First a sermon illustration to start us off: There is an old illustration of Hell that still speaks and I think it sets up my point from Luke 6:37-49: Hell is like a long banquet table with all sorts of food and delights, but everyone at that table is getting thiner, more gaunt, more haggard from hunger. They are starving with all that food before them. You see, the utensils they were given and had to use were six foot long chopsticks. If they’d only thought unselfishly and fed each other, no one would be starving and all would be enjoying the great banquet. Thus, the Adamic nature of the human-being and why the existence of Hell. Now, the point of the illustration, here, is the audience of Luke’s Gospel, the listeners/readers before the text, that is, those house-churches (associated with Theophilus) with believers sitting around those tables enjoying a meal (aka breaking bread) and lifting that fourth cup of wine at the end of the supper, celebrating together and acknowledging that Jesus is Savior and King. And us, now . . . Still, for now, imagine those tables with former enemies and individuals of clashing social status all confessing Jesus is Lord, a new fellowship of unequals and strangers. Love your enemies and stop judging makes applicable, narrative sense (Luke 6:27, 37). It makes church sense. So, let’s take a look at the text and context, beginning with Luke 6:37-38a: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive, and you will be forgiven; give, and it will be given to you” What do we have here? There is an obvious structure that helps us read it properly:

This whole pericope (i.e., set of commands) should be taken as one thing. Yet, still there are questions begged to be asked . . . ➤ Stop judging what? And, what will we be not judged of? ➤ Stop condemning what? And, what will we be not condemned of? ➤ Forgive [others] of what? And, what will we be forgiven of? These are all left open-ended, unanswered by the command and promise. Most supply don’t judge sin in others and sin will not be judged of you . . . forgive others of sin and sin will be forgiven you. We might infer this, but the sentences do not demand or necessarily imply this reading. Now, the last command . . . ➤ But . . . the “give” is already in the context and, thus, can be applied to the whole: “Give to everyone who begs [“borrows” is a far better reading] from you, and from one who takes away your goods do not demand them back” (Luke 6:30); “And if you lend to those from whom you expect to receive, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, to get back the same amount. But love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return . . .” (vv. 34-35). So, how does this help us with reading and applying this element of the Sermon on the Plain? Pretty much most see the judging and condemning related, as I mentioned, to sin--you know, don’t judge the sins in others (i.e., the specs) before you deal with the sins in you (i.e., the logs/beams). Nothing in the text nor the context warrants this reading. However, something else is within range. Let me suggest: there is a social and cultural association/relationship implied that I believe we can reasonably and appropriately infer. We have the “poor” and the “rich” already referenced in the Beatitudes (vv. 20-26) and there are the references to “enemies” (v. 27b), “those who hate you” (v. 27c), “those who curse you” (v. 28b), “those who abuse you” (v. 28b), “the one who strikes you on the cheek” (v. 29a) and “the one who takes away your cloak” (v. 29b), including “the one who begs from you” (v. 30a) and the “one who takes away from you” (v. 30b), and, especially, there is the patronage giving-lending-for-return (vv. 32-35)–all pointing to social and cultural castes of relationships (very much the poor/rich referents mentioned in the Beatitudes). . . this “giving” et al. idea is drawn into this set of instructions (as already pointed out above), which, based on how the instructions is structured, infers to the whole (all of the commands). Simply: stop judging-stop-condemning-start forgiving-start giving is an extension of “love your enemies . . . do good to those who hate you, which leads to the give/lend expecting nothing in return.” Seriously, this reading actually solves the “poor” and the “rich” referents . . . and supplies how it is the “poor” and the “rich” are now breaking bread together as members of the family of God (around those tables). There is a social and cultural shift amid the new community of God in Christ Jesus around those tables—something both attitudinally (i.e., renewed in mind) and concretely (i.e., a behavior, a lifestyle that is) different, wholly distinctive about this community of Jesus followers. There is something missionally different (and imperative) and something intrinsically different (relationally), even something ontologically unalike the social and cultural milieu (the social location, what makes the empire adhere and maintain, the tiers of human hierarchy) that surrounds the church–these congregations, these tables, these local, neighborhood house-churches are a new creation, unlike anything else now or before. Missionally important because this redemption in Christ is for all people—using Paul’s language in Romans 1, for the elite-Greek, barbarian, Jew, educated and uneducated; using Luke’s (i.e., Jesus’) the poor and the rich, the beggar/borrower and the lender. The message itself (i.e., the gospel), those to whom the message was to be shared (missional importance), and the new relationships at those tables need to match, align. Thus, enemies are also to be loved—out-there among those to whom this gospel would offend and threaten, these cultural enemies. First, all made visible at those tables of gathered Jesus followers (i.e., disciples). And, made outwardly relevant by doing the same among neighbors and in the community. Can’t reach and minister to those whom you are judging and condemning—and I take this to mean socially and culturally judging and condemning (given the narrative context) . . . and as such among the socially and culturally unacceptable* (read both ways—poor to rich, rich to poor) that we are to love, do good, forgive, lend, give) . . . and this gospel is made visible and real around those tables throughout the local house-churches. It seems, given the diversity at those tables and the new rules (if you will) of who can and should be at the table, there would indeed be a need to stop judging/condemning and a whole lot of forgiveness to go around and new patterns of giving to be had. There is no privilege (or patronage) at that table. There is no cursed at that table. Only new relationships in Christ. Given that the Sermon on the Plain ends with the house parable, which speaks to the actual house-church-settings (Paul uses the same in Ephesians 2) and is about discipleship, specially listening to (meaning, obeying) Jesus’ words—those who hear and does them—what I have proposed here seems a good, reasonable (exegetically, narratively, and contextually) faithful reading of the Luke text regarding “judging” et al. And, thus easily and significantly applied to our own church fellowships and witness (mission). *socially and culturally unacceptable are those in castes that are despised, shunned, hated, outside blood-lines, social groups, vocationally loathed, economically reviled, and religiously held in contempt (of which the Christians because of whom they follow and because of this new socially destructive teaching would also find themselves)--this can, nonetheless, be applied (i.e., done) reciprocally from one group/caste to the other and visa versa. Other Sermon on the Plain Wasted Blog thoughts

2 Comments

Recently during a Sunday sermon on Matthew 11, I asked: “How do you think the young church, with nothing much to offer, no social or political power, possessing little resources—and life didn’t really get easier and better for early believers. They risked everything, and for most, life got harder. How do you think, in the first 150 years after Pentecost, Christianity became the largest religious sect in and around the Empire? How? “They changed their households . . . street by street, village by village, at the table [I pointed to our table where we would shortly celebrate the Lord’s Supper together]. It all changed right here where gathered-churches lived out ‘Come all who labor and are heavy laden.’ “The body of Christ, the local church, with Jesus our Head, ruling and reigning at the Father’s right hand, is His presence in its community. We show them Jesus by who we are and what we do so that all who struggle and toil and are carrying burdens no one should carry alone hear (because they see) the invitation to Come to Jesus and take on His yoke and find rest. We are to embody the invitation to Come.” ¿Como piensas que la iglesia naciente sin nada que ofrecer, sin poder, careciendo de recursos? - y la situación no se puso ni mas fácil ni mejor para estos primeros creyentes que se arriesgaron todo, sino la vida mayormente se les hizo aún más difícil - ¿Como piensas que dentro de 150 años el cristianismo llegó a ser la religión más prominente en y alrededor del imperio Romano?

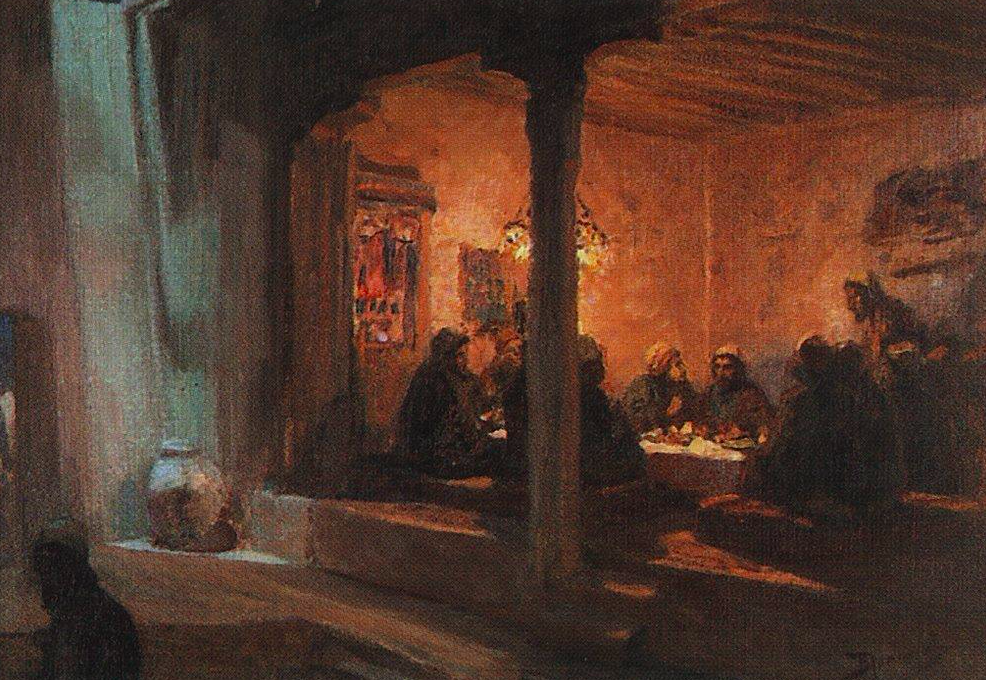

¿Cómo? Ellos hicieron cambiar sus hogares ... calle por calle, aldea por aldea, en la mesa. Todo se cambió allí mero, donde las iglesia reunida practicaba el "Venid a mí, todos los que estáis cansados y cargados." El cuerpo de Cristo es la iglesia local, con Jesús como nuestra cabeza regiendo y reinando a la diestra del Padre, su presencia en esa comunidad. Les demostramos a Jesús por quienes somos y por lo que hacemos para que todo aquel que lucha y labora y que lleva carga pesada no lo haga a solas porque oye y ve la invitación de venir a Jesús y tomar su yugo y hallar descanso. Debemos encarnar la invitación a venir.  There are so many grand and wonderful paintings of early church times of table fellowship. And some I really, truly like. Yet, there is a male-centerness to them that would not have reflected the actual tables of Christian fellowship of the early church that these scenes are to depict. I do not see women and wives and slaves and children; typically just men, and when women are depicted, they are serving food. Most of these grand paintings were created and come at the time after Constantine, the Roman Empire Caesar (272 AD - 337 AD), herded the churches away from the homes of Christians and into buildings sanctioned by the State, along with laws to build up and protect an appointed church authority and priesthood consisting solely of men. Church began to reflect the culture of the empire more so than the one painted by the Apostolic church and the early church through 300 AD. This move recreated church away from the Table fellowship of strangers and unequals that had increased and spread since the days after the Pentecost of Acts 2. Most of these wonderful paintings, as far as I can tell, come from the post-constantine Christian era, reading their “church experience” back into the apostolic and early church (form and experience). We do that, too, now. We start with how we do church now and read it back into the New Testament accounts and teaching--this anachronistic. Our vision of the church not only reflects the flaws and the unredeemed aspects of our social and cultural times (and trends), but we read this experience of church back into the life of the early church and, worse, back into the vision of the church depicted by our New Testament writers. We need to do better.

The goal of redemptive history is the cosmic restoration of creation. This is the story of the Bible. This is the church’s story. This should be your church's story. God has determined to use a redeemed people to herald this message. The ekklesia of Jesus, the gathered-church, composed of redeemed and restored people, living out the gospel, illustrating this cosmic restoration through its treasonous worship of the risen Jesus, the Lord over all other claims to the throne, its missional behavior to its neighbors, and , particularly, through the fellowship of restored human relationships among strangers and unequals. The gathered-church of the Lamb of God is unlike any and all other rebellions and resistance movements: church is not (ever) aligned with a government or party or state or king in order to violently overthrow or by means of State-authority and any form of violence to maintain; church is never (ever) aligned with the spilling of blood through strength or cunning to change or maintain the status quo of an unredeemed social structure or cultural state of affairs; and, where privileged to participate, church does not count on the ballot-box to overthrow power or maintain a particular person or party in power. The church uses a table of fellowship over food, broken bread, and a raised cup of allegiance to the risen King of kings and Lord of lords, now seated at the right hand of God in the heavenly places. This has been and is God’s way of, not saving the State or some preferred demographic or cultural value, but demonstrating that all of history is moving toward His ultimate conclusion of a restored creation. How does God reveal and accomplish this purpose of history? Little and grand tables, scattered throughout time and place, some well noticed and many hidden in the back alleys and among the margins–this has been where God does his rewriting of corrupted history and the deconstructing of the powers of humankind. This is church-story. Not just the best story. But the true story of history. This is the story you and I are invited into; and, the gathered-church is the place God restores all things. Not the battlefield. Not the ballot box. But at tables of strangers and unequals.

Power does not naturally distribute power equitably. This is why, first and foremost, calling upon the powers to distribute power more fairly (whether government, industrial complexes, religious institutions, or business corporations) will not address the problem of power being more equitably distributed. When politicians and civic leaders get elected or into positions because they promise more equitable distribution of power, once in power, they have an idolatrous temptation to remain in power over the very people they claim to advocate for—so, they, too, will not naturally be given to share that power more equitably. As was once said, power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely. The only place power is distributed equitably is at that Table in the (better, yet, a) gathered-church. And, this is exactly what happened in the Book of Acts. This is the background of New Testament Letters like Romans, Galatians, and James; and, for the early church (for the first 150 years or so) . . . and, which, now, should be happening at every gathered-church of strangers and unequals in every locale, on every street, in every neighborhood, and within every community. This is at least one reason why the church, a the local gathered-church, is so, so important. Where this isn’t happening in a local church (i.e., a gathering of strangers and unequals at worship and at Table), there needs to be lament and repentance and correction in righteousness. Our problem is that much of the church (local and institutional) has so aligned with Christendom (that is, a culture that steals from Christianity just enough to control the industrial-church-complex and its own citizenry, but is formed by power-idolatries, such as ours here in the West) that, we, too, have become a power (or powers) that do not naturally distribute power equitably. But this isn’t the gospel, nor is it the body of Christ prescribed in the New Testament. But we didn't learn Christ this way (Ephesians 4:20; cf. 4:17–32). Yet, this is the place (the gathered-church) where power is defeated (Ephesians 6:10-12; Colossians 2:15) and the place where the only power known is the crucified power of the cross of Christ (Gal 2:20). This is the place where “there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female” (Gal 3:28); for this is the place all, by one Spirit, have been “baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit” (1 Corinthians 12:13); a space “where no Greek and Jew is, that is (kai) [where there is no] circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, freeman, but all things and in all is Messiah” (Colossians 3:11, my translation). Given that we are subject and, too often, align ourselves to the powers (at least the side of power we like or identify with or the side that seems to give us power, which is an illusion, of course). It is too natural to believe our only recourse for justice is to call upon those in power (i.e., the State or the industrial-complex) to give up power and more equitably redistribute power. But they will not, no matter how much they promise. However, the harder work—which is God’s way in this world now that Christ Jesus has died, been raised, and ascended to the right hand of the Father, and the church, the local gathered-church is His body, His presence in a community—the harder work is ecclesiastical, not simply protest, advocacy, and, certainly not, voting correctly. Our contemporary church-power and the way we tend to advocate in the public square mimics the current systems of power, so it is natural to have “Christian leaders” gain power, who develop followings as a demonstration of their power, to call upon the powers of government and systems of power to do justly. And to punish those who do not. So, what we have—what we end up with--is only “power” vs. “power.” But what God wants is crucified with Christ-power among the church, that is, our local churches (rural, suburban, exurban, and urban), and in church planting (especially in the harder places, the hinterland places, the geographically “unlivable” (and unlikeable) places, the marginal places, the border-places, the places where there is the lack of power).

There is no doubt in my mind. There is no way around it. The issue and problems of justice are a Table issue where the gathered-church exists. We are called to the harder task, church, where justice, that is, the place where the more equitable distribution of power can be experienced, demonstrated, and displayed.

I am developing a paper (and chapter in a forthcoming book), "The Seditious Household: How Holy Kisses, Tables, and Other New Testament Practices Confronted Tyranny and Oppression." The paper will deal with how the early church--literally and more accurately, how early household-churches--leveraged their only power, namely their open (everyone welcome) house-church gatherings, against the powers of oppression and slavery. We, today, need to rethink our strategy or all we do is trade powers (theirs) for another power (ours), exchange one oppressor (them) for another (us). The big question for Jesus followers is how did he conquer and change what the powers had control over: through a Holy Kiss, a Table, Baptism(s), and Households. We need to return to that Holy Kiss, that Table, Baptism(s), and Households. ReRead the Acts and you'll get a hint. Jesus, the NT Jesus anyway, isn't simply a spiritual adviser; he is a king and a priest and a prophet, making him aversive--an political opponent to the powers in place in his day (which did not have any wall, fence, or divide between "church" (i.e., religion) and state. His life, the cross, and the resurrection confronted, disarmed, and overturned all the powers contrary to God's rule and reign. Recent research has acknowledged the “mission” and “witnessing” were not actually sited as the purpose or compulsion for the early church. Combine this with the clear fact that we have in Acts of the Apostles only the leadership—and actually only a few here and there—publically proclaiming the gospel. Inspired narrative doesn’t give us a picture of early church Christians “gossiping” the gospel, or offering a “Four Spiritual Laws” or even an Evangelism Explosion “If you were to die . . . what reason would you give for God to allow you into his heaven?” approach. What we do find is the gathering of unlikely participants—slaves, children, woman, along with the men, and the increasing of differing ethnic backgrounds—gathering on equal ground around a meal in a household, multiplying throughout the Roman Empire. Regarding slavery, my thinking was affirmed by a book review I read: despite our wish that Jesus and Paul had simply announced the evil of slavery (which they did not, at least in a clear way we’d appreciate and proof-text), we need to understand that they were after something higher, something more significant. (More important than ending slavery, condemning slavery! you might be tempted to judge too quickly.) Jesus and Paul upped the ante to a much more noble idea, the dignify of being a human being. Paul and Jesus (and Luke in Acts for that matter) had something much more ambitious (as the book being reviewed had stated) than advocating for slaves to be legally free (which would have been good for our comfort levels and political agendas, but actually not so much at that time for slaves). First and foremost, Paul and Jesus wanted the church to see slaves as human beings. They wanted to make them into human beings. This—slaves along with making children and women—into human beings (which they had always been, but you know what I mean)—is what changed everything, unhinged an empire, and its shadow (this approach and paradigm modeled by Jesus and the NT writers) has caste itself as the gospel moved demographically and geographically. This should be what the church is about: making others, especially the marginal, the oppressed, and disenfranchised into human beings. Albeit, the first mentioned of those being baptized in Acts is after the Spirit fell in chapter 2, but Luke’s narrative choices about baptisms is quite informative: Samaritans (“men and women”), an Ethiopian eunuch, the oppressor, Christian killer Saul, a military Gentile, a Gentile woman (and “her household”), a Gentile Jailor (and “his household”), and a outlier, Corinthian Jew with a Gentile name, Crispus (and “all of his household”) are the list Luke gives of those who were baptized. I didn’t include Simon, the magician, for his baptism was a fake, not real, and was used for his gain, not for entrance into the faith. Of course there are multitudes more, but when Luke has a chance to display and write about baptisms of believers in Messiah Jesus, these are the one’s he tells us about. The first time he mentions a believer being baptized after Pentecost it is Samaritan men and women; and the first time Luke tells us about an individual who believes and is baptized it is an foreign-gentile, eunuch, serving a pagan king. Not stop and think—what is the story, Luke’s narrative decisions, telling us about baptism and the spread of Christianity? "Though the Spirit continues to move, the assembly that is described in the New Testament with all the believers in the one fellowship of Jesus Christ and meeting in homes, house by house, is almost completely neglected. The true assembly has no hierarchy, nor man’s organization. Hierarchy is defined as levels of authorities to direct and control believers. All the various ministries should be for the building up of the assembly, but instead the opposite occurs. Whole churches are formed around various ministries. Not only are major denominational churches formed around powerful ministers such as Luther, Calvin and Wesley but also every church today is centered on the ministry of a particular teacher or preacher." - Henry Hon

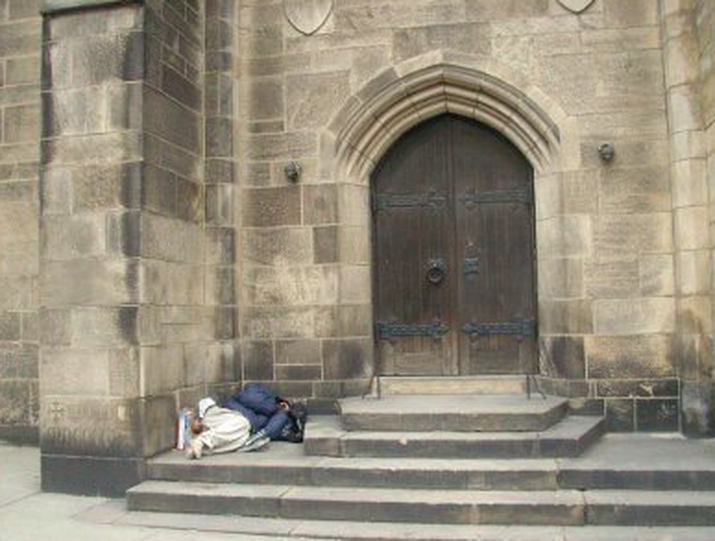

The small, powerless, nothing for leverage young church grew; they believed they were actually citizens of the kingdom that Jesus preached and now they, too, were to announce it too . . . and it seems that they did so through gathering together--this unique community of poor, landowners, business women, slaves, children, ex-prostitutes, former cult and current military leaders, and women--gathered meals in households through Caesar's empire and, eventually, beyond. The gathered church that met “house to house,” in a family’s meal room was the platform for both proclamation of the gospel (in instruction and in reenacting the Lord’s Supper as part of a communal meal) and, as well, a seditious act against Caesar, the god’s of the empire, and the tyranny of oppressive forms of de-humanization. For the Cup was raised for a dead (but now alive) insurrectionist rather than for Caesar, the gods of Rome, or local family deities. The Broken and shared Bread was a declaration, not of Caesar’s provision or pf the gods, but of the dead (but now alive) insurrectionist’s provision for the forgiveness of sins—for all people. For, the leverage of the gospel proclaimed and enacted in the household-church gathering (the church’s only leverage) was who reclined (yes, actually reclined) at table for fellowship and eating and drinking. Breaking every known cultural and social etiquette and acceptability of the day, of the empire. The church’s only leverage for its seditious church gathering around the meal and the Cup and the Broken Bread was a gathering of a community of poor, landowners, business women, slaves, children, ex-prostitutes, former cult and current military leaders, and women. The form of the household church gathered (literally reclining) around a table and eating and drinking was a true and faithful representation (literally an outcome) of the gospel of Jesus, the Messiah. Moving the gathered believers away from homes and into addressed, concrete buildings and removing the meal-feast-banquet from the center of the gathered who came for worship, fellowship, and instruction were the first moves for the church away from caring for the poor upfront and personal; and, the first step in refusing to believe Jesus' words, "the poor, you will always have among you."

Been dwelling some in Luke’s parable of the Father, stay at home son, and the prodigal son. First, the trio-parable set in Luke 15 is not about our individual salvation nor a focus on simply the Father’s love for me--it is incredibly more and speaks loudly to the habits and the forming of church. We need to hear how, in fact, Luke starts chapter 15: “Now the tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribes grumbled, saying, ‘This man receives sinners and eats with them’ (vv. 1-2). So, the issue is pretty clear: The temple-leadership had a problem with Jesus’ welcoming of the unclean, marginal, socially unacceptable and despised to the table of fellowship. What is often overlooked in the wider context is that Luke’s chapter 15 set of parables is surrounded (preceded and followed) by “feasting” and “eating” lessons. (We’ll get to this in a moment.) Additionally, Luke’s three-parable set is also about “feasting” and “eating.” For in both the first two Luke 15 parables, after what was lost is found, there is a gathering of friends and neighbors for rejoicing: “And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost’” (v. 6). Likewise when the prodigal son returns, he is welcomed into a feast as the honored guest (vv. 24-27).

The wider narrative in Luke suggests that it is whom we invite to these “feasts” and times of “eating” that is at issue. For Luke 15 is bracketed by chapters/stories of "feasting" (i.e., "eating"). First, there is the parable about proper kingdom table etiquette (the inviting of the marginal and socially unacceptable) vs. the acceptable social norms (chapter 14) and, then in the preceding chapter, the story of a rich man, who “feasted sumptuously” and poor Lazarus, “who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man's table” (16:20-21). The lost-dead-prodigal-son isn’t just a picture of the wayward sinner, the lost law-breaker, but is a figure representing--to keep with Luke's theme--the socially unacceptable that are now welcome, equally, without hesitation or qualification (save faith) to God’s kingdom table. These parables, including Luke 15's parable of the prodigal son, are forming for church and missional church-life. Luke 15 is one of the parables that scream out: “Go do likewise!” Who are you eating with? Who are you intentionally inviting and compelling to come be a part of your local church? Maybe even more so, who are you making second class citizens of the kingdom by how we do church? |

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed