselves–almost "just because" (and then attach a Bible verse). There is a tendency among us to simply think the early church condemned certain pagan and civil practices, prostitution, and entertainment because, somehow, such places and behaviors were inherently evil and ungodly. Don't worry, I haven't changed–much–on this thinking, but . . . consider where we might be missing the biblical (i.e., the gospel) point. I won’t dispute the notion entirely, but we need to ask why, what makes them evil and ungodly? In early Christianity, Nero (54–68) had accused Christians of being haters of mankind. Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian (c. 56 – c. 120), reflecting on Nero's post-Rome-burning activities, wrote in his Annals (c. 116):

Nero's indictment of the church caught on. The gathered-church and Christians were accused of being haters of mankind and antisocial (i.e., did not participate in the approved and appropriate Roman social activities). However, it wasn't just because there was something inherently evil, pagan, or sinful in pagan temples (of course idolatry is bad in any form), Roman theaters, religious brothels (there were no other at that time–really), and after-supper symposium entertainment (which included orgies, dancer-strippers, prostitution, and, as well, sexual encounters between adult men and pubescent or adolescent boys). The accusations had more to do with who was welcome at their table (literally), who made up the gathered-church, and how their faith (the gospel and the work of the cross) now defined the concept of being human. These "pagan" practices and venues were antithetical to the nature of the church and who was welcome to participate at the common meal, the Lord's table, and in baptism. The Christian community began to abstain from such activities–and their abstention and their gathering together as church was a challenge and a display of condemnation–because in the gospel and as a result of the cross, the leveling of humanity began to be practiced by the church (i.e., its habitus as a gathered-people). Children (boy and girls), women, slaves, and individuals of differing social, economic, and work classes took on new meaning, new intrinsic value, new dignity to each other "in Christ." Not all human beings were considered equally human or human at all. There was most definitely tiers of human hierarchies that placed a vertical understanding of people, human caste, occupations, age, gender, and ethnicity. When Christians were accused of repudiating and eschewing religious and pleasure practices and institutions of its day—i.e., the theater, temple prostitution, races, gladiator combat, household symposium entertainment—they did so primarily because these venues supported, displayed, and maintained the social and cultural tiers of human hierarchy (now that was and is evil)—not simply because somehow these things were inherently evil. They were venues and practices that supported and maintained social and cultural habits that were inherently racist, misogynistic, de-humanizing, child-abusive, women-abusive, enslavement (i.e., slavery), and thus maintained the evil and ungodly tiers of human hierarchy. All this was challenged by the gospel revealed in the cross and displayed by the gathered-church. This is why the early church was hated. They were accused of hating mankind and of being antisocial because the gathered-church by its very nature and habitus (i.e., how a church practiced being church and how that translated into daily, mundane life and human associations) challenged the status quo of the tiers of human hierarchy. This scared, frighten, and unsettled the gate-keepers, definers, and powers of the social order. I think, today, we're missing this element of a church's presence because of our Christendom-dependent, politically-aligning, homogenous, building-centered church experience doesn't create church in the same way the New Testament and early church was formed and acted. Through who we are as church and how we do church (in much of Christendom today), we have no power to challenge the very places and practices of racism, misogyny, child and women abuse, slavery (of any kind), and any form of de-huminzation of any gender, age, class, or person. Perhaps, it is time and appropriate to reconsider how we do church. For a thread on the nature of the gathered-church as God's platform for addressing and challenging the tiers of human hierarchy >> The Seditious gathered-church.

0 Comments

Walter Brueggemann's "The Liturgy of Abundance, the Myth of Scarcity" seems an appropriate read on this Thanksgiving Day 2017. The link will bring you to an online PDF version of the article. Link to article >>

A Household Gathered-Church: God’s Platform for Challenging Tyranny and Oppression Over two plus millennia, the 4th century Constantinian state-sponsored move away from the household gathered-church created specific social ramifications for the church and for doing church: our building-centered ecclesiastical and liturgical habitus replaced the NT household gathered-church habitus, which has repercussions for social mapping trajectories that have restored tiered human hierarchies and re-segregated church communities into “their-own kind” of social, economic, political, and power assemblies. The household gathered-church has ceased to be God's gospel-centered, cruciform platform for deconstructing systemic tiers of human hierarchy. As a result, this also changed how the church addresses and challenges the current state of injustice, inequality, oppression, and tyranny. There is a tendency to imagine that aligning ourselves, whether as individual Christians or as a building-centered congregation, with power or an influential platform associated with power is the way to bring about systemic change in prevailing tiers of human hierarchy. Tempting as this is, Craig Greenfield reminds the church, it is a trap to think “the solution to injustice is to gain power, hoping that once the roles of power have been reversed,” injustice will cease.[1] History testifies differently—Davids inevitably become Goliaths; the oppressed who seize power become new oppressors. Yet, it was the unassumingly insignificant, powerless, absent any sense of leverage young church that infected every level of society with the gospel and it did so through gathering together—this unique community of the poor and wealthy, property-owners and professionals, business women, slaves, orphans, and abandoned-infants, ex-prostitutes and former temple prostitutes (even some current ones), religious and military leaders, and children, women, and men—at meals in households throughout Caesar’s empire and, eventually, beyond: the gathered-church of strangers and unequals. Through the household gathered-churches invading the very core of the empire, what it was to be human had been “irrevocably altered.”[2] Christianity did not simply offer an alt-system of human relationships and personal morality, but through the very existence of the household gathered-church and its habitus every aspect of the imperial system that created, promoted, and sustained tiers of human hierarchy stood condemned. The way in which the local church gathered and reclined at table was ultimately and completely seditious to the existing system—the system that was foundational to human identity and imperial stability. Celsus, the second century critic of Christianity, described the spread of Christianity as a religion of “slaves, women and little children,” a warning and an argument against the new sect, for it disrupted the status quo ordering of life. David Bentley Hart suggests that it was “unlikely that Celsus would have thought the Christians worth his notice had he not recognized something uniquely dangerous lurking in their gospel . . .”[3] These gathered-churches were made up of unequals and strangers. Their gatherings were traitorous. Their habitus was seditious and dangerous. Their presence, like no other, threatened to destabilize all of society. It is no shock, then, that the church was scorned and persecuted. The gospel shaped gathered-church is not simply one of social integration, but is a scandal to any human institution that systemizes tiers of human hierarchies, be it social, civic, or religious. More than a model or a moment in church history, the household gathered-church, together with its habits, is as much a NT teaching (i.e., instruction to the church) as any other biblical doctrine. More so, everything about the early church challenged the empire, the temple-cults, the religious and political establishment, the business world, and, supremely, all human relationships and associations. Paul and the NT, indeed, did address the issue of slavery, oppression, and human inequality. The question is: does our current form of church? [1] Craig Warren Greenfield, Subversive Jesus: An Adventure in Justice, Mercy, and Faithfulness in a Broken World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016), 95. [2] Hart, Atheist Delusions, 176. [3] Ibid, 115; Celsus reference, On the True Doctrine: A Discourse Against the Christians (trans: R. Joseph Hoffman; New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 38. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Trajectory Application: Two NT Case Studies that Address Tyranny and Oppression (B) The curious case-study of Philemon and Onesimus. The story of Paul, Philemon, and his run-away slave, Onesimus, is as close a NT case study there is regarding how the gospel applies to slavery. The primary objection of some, however, is that Paul wasn’t at all clear nor direct (enough) about it. Our comfort level needs unambiguous NT advocacy against slavery and the freeing of “household” slaves. Yet, this would not have helped slaves in the NT world. Some other social, cultural, and anthropological paradigm shifts needed (and in many ways, still need) to change first—a revolution striking at the heart of tiers of human hierarchy. As was the Greco-Roman world of Paul’s day, advocating for emancipation of slaves can be more about our “enlightenment” than about a slave’s (i.e., a person’s) inherent value, dignity, and equality.[1] Nevertheless, based on the household gathered-church and its habitus outlined thus far, Paul seems to have had something much more ambitious in mind than instructing Philemon to simply free Onesimus. A runaway slave was the most vulnerable of all, a de-housed situation revealing all the aspects of the subhuman caste: any protection in society is absent, confirming Roman citizenship is impossible, all ties to a “household” are lost, and, thus, any rights or security the slave would have had are forfeited. Certainly, a female runaway slave faced certain destitution and probably death. If the runaway slave was a male child of the head of the household (i.e., paterfamalia), he would not have been able to “compete” with legitimate children. A slave was most certainly a filius neminis (a son of no one)[2] and this would have been a perilous state to be on the run. A runaway or even a freed slave would go into permanent social subordination or into exile—not truly free. A slave in the Roman world was denied any legal standing--non habens personam (not having a face) before the law. Onesimus’ options in the real world would not have been at all positive—nor free of the tiered hierarchy of human beings. As Sarah Ruden points out, “This is what makes the debate over the letter to Philemon, concentrating on the question of legal freedom, so silly.” Freeing Onesimus directly into Roman society would have put his life at risk. Had Paul instructed Philemon to free Onesimus apart from the slave’s return to the household gathered-church, it would not have worked out well for Onesimus. Paul desires Onesimus’ return to the safest and most secure place, the one space in the Roman empire where the slave would find equal footing—the household gathered-church. First, Paul’s letter to Philemon aligns well within the venue of the household gathered-church, for it was, after all, addressed as well to the church in Philemon’s house (1:2c). Second, Paul’s appeal to Philemon established them both—Onesimus and Philemon—on the same platform (counter to every cultural thought and social boundary): For I have derived much joy and comfort from your love, Philemon, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you (v. 7); and, Onesimus was to return no longer as a bondservant but . . . as a beloved brother (v. 16). This level position is further established by gospelizing Philemon’s own relationship to Onesimus--but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord (v. 16c)—that he would receive his former slave back as Philemon would receive Paul (v. 17b). Fourth, Paul establishes Onesimus’ status in the community of believers drawing upon his state of “usefulness.” Runaway slaves were nobodies and nothing apart from the “household” because they were useless. The value of a slave was pragmatic, utilitarian, and showed the shame of a tiered human hierarchy. As a runaway, Onesimus was not useful to Philemon, however now he was useful to both Paul and Philemon: Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me (v. 11). The scandal was that Onesimus was “useful” because he was a brother in Christ and was to be received as full member of the household gathered-church in Philemon’s home. Finally, Paul further establishes the relationship status, which reflects the gospel, the nature of the household gathered-church, and the equality of those welcome to recline at table: I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment (v. 10). Heirship—sonship and adoption—was established for Onesimus in terms of the faith. Paul was not merely asking Philemon to forgive his runaway-slave, but to embrace him, now, as a brother in the Lord, a full participant at table: that you might have him back forever . . . as a beloved brother and receive him as you would receive me (vv. 15–16). Paul’s appeal to Philemon is in line with NT teaching regarding the household gathered-church and its habitus. The apostle’s approach, a trajectory application of the gospel, was far more ambitious than making Onesimus legally free—a condition in which Onesimus would have been far more vulnerable—choosing rather to affirm his humanity, that is a full human being within the household gathered-church. Paul’s foresight and application of the gospel in welcoming the former slave into the full ranks of membership in Christ’s church, a “son” equal to his former “master” changed everything—and addresses oppression in the company of unequals. Paul is offering a rather subversive paradigm within the seditious gathered-church that is reflective of the Ephesians household-table. The apostolic and early church, without public protests or any actual campaign against slavery, over time weakened the institution and in some places causing it to disappear. [3] The gathered-church is the space God applies the gospel among unequals that eradicates tiered human hierarchies. Personhood. Although it is somewhat anachronistic to speak of personhood with respect to the Bible, it would not be possible to speak of “persons” today, for our capacity to call someone a person is a “consequence of the revolution in moral sensibility that Christianity brought about.”[4] The concept of person had a far more limited function before the appearance of the gathered-church. The Greek prosōpon (as the Latin persona) was not used to indicate “a person” in a modern sense. The etymological meaning is related to a mask (a false face) worn by actors in a Roman theater. The Roman court system picked up the nuance of persōna, a face recognized before the law. In NT times, it was more accurate to refer to one’s standing before the law than to refer to someone as a person.[5] The “role” an individual played amid social institutions helped prescribe Greco-Roman social mapping as it was diffused through the Roman household. Non habens personam (not having a face) was the lot of most women, almost all children, and, certainly, all slaves. However, the presence of Christianity through household gathered-church habitus penetrated the warp and woof of social mapping. Eventually slaves, children, and women became known as persons. Our ability to acknowledge another as person with intrinsic value and worth originates, not only from the gospel as message, but also from the actual habitus that reformed social mapping. The habitus of the household gathered-church, which met for a meal, a kiss, fellowship, celebration, and apostolic instruction, set in motion the redeeming and, thus, reforming of social mapping, ending tiered hierarchies of humanity. [1] Sarah Ruden, Paul Among the People: The Apostle Paul Reinterpreted and Reimagined in His Own Time (New York: Image Books, 2010), 154. [2] Ruden, Paul Among the People, 165. [3] Ruden, Paul Among the People, 168. [4] Hart, Atheist Delusions, 167. [5] E.g., Jesus did not have “person” before Pilate (Atheist Delusions, 167); e.g., how blacks were not recognized before the law as a person prior to emancipation and the ratification of the 13th Amendment of the US Constitution (December 6, 1865) This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Trajectory Application: Two NT Case Studies that Address Tyranny and Oppression (A) Trajectory application is typically accused of going beyond the text and “modernizing” or “making relevant” the bible’s ancient (and antiquated) sense of things. However, forming outcomes relevant and appropriate to fulfill the meaning of a text should have some biblical foundation to them. In this last section, we will focus two trajectory applications of the household gathered-church found in the New Testament itself: Paul’s Ephesians household-table and his appeal to Philemon concerning the runaway slave, Onesimus. The seditious Ephesian church-household (table). The household was the venue of the NT gathered-church, which is significance, for the Roman household was the foundational institution for the Roman Empire. Aristotle provides the framing of the household we are to imagine in the NT world: “. . . the first and fewest possible parts of a family are master and slave, husband and wife, father and children.”[1] Note the priority of the master-husband-father in his description. Although seemingly inconsequential, recreating the household “in Christ,” changed everything. The belief that a man is “intended by nature to rule as husband, father, and master, and that failure to adhere to this proper hierarchy is detrimental not only to the household but also to the life of the state.”[2] Outside the free male, all others lessened in value and any behavior (i.e., social, civil, or religious) that opposed the centrality of the male head of household was inappropriate, even seditious to the empire. In the Ephesians household-table (Eph 5:21–6:9), Paul tears up the encultured tiered human hierarchy household habitus, and thus, the household-gathered habitus of the worshiping community became the paradigm for believing households. The Ephesians household-table presents three seditious elemental changes to the status quo of the Roman household: 1) the lesser household member (i.e., wives, children, slaves) is addressed first—contrasted with the male head of household who always heads in such tables; 2) a reorientation of the metanarrative for each relationship pair—a contrast to the ordering of life that relies on the centrality of the male in social institutions; and, 3) the reciprocity called upon for each relationship-pair—contrasted with no such male corresponding reciprocity toward the other lesser household members in typical household tables. These three elements are subversive to the culturally embedded view of women, children, slaves, and husbands-fathers-masters. There is a reorientation toward a horizontal rather than a vertical assertion in these relationships.[3] This would have had systemic implications felt in concentric circles out from households to all the nooks and crannies of the social and institutional world. Wives. Statements about women in the first two centuries are difficult for there are nuances of difference among the various social and religious classes and between urban and rural. The value toward the female, however, can be seen in Aristotle’s words: “Again, the male is by nature superior, and the female inferior; and the one rules, and the other is ruled; this principle, of necessity, extends to all mankind.”[4] All evidence in antiquity “unanimously testifies that the supreme purpose of marriage was none other than producing legitimate heirs.”[5] Typically, chastity was a female obligation in marriage contracts, on the one hand, which compelled wives to sexual faithfulness, whereas husbands, on the other, were not bound to such requirements.[6] Although some progress had been made regarding the place of women in the society, the popular association of women imagined at the deipnon/symposium was one of servant, entertainer, or prostitute.[7] Paul reorients the wives-husbands into a relationship built on mutuality, which contrasts with the purpose of a Roman household. This all changed because of the Christian habitus that formed the gathered-church at deipnon and symposium, which then saw women equally at table Children. Modern concern for the welfare of children has no equivalent in the NT world. Affirming the dignity of children was socially counter-cultural, for children were universally “displayed as negative symbols or paradigms” and were “ill-suited portraits for adults.”[8] The preservation of the Roman family estate was the social and civic emphasis, not the protection and prosperity of the child.[9] A child’s life was cheap. Children could face sexual exploitation by adult males, forced into heavy labor, or subject to maltreatment by tutors. The despicable ancient common, practice known as exposure, the abandonment of unwanted infants, is illustrative of the social mapping that declared the centrality of the adult male in the household. Paul’s words on children in the Ephesians household-table would have been striking to all, especially to the male head of household, for whom the compelling cultural and legal focus was his heir.[10] In the NT world, children were “an investment for the future”[11] for the honor of the paterfamilias and for the empire. Household baptism, the kiss, and the table at the gathered-church created a habitus that displayed the intrinsic value of all in the household, including children. Slaves. Informing slaves they are to obey their masters was self-evident in the Roman context. How slaves were viewed, especially as household members, is completely reoriented in the Ephesian household-table. Slaves are told to be obedient to their masters (6:5a), but not out of obligation, but from mutual respect: Slaves, be obedient to those who are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling (6:5). Paul presents the phrase “fear and trembling” differently than we typically hear it. In English “fear and trembling” has a range of connotations: fear of failure, nervous anxiety, cultural respect for someone of higher position. In the NT, however, when fear and trembling are juxtaposed they suggest something positive rather than something negative. Paul joins the two words to indicate the disposition people should have toward each other (1 Cor 2:3; 2 Cor 7:15; Eph 6:5; Phil 2:12).[12] This is reflected in that the master is to show “the same” (ta auta, 6:9a) mutuality to household slaves. Along with being welcomed as equals at table (and in the kiss and as recipients of baptism), this turned the household world of the master upside-down, having rippling effects throughout the empire as the recreated household reflected a seditious reconciliation “in Christ.” [1] Aristotle, Politics (trans. Benjamin Jowett: Kitchener: Batoche Books, 1999); online version, accessed 8/3/2015 < http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/aristotle/Politics.pdf>, Book One, Part III, p. 6. [2] Lincoln, “The Letter to the Colossians,” 653; also A. T. Lincoln, “The Household Code and Wisdom Mode of Colossians,” JSNT 74 (1999): 93–112. [3] Note Spencer, “From Poet to Judge”; also, Lisa Marie Belz, “The Rhetoric of Gender in the Household of God: Ephesians 5:21–33 and Its Place in Pauline Tradition,” <ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/502>, accessed 7/13/15 (Diss: Loyola University Chicago, 2013): 217–18. [4] Aristotle, Politics, Book One, Part V, p. 9. [5] Dudrey, “‘Submit Yourself to One Another.’” [6] Ibid. [7] Kathleen E. Corley, “Were the Women Around Jesus Really Prostitutes? Women in the Context of Greco-Roman Meals,” SBL 1989 Seminar Papers, ed. David J. Lull (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989), 487-521. [8] O. M. Bakke, When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity (trans Brian McNeil: Minneapolis: Fortess, 2005), 21–2. [9] Bakke, When Children Became People, 54–5, quoting Suzanne Dixon, The Roman Family (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 130–31. [10] Dudrey, “‘Submit Yourself to One Another’’’ and see Bakke, When Children Became People, 22–47. [11] Bakke, When Children Became People, 24. [12] Chip M. Anderson, Destroying Our Private Cities, Building Our Spiritual Life (Xulon, 2003), 113. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (C) The Kiss. Whereas Tertullian might have invented the term “kiss of peace” (Or. 18), Paul and Peter indicate that the “kiss” existed among the NT gathered-church (Rom 16:16; 1 Cor 16:20; 2 Cor 13:12; 1 Thess 5:26; 1 Pet 5:14). Here and in early church writings, the abundance of “kiss” references seem to suggest it was not merely symbolism, but an actual, intimate kiss. As one put it, the “kiss” was “a body-centered ritual.”[1] What began as simple greeting became a command to greet each other and, thus, moved to habitus. Although the role of “the kiss” varied within society and at differing geographic locations, the “kiss” was a social-cultural habit in the Greco-Roman world that denoted respect and friendship. There is no surprise, then, that the kiss was an element of the apostolic gathered-church and in the developing early church Eucharistic liturgies. For the most part, the church has institutionalized itself right out of the kissing business. Today, the “kiss” is barely detected at a church gathering save for those that retain the concept as a “pass the peace,” more or less a greeting. However, the Greco-Roman social kiss was a form of respect used to greet another person of equal social status. The kiss was “a symbol of social stratification and status,” a cultural habitus of hierarchy,[2] an “action that joined together two individuals, kissing was a particularly apt symbol for such [cultural and social] border crossings.”[3] The kiss, however, took on a subversive nature within household gathered-churches as it was exchanged among unequals as they assembled at table. All believers—strangers at cross-cultural levels, men, women, children, slaves—at the gathered-church, greeted with a kiss, indicating that such a socially diverse and unequal cohort of people all-together belonged to God in Christ. Since, at the first, their gathered-church suppers were semi-public household events, they risked the slander of on-lookers.[4] People coming together, crossing gender, social status, religious (in as much as new converts and guests had came from diverse religious sects and temples), national, and ethnic divisions—and finding themselves one in Christ. Allen Kreider asks, “Is it possible that Paul and other Christian leaders urged their people to exchange the kiss greeting because it was a practice that could sustain a Christlike habitus across time?”[5] As Eucharistic liturgies developed, “the kiss” prepared the gathered-church for the “table” that followed communal prayers (per Justin and Cyprian). As early as the Didache and Hermas, the “kiss” was understood as reconciliation, a precondition for partaking in the Lords’ Supper (a trajectory application of 1 Cor 11) and, so, “the kiss” preceded the table.[6] That underscored the meaning of the Supper and table, namely their unity (again, the true offense at the table and a fair trajectory application of 1 Corinthians 11). Every act or ordinance created or adapted and used by the apostolic and early church had one thing in common: each accomplished and spoke to unity among earthy unequals. The table, household baptisms, and the kiss embodied a way of defining a new identity and maintaining the bond of a community as a people who didn’t (socially, culturally, legally) belong together.[7] As established habitus of the gathered-church, they were creating a wholly new understanding of humanity-together, a new social reality in Christ.[8] A household gathered-church (multiplied and embedded throughout the empire) was a new living social context of people, a reality of the death of Jesus, creating subversive social mapping that challenged and changed everything concerning the hierarchy of human relationships [1] William Klassen, “The Kiss as Sacred Act in the New Testament: An example of Social Boundary Lines.” New Testament Studies 39 (1993): 122–35; Michael Philip Penn, Kissing Christians: Ritual and Community in the Late Ancient Church (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 123. [2] Ferment, 215. [3] Penn, Kissing Christians, 90. [4] Klassen, “The Kiss as Sacred Act.” [5] Ferment, 215. [6] Ibid., 214. [7] “Radical Intimacy” (Ferment, 216, quoting L. Edwards Phillips, “The Ritual Kiss in Early Christian Worship” [PhD diss, University of Notre Dame, 1992], p. 270). [8] Penn, Kissing Christians, 90, 91-119; note Justin Martyr 1 Apol. 65.2, Chapter 65. Administration of the sacraments: “Having ended the prayers, we salute one another with a kiss. There is then brought to the president of the brethren bread and a cup of wine mixed with water . . .” And “Then the Deacon cries aloud, Receive ye one another; and let us kiss one another. Think not that this kiss is of the same character with those given in public by common friends. It is not such: but this kiss blends souls one with another, and courts entire forgiveness for them. The kiss therefore is the sign that our souls are mingled together, and banish all remembrance of wrongs. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (B) Baptisms. Samaritan “men and women,” an Ethiopian eunuch, the oppressing-Christian-killing Saul, a military Gentile, a Gentile (single?) woman (and “her household”), a Gentile jailor (and “his household”), and an outlier, Corinthian Jew with a Gentile name, Crispus (and “all of his household”) are Luke’s narrative choices of “baptism” stories. Of course, there are multitudes more, but when Luke has a chance to write about baptisms, these are the ones he chose for us to know. In fact, the first time he mentions anyone being baptized after the initial Pentecost events, it is Samaritan “men and women” (8:9; 12).[1] And, the first time Luke tells of an individual that is baptized, it is a foreign eunuch, serving a pagan king (8:36–8). What are Luke’s narrative choices embedded in the “church” story telling us about “church”? The baptism habitus of the gathered-church amid the deipnon (Lord’s Supper) moved people of unequal social status into being “one in Christ” as individuals and as households (which included women, children, and slaves) amid intimacy, reclining among unequals, the risk of being seen as a treasonous gathering (for at a deipnon there were on-lookers), celebrating the death of a traitor acknowledged as Lord and Head of the new social group. Household baptism (along with Luke’s other narrative choices) displayed the counter-cultural and, thus, seditious nature of a gathered-church. This is further seen in NT cross-related texts, that is, trajectory application regarding the unequal “mix” of who made up the gathered-church. Paul links the reconciliation of Jews and Gentiles as a trajectory application of the cross: But now in Christ Jesus you who formerly were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For He Himself is our peace, who made both groups into one and broke down the barrier of the dividing wall, by abolishing in His flesh the enmity, which is the Law of commandments contained in ordinances, so that in Himself He might make the two into one new man, thus establishing peace, and might reconcile them both in one body to God through the cross, by it having put to death the enmity (Eph 2:13–16). This reconciliation, wherein “the both” are created “one new humanity” (v. 15c),[2] is directly related to the nature of the church: “the both” are fellow citizens of God’s household that is growing into a holy temple in the Lord, being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit (vv. 19–22). The unequal-oneness is the trajectory application of the death of Jesus. Later, Paul calls the church to unity through the imagery of its “one baptism” (4:5). Paul associates baptism with Christ’s death: Or do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus have been baptized into His death? (Rom 6:3).[3] This is important, for Paul, then, links baptism to the nature of the gathered-church. The Colossian believers, Paul writes, have been buried with Christ “in baptism” (2:12a) and as a result, they are to set their minds on things above where Christ is seated at the right hand of God (3:1). This is directly related to the Colossian gathered-church’s identity: Do not lie to one another since the old man is laid aside with its practices and the new [man] is put on that is being renewed into the image according to the one who created it, where no Greek and Jew is, that is (kai) [where there is no] circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, freeman, but all things and in all is Messiah [my translation] (3:9-11). The setting is most certainly the deipnon (cf. 3:12–16) and the letter itself most assuredly was read at the after-meal symposium. Furthermore, in other passages Paul links baptism habitus to the associations within the gathered-church: For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:13). The gathered-church exists where unequals are present (and welcome) and there is no ethno-centric center of power. Furthermore, this cross/baptism-nature of church is applied to the gathered-church in Corinth regarding the Lord’s Supper and offers more support for a better reading of the Corinthian “table” issue (1 Cor 11). Paul links their baptism as a sign of their oneness (i.e., one body, 1 Cor 12:13a) and, then made trajectory application of whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (v. 13b) to the issues experienced at the meal/table (i.e., the deipnon). Participation in the Lord’s Supper (the habitus) is itself to be proclamation of Messiah’s death (v. 26, For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until He comes), but was not so in the divisions made at the deipnon food habitus: . . . when gathering together as church, I hear that divisions exist among you . . . Therefore when gathering together, it is not to eat the Lord’s Supper [deipnon] (vv. 18, 20; my translation). [1] My italics to emphasize the inclusion of Samaritan (which is itself impacting) women being baptized. [2] NIV (2011). [3] See Rom 6:4: We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

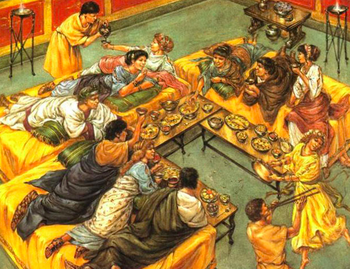

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (A) Doing “church” (and all its accompanying habitus) is a hermeneutic for reading the NT and for making church related application. Herein is our hermeneutical problem: NT documents tend to be read (heard) divorced from the most likely venue wherein they were originally read, heard, and repeated as instruction, that is, at a symposium after a gathered-church had reclined at a household deipnon (supper). NT documents should be read within such an authentic venue-hermeneutic, that is as a gathered-church set at a common meal (this is My body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of Me), the lifting of a cup to celebrate the Lord Jesus (this cup is the new covenant in My blood), and the ensuing symposium where instruction would have occurred. There is significant hermeneutical and interpretive value to the household-venue and, as such, is important for faithful and relevant trajectory application. A Meal and Table of Unequals. As most experience the Lord’s Supper, we find no NT equivalent nor within the first 150 years of church history. Despite the NT calling it a supper, most contemporary forms are foreign to the NT, that is, small crackers and a thimble-sized plastic cup (i.e., tokens of bread and wine), with congregants sitting in theater-like rows (i.e., pews or chairs), and all the action and authority “up-front.” The NT Lord’s Supper habitus centered on who reclined at table; whereas, most modern Lord’s Supper habitus is about the appropriate distribution of the tokens. Something happened at those NT/early church gatherings that was culturally subversive and sociologically seditious. The gathered-church formed its identity within the context of “household” amid habitus that was instructive to them and hermeneutical to us. In the Greco-Roman world, food occasions were a means for creating community and bonding that community together—meals were encoded, social habits were established, and status defined.[1] The habitus of each meal-gathering was a message “about different degrees of hierarchy, inclusion, exclusion, boundaries, and transactions across boundaries.”[2] Men were at the center of such meals and where one reclined at table indicated one’s ranking in society and among his associates. Invitation only. Women and slaves served and did not recline at table. Children were not permitted. However, it was acceptable at these meals for entertainment to include sexual encounters “between adult men and pubescent or adolescent boys.”[3] Depending on social class and wealth, there would have been plentiful entertainment, namely “flute girls, party games, gambling, dramas, mimes, strippers, jesters, moral poems, talks, debate, political, religious, moral, abusive, to erotic discussions”[4] and “sexual liaisons and promiscuities were very common.”[5] Classes did not ordinarily mix. The household banquet-meal was a built-in means for social formation, “a miniature reproduction of Roman society,” serving as a virtual classroom where one’s social status was taught, practiced, and formally enculturated. Social mapping was practiced, a habitus marking identity and social boundaries. The banquet-meal was the imperial instrument for maintaining “social control of the polis”[6] and was utilized “to dominate people and keep them in their place.”[7] This was interrupted by the household gathered-church where women, children, slaves, and men from differing classes and economic status were welcome to recline at table as equals—literally an open table of unequals. The gathered-church adapted, from its NT origin and as the early church took root in the ensuing century, the customary “pattern found throughout their world,”[8] the Greco-Roman household banquet-meal (deipnon) and symposium. Greco-Roman banquet-meal hosts and guests all acknowledged “the gift of food to the gods,” who were understood as the real hosts of the meal.[9] Such meal-gatherings always honored Caesar and some patron deity, which made such meals a blend of social and religious habitus. However, while Romans lifted a cup to Caesar and national deities, local gods, or a household emulate at the bridge between deipnon and symposium, Christians raised “the cup of blessing” in honor of Christ (1 Cor 10:16; cf. 11:23–28). This made each gathered-church at table seditious, for it was not only affirming a traitorous allegiance to another Lord and God, the occasion created a habitus that taught and maintained new identities, removed boundaries, and promoted counter- and cross-cultural relationships. However, the nature of the gospel and trajectory application of the cross brought about a challenging social-mapping: an ecclesial-demographical mapping of unequal people outside the banquet hall, yet who reclined as equals at table. Adapting the Greco-Roman evening deipnon/symposium set a household gathered-church on the eve (i.e., Saturday evening) of the Lord’s Day (i.e., Sunday), which accommodated the poor and slaves and working children that could not have attended an early morning “service,” for history had yet not giving us a 6-day work week with Sunday off.[10] The wealthy and upper-class church attenders had more power to adjust their daily schedule; the poor and destitute could not. Furthermore, this history and a household-venue hermeneutic allows a fair reading of the deipnon-table and Lord’s Supper issue in 1 Corinthians 10-11 to be about “haves” that were separating (or distinguishing) themselves through food habitus from the “have nots” at the Lord’s table. In this way, the gathered-church-temple (1 Cor 3:16–17; cf. Eph 2:18-22) was being destroyed (1 Cor 11:18–22). These meal-occasions failed, literally at table, to display love toward one another (the reason for chapter 13), thus they had ceased to eat the “Lord’s’ Supper,” abandoning the gospel-ecclesial social-mapping and habitus purpose of the meal.[11] [1] Lanuwabang Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement in Fellowship Meals: The Socio-historical Background of 1 Corinthians 11:17–34 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2016), 3; quoting Robertson Smith from his Religion of the Semites (page 217); —eating was understood as a sacred, mystical act when done together [2] Mary Douglas, “Deciphering a Meal,” in Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology (London: Routledge, 1975), 249–75, 249. [3] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 17; less so among Jewish households, but still drinking and other forms of merriment were very central to the latter, symposia, part of the banquet. [4] Ibid, 16. [5] Ibid, 17. [6] Street, Subversive Meals, 9. Italics original. [7] Ibid, 15. [8] Street, Subversive Meals, 11. [9] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 15. [10] Ferment, 191; note: Justin, 1 Apol. 67.3; Origen, Hom. Luc. 38.6 [11] Street, Subversive Meals, 37; a similar venue-hermeneutic reading can be made of the James 2 “church” text. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Believing households and baptisms. The how seems irrelevant to Luke’s accounting, but the fact that believing households and baptisms are embedded into the story of the gospel spreading geo-demographically into the Gentile world should carry some hermeneutical and interpretive impact on our understanding of “church.” In Acts 2:41, Luke tells us that those who had received Peter’s explanation were baptized, indicating that “3,000 souls” were “added.” Most translations attempt a specific period of time.[1] However, the en (in) might very well lend the phrase (lit., in the day that) a figure of speech rather than a duration of time (i.e., 24 hours). Plus, “3,000” might be a cryptic reference to God’s judgment under Moses when 3,000 Israelites were struck down for their calf-idolatry (Exod 32:28). Three thousand would have been a “riot,” an unlawful assembly; and, all “3,000” hearing Peter, literally on one day (“on that day”) would have been near impossible. Luke is most likely summarizing and compacting the time and numbers. It would not, however, be a stretch to recognize Luke’s “added souls” (i.e., converts) and the reference to “baptism” over time (i.e., at the time of the Pentecost feast) rather than all at once (i.e., in that very day following Peter’s Pentecost sermon). It is not unreasonable to assume multiple baptisms, then, took place within the household-venues of those “added,”[2] for Luke’s narrative summarily and specifically put “conversions” and “baptism” in household venues (house to house, et al.). The “households” we are to imagine are not the modern, nuclear definition of family—a couple and dependent children within a home. Households of NT times were composed of far more than a simple, nuclear family. The household of the NT world we are to imagine was composed of a head of household male, his wife, grand-parents, children and later their spouses, children of household’s children (i.e., grand-children), other close relatives, slaves (indentured, bound, and free), as well as the wives[3] and children of the slaves. So, the narrative imagery of a household believing and/or baptism had a far reaching, cultural impact, and thus, for our understanding of “church.” Conversion stories abound in Acts, interestingly, most chosen by Luke are of societal outliers, those on the margins, foreigners, those deemed less than human (i.e., less than a male Roman citizen), Gentile military, or among the Jewish diaspora. Luke’s narrative choices are instructive and suggest an appropriate trajectory application of Acts 2. His choice for the first individual to believe is an Ethiopian Eunuch (8:26–39), a foreigner and unclean outsider. The first European convert is a lady, Lydia, where Luke indicates that she and her household had been baptized (16:15a); next a Roman jailer who was baptized, he and all his household (16:33; cf. 16:31)[4]; and, then as the gospel penetrated beyond Athens and into Corinth, we find Crispus, the leader of a diaspora synagogue that believed in the Lord with all his household[5] (18:8). Finally, Paul references his missionary/church-planting activities from house to house (20:20). Luke’s narrative choices and continual references to household “believing” and “baptisms” are a remarkable story-line that informs and forms how the gospel was “applied” as it spread into the Gentile world—and how we are to read “church.” It was primarily through households, of which some became the gathered-church venue for fellowship (the deipnon), worship, and instruction (the symposium), which very early on, as will be discussed below, was composed of believing households and baptisms that included women, children (both male and female), slaves, and, of course, men—of all ages and social status. The gathered-church in these households would have hosted the deipnon (i.e., common meal and Lord’s Supper) and the symposium that followed and, thus, contrary to the nature of Greco-Roman banquet-meal, unequals in society and culture would have been welcome, reclining, and cared for participants. This formed the nature of the gathered-church and its habitus. [1] E.g., that day, NASB, RSV; that same day, KJV; et al. [2] Though Luke certainly means “added to the number of believers,” what the “added” were added to is left unstated. We’d expect “added to the church” (and we tend to take it that way). However, the ambiguity is worth noting in that the concept of “church universal” has yet to develop and is actually absent in Luke’s accounting; what is present is church “in” a place with the emphasis on “house” as where believers met and instruction to place. This, then, would lend for the imagination to see the "added" being baptized within the “house to house” of gathered-believers. [3] Slaves had no legal means for marriage, so “wives” were female slaves attached or pledged to a male slave. [4] The Greek in v. 33 is simply “he and all his,” household being implied by Luke based on 16:31. [5] Baptism is assumed; cf. 18:8c This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

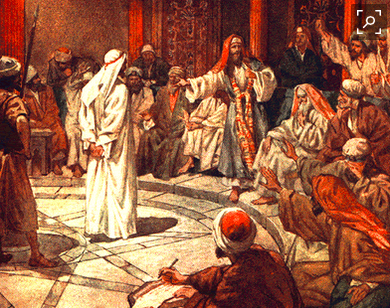

A Household Table-Waiter Preaches. Luke’s story of Stephen’s sermon before Jewish leaders (Acts 6:1–7:60) is framed by the gathered-church household-venue (5:42; 8:3; cf. 2:46). At some point the widows of Hellenist converts were being overlooked in the daily serving of food (Acts 6:1c) at the deipnon (i.e., supper) component of the gathered-church. The Acts 6 setting assumes a house-venue (from house to house, Acts 5:42) where the Greek-speaking widows were to have found a place at table (certainly a trajectory application of the distributed Spirit upon aged women!) As a response, the twelve (apostles) determined their role was prayer and the ministry of the word (Acts 6:2) and that reputable, Spirit-filled men were to be selected to serve (diakoneō) tables at the deipnon and care for the widows. Men! Not slaves. Not women. This was an astonishing trajectory application of the gospel and the inaugural distribution of the Spirit. Men did not do this in a Greco-Roman household. Furthermore, when Luke choose his very first scene afterward for the “ministry of the word,” he does not pick one that included an apostle; it was a table-waiting lay-person from among the household gathered-church, Stephen. Furthermore, we should not treat lightly the “house” theme in table-waiter Stephen’s defense before temple-leadership, for he draws upon a text that deconstructs temple-imagery and his trajectory application constructs God’s new dwelling of “house.” Stephen quotes Isaiah’s words to Jewish exiles to stress that the Most High does not dwell in anything made by human hands (cheiropoiētois): ‘Heaven is My throne, Given Luke’s “house” theme elsewhere,[1] it is not a stretch to answer the Isianic question--What kind of house will you build for Me?—by pointing to the newly distributed Spirit among the household gathered-churches. And, after Stephen is stoned (Acts 7:54–60), Luke’s narrative pans straightaway back to the house church venue as Saul makes his arrests from house to house (8:3). The first narrative contrast to the temple is the new resting place of God among believers, that is “house to house.” [1] Note the 14 house-banquets in the Gospel of Luke and the numerous occasions in Acts. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed