Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (B) Baptisms. Samaritan “men and women,” an Ethiopian eunuch, the oppressing-Christian-killing Saul, a military Gentile, a Gentile (single?) woman (and “her household”), a Gentile jailor (and “his household”), and an outlier, Corinthian Jew with a Gentile name, Crispus (and “all of his household”) are Luke’s narrative choices of “baptism” stories. Of course, there are multitudes more, but when Luke has a chance to write about baptisms, these are the ones he chose for us to know. In fact, the first time he mentions anyone being baptized after the initial Pentecost events, it is Samaritan “men and women” (8:9; 12).[1] And, the first time Luke tells of an individual that is baptized, it is a foreign eunuch, serving a pagan king (8:36–8). What are Luke’s narrative choices embedded in the “church” story telling us about “church”? The baptism habitus of the gathered-church amid the deipnon (Lord’s Supper) moved people of unequal social status into being “one in Christ” as individuals and as households (which included women, children, and slaves) amid intimacy, reclining among unequals, the risk of being seen as a treasonous gathering (for at a deipnon there were on-lookers), celebrating the death of a traitor acknowledged as Lord and Head of the new social group. Household baptism (along with Luke’s other narrative choices) displayed the counter-cultural and, thus, seditious nature of a gathered-church. This is further seen in NT cross-related texts, that is, trajectory application regarding the unequal “mix” of who made up the gathered-church. Paul links the reconciliation of Jews and Gentiles as a trajectory application of the cross: But now in Christ Jesus you who formerly were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For He Himself is our peace, who made both groups into one and broke down the barrier of the dividing wall, by abolishing in His flesh the enmity, which is the Law of commandments contained in ordinances, so that in Himself He might make the two into one new man, thus establishing peace, and might reconcile them both in one body to God through the cross, by it having put to death the enmity (Eph 2:13–16). This reconciliation, wherein “the both” are created “one new humanity” (v. 15c),[2] is directly related to the nature of the church: “the both” are fellow citizens of God’s household that is growing into a holy temple in the Lord, being built together into a dwelling of God in the Spirit (vv. 19–22). The unequal-oneness is the trajectory application of the death of Jesus. Later, Paul calls the church to unity through the imagery of its “one baptism” (4:5). Paul associates baptism with Christ’s death: Or do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus have been baptized into His death? (Rom 6:3).[3] This is important, for Paul, then, links baptism to the nature of the gathered-church. The Colossian believers, Paul writes, have been buried with Christ “in baptism” (2:12a) and as a result, they are to set their minds on things above where Christ is seated at the right hand of God (3:1). This is directly related to the Colossian gathered-church’s identity: Do not lie to one another since the old man is laid aside with its practices and the new [man] is put on that is being renewed into the image according to the one who created it, where no Greek and Jew is, that is (kai) [where there is no] circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, freeman, but all things and in all is Messiah [my translation] (3:9-11). The setting is most certainly the deipnon (cf. 3:12–16) and the letter itself most assuredly was read at the after-meal symposium. Furthermore, in other passages Paul links baptism habitus to the associations within the gathered-church: For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:13). The gathered-church exists where unequals are present (and welcome) and there is no ethno-centric center of power. Furthermore, this cross/baptism-nature of church is applied to the gathered-church in Corinth regarding the Lord’s Supper and offers more support for a better reading of the Corinthian “table” issue (1 Cor 11). Paul links their baptism as a sign of their oneness (i.e., one body, 1 Cor 12:13a) and, then made trajectory application of whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit (v. 13b) to the issues experienced at the meal/table (i.e., the deipnon). Participation in the Lord’s Supper (the habitus) is itself to be proclamation of Messiah’s death (v. 26, For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until He comes), but was not so in the divisions made at the deipnon food habitus: . . . when gathering together as church, I hear that divisions exist among you . . . Therefore when gathering together, it is not to eat the Lord’s Supper [deipnon] (vv. 18, 20; my translation). [1] My italics to emphasize the inclusion of Samaritan (which is itself impacting) women being baptized. [2] NIV (2011). [3] See Rom 6:4: We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

0 Comments

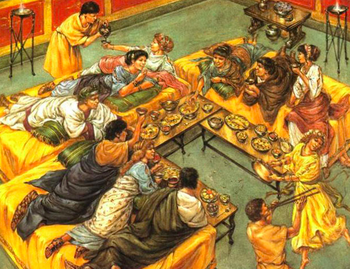

Leveling Habits: The Table, Household Baptism, and Kiss that Changed Everything (A) Doing “church” (and all its accompanying habitus) is a hermeneutic for reading the NT and for making church related application. Herein is our hermeneutical problem: NT documents tend to be read (heard) divorced from the most likely venue wherein they were originally read, heard, and repeated as instruction, that is, at a symposium after a gathered-church had reclined at a household deipnon (supper). NT documents should be read within such an authentic venue-hermeneutic, that is as a gathered-church set at a common meal (this is My body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of Me), the lifting of a cup to celebrate the Lord Jesus (this cup is the new covenant in My blood), and the ensuing symposium where instruction would have occurred. There is significant hermeneutical and interpretive value to the household-venue and, as such, is important for faithful and relevant trajectory application. A Meal and Table of Unequals. As most experience the Lord’s Supper, we find no NT equivalent nor within the first 150 years of church history. Despite the NT calling it a supper, most contemporary forms are foreign to the NT, that is, small crackers and a thimble-sized plastic cup (i.e., tokens of bread and wine), with congregants sitting in theater-like rows (i.e., pews or chairs), and all the action and authority “up-front.” The NT Lord’s Supper habitus centered on who reclined at table; whereas, most modern Lord’s Supper habitus is about the appropriate distribution of the tokens. Something happened at those NT/early church gatherings that was culturally subversive and sociologically seditious. The gathered-church formed its identity within the context of “household” amid habitus that was instructive to them and hermeneutical to us. In the Greco-Roman world, food occasions were a means for creating community and bonding that community together—meals were encoded, social habits were established, and status defined.[1] The habitus of each meal-gathering was a message “about different degrees of hierarchy, inclusion, exclusion, boundaries, and transactions across boundaries.”[2] Men were at the center of such meals and where one reclined at table indicated one’s ranking in society and among his associates. Invitation only. Women and slaves served and did not recline at table. Children were not permitted. However, it was acceptable at these meals for entertainment to include sexual encounters “between adult men and pubescent or adolescent boys.”[3] Depending on social class and wealth, there would have been plentiful entertainment, namely “flute girls, party games, gambling, dramas, mimes, strippers, jesters, moral poems, talks, debate, political, religious, moral, abusive, to erotic discussions”[4] and “sexual liaisons and promiscuities were very common.”[5] Classes did not ordinarily mix. The household banquet-meal was a built-in means for social formation, “a miniature reproduction of Roman society,” serving as a virtual classroom where one’s social status was taught, practiced, and formally enculturated. Social mapping was practiced, a habitus marking identity and social boundaries. The banquet-meal was the imperial instrument for maintaining “social control of the polis”[6] and was utilized “to dominate people and keep them in their place.”[7] This was interrupted by the household gathered-church where women, children, slaves, and men from differing classes and economic status were welcome to recline at table as equals—literally an open table of unequals. The gathered-church adapted, from its NT origin and as the early church took root in the ensuing century, the customary “pattern found throughout their world,”[8] the Greco-Roman household banquet-meal (deipnon) and symposium. Greco-Roman banquet-meal hosts and guests all acknowledged “the gift of food to the gods,” who were understood as the real hosts of the meal.[9] Such meal-gatherings always honored Caesar and some patron deity, which made such meals a blend of social and religious habitus. However, while Romans lifted a cup to Caesar and national deities, local gods, or a household emulate at the bridge between deipnon and symposium, Christians raised “the cup of blessing” in honor of Christ (1 Cor 10:16; cf. 11:23–28). This made each gathered-church at table seditious, for it was not only affirming a traitorous allegiance to another Lord and God, the occasion created a habitus that taught and maintained new identities, removed boundaries, and promoted counter- and cross-cultural relationships. However, the nature of the gospel and trajectory application of the cross brought about a challenging social-mapping: an ecclesial-demographical mapping of unequal people outside the banquet hall, yet who reclined as equals at table. Adapting the Greco-Roman evening deipnon/symposium set a household gathered-church on the eve (i.e., Saturday evening) of the Lord’s Day (i.e., Sunday), which accommodated the poor and slaves and working children that could not have attended an early morning “service,” for history had yet not giving us a 6-day work week with Sunday off.[10] The wealthy and upper-class church attenders had more power to adjust their daily schedule; the poor and destitute could not. Furthermore, this history and a household-venue hermeneutic allows a fair reading of the deipnon-table and Lord’s Supper issue in 1 Corinthians 10-11 to be about “haves” that were separating (or distinguishing) themselves through food habitus from the “have nots” at the Lord’s table. In this way, the gathered-church-temple (1 Cor 3:16–17; cf. Eph 2:18-22) was being destroyed (1 Cor 11:18–22). These meal-occasions failed, literally at table, to display love toward one another (the reason for chapter 13), thus they had ceased to eat the “Lord’s’ Supper,” abandoning the gospel-ecclesial social-mapping and habitus purpose of the meal.[11] [1] Lanuwabang Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement in Fellowship Meals: The Socio-historical Background of 1 Corinthians 11:17–34 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2016), 3; quoting Robertson Smith from his Religion of the Semites (page 217); —eating was understood as a sacred, mystical act when done together [2] Mary Douglas, “Deciphering a Meal,” in Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology (London: Routledge, 1975), 249–75, 249. [3] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 17; less so among Jewish households, but still drinking and other forms of merriment were very central to the latter, symposia, part of the banquet. [4] Ibid, 16. [5] Ibid, 17. [6] Street, Subversive Meals, 9. Italics original. [7] Ibid, 15. [8] Street, Subversive Meals, 11. [9] Jamir, Exclusion and Judgement, 15. [10] Ferment, 191; note: Justin, 1 Apol. 67.3; Origen, Hom. Luc. 38.6 [11] Street, Subversive Meals, 37; a similar venue-hermeneutic reading can be made of the James 2 “church” text. This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

Believing households and baptisms. The how seems irrelevant to Luke’s accounting, but the fact that believing households and baptisms are embedded into the story of the gospel spreading geo-demographically into the Gentile world should carry some hermeneutical and interpretive impact on our understanding of “church.” In Acts 2:41, Luke tells us that those who had received Peter’s explanation were baptized, indicating that “3,000 souls” were “added.” Most translations attempt a specific period of time.[1] However, the en (in) might very well lend the phrase (lit., in the day that) a figure of speech rather than a duration of time (i.e., 24 hours). Plus, “3,000” might be a cryptic reference to God’s judgment under Moses when 3,000 Israelites were struck down for their calf-idolatry (Exod 32:28). Three thousand would have been a “riot,” an unlawful assembly; and, all “3,000” hearing Peter, literally on one day (“on that day”) would have been near impossible. Luke is most likely summarizing and compacting the time and numbers. It would not, however, be a stretch to recognize Luke’s “added souls” (i.e., converts) and the reference to “baptism” over time (i.e., at the time of the Pentecost feast) rather than all at once (i.e., in that very day following Peter’s Pentecost sermon). It is not unreasonable to assume multiple baptisms, then, took place within the household-venues of those “added,”[2] for Luke’s narrative summarily and specifically put “conversions” and “baptism” in household venues (house to house, et al.). The “households” we are to imagine are not the modern, nuclear definition of family—a couple and dependent children within a home. Households of NT times were composed of far more than a simple, nuclear family. The household of the NT world we are to imagine was composed of a head of household male, his wife, grand-parents, children and later their spouses, children of household’s children (i.e., grand-children), other close relatives, slaves (indentured, bound, and free), as well as the wives[3] and children of the slaves. So, the narrative imagery of a household believing and/or baptism had a far reaching, cultural impact, and thus, for our understanding of “church.” Conversion stories abound in Acts, interestingly, most chosen by Luke are of societal outliers, those on the margins, foreigners, those deemed less than human (i.e., less than a male Roman citizen), Gentile military, or among the Jewish diaspora. Luke’s narrative choices are instructive and suggest an appropriate trajectory application of Acts 2. His choice for the first individual to believe is an Ethiopian Eunuch (8:26–39), a foreigner and unclean outsider. The first European convert is a lady, Lydia, where Luke indicates that she and her household had been baptized (16:15a); next a Roman jailer who was baptized, he and all his household (16:33; cf. 16:31)[4]; and, then as the gospel penetrated beyond Athens and into Corinth, we find Crispus, the leader of a diaspora synagogue that believed in the Lord with all his household[5] (18:8). Finally, Paul references his missionary/church-planting activities from house to house (20:20). Luke’s narrative choices and continual references to household “believing” and “baptisms” are a remarkable story-line that informs and forms how the gospel was “applied” as it spread into the Gentile world—and how we are to read “church.” It was primarily through households, of which some became the gathered-church venue for fellowship (the deipnon), worship, and instruction (the symposium), which very early on, as will be discussed below, was composed of believing households and baptisms that included women, children (both male and female), slaves, and, of course, men—of all ages and social status. The gathered-church in these households would have hosted the deipnon (i.e., common meal and Lord’s Supper) and the symposium that followed and, thus, contrary to the nature of Greco-Roman banquet-meal, unequals in society and culture would have been welcome, reclining, and cared for participants. This formed the nature of the gathered-church and its habitus. [1] E.g., that day, NASB, RSV; that same day, KJV; et al. [2] Though Luke certainly means “added to the number of believers,” what the “added” were added to is left unstated. We’d expect “added to the church” (and we tend to take it that way). However, the ambiguity is worth noting in that the concept of “church universal” has yet to develop and is actually absent in Luke’s accounting; what is present is church “in” a place with the emphasis on “house” as where believers met and instruction to place. This, then, would lend for the imagination to see the "added" being baptized within the “house to house” of gathered-believers. [3] Slaves had no legal means for marriage, so “wives” were female slaves attached or pledged to a male slave. [4] The Greek in v. 33 is simply “he and all his,” household being implied by Luke based on 16:31. [5] Baptism is assumed; cf. 18:8c This is a thread consisting of parts of a a recent paper presented at the 2017 Evangelical Theological Society's annual meeting in Providence, RI. The goal is to develop an anthology of essays (by various authors) on the subject, Christian Responses to Tyranny. Part 1 | Part 2a | Part 2b | Part 2c | Part 3 | Part 3a | Part 3b | Part 4a | Part 4b | Part 5 For the entire thread (remember to scroll backwards for previous posts) << Gathered-church >>

|

AuthorChip M. Anderson, advocate for biblical social action; pastor of an urban church plant in the Hill neighborhood of New Haven, CT; husband, father, author, former Greek & NT professor; and, 19 years involved with social action. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Pages |

More Pages |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed